R

E

V N

E

X

T

Nicolas Bourriaud, curator of the 16th Istanbul Biennial, began his press conference at the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University on September 10 with a scene from Werner Herzog’s 1982 film Fitzcarraldo, showing a giant steamship being hauled over a hill in the Amazon jungle. As Bourriaud explained, the promethean task in Herzog’s film mirrored the Biennial’s own last-minute migration from a former shipyard on the Haliç (Golden Horn)—due to an asbestos problem—to the newly constructed Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture near Istanbul’s other iconic waterway, the Bosphorus. Bourriaud added that the film, about a European colonialist whose plan to build an opera house in the Amazon is ultimately stymied by the locale, has additional resonances about the place of culture in relation to the environmental devastation of the Anthropocene.

The Biennial’s title, “The Seventh Continent,” refers to the swirling mass of plastic in the Pacific Ocean. For Bourriaud, the distinction between human and nature has collapsed in the environmental catastrophe we have wreaked on the Earth and on ourselves in the process of modernization. The plastic “seventh continent” represents, as he claims, the “massive and distant consequences of the ideology of ‘progress’ and of the industrial production and consumption society.” Through the Biennial, he was interested in looking at contemporary artists working with what he called “molecular anthropology”—those focusing on the “study of the effects, traces and marks left by human beings on the universe, and of their interactions with non-humans.”

“The Seventh Continent” is laid out as an essayistic narrative, along an intended path—a tediously prescriptive feature of several recent mega-exhibitions, including this year’s Aichi Triennale. The first work one encountered at the Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture was Dora Budor’s three chambers of glowing lights and dust, activated by sound sensors from the construction project nearby (“homeorhetic systems”); the sound frequencies become a score that turns the “dust chambers” to shades evocative of J.M.W. Turner’s dramatic seascapes and landscapes, which captured atmospheric pollution centuries ago. The next installation, Eloise Hawser’s The Tipping Hall (2019), comprises videos of a recycling plant, and metal objects reconstituted from the waste-management facility. New large works from Deniz Aktaş’s series of ink drawings, No Man’s Land (2018), depict landscapes covered in used tires. The following installation by Mariechen Danz, composed of 2,455 bricks imprinted with fossil-like models of human organs or bodies, and a funereal supine human figure splattered with multicolored paint, is where I began to notice how self-conscious many works in the Biennial appeared in their pseudo-ritualistic staging, which continued with works by Müge Yılmaz, Korakrit Arunanondchai, and Claudia Martínez Garay, among others. Bourriaud explained in the guide book that the original plan was to have two halves of the exhibition: one focused on environmental devastation, and the other on spirituality and alternative societies. But in its final form, the two were woven together.

The first time through the Biennial, I started on the fourth floor of the Museum, where Mika Rottenberg’s absurdly funny mash-up video Spaghetti Blockchain (2019)—featuring objects being burned, melted, and sprayed in some kind of testing facility cut with scenes of potato harvesting machines; the Large Hadron Collider; and Tuvan throat singers from Siberia—kept people enthralled, though it could also be flagged for exoticizing the latter. Next door was Güneş Terkol and Güçlü Öztekin’s WORLBMON (2019), a room-filling collaborative installation of their respective works on fabric and paper, and also a site for their band Ha Va Vu Zu to perform. Chang En-Man’s three-channel video, Ungrounding Land – Ljavek Trilogy (2018), one floor below, soberly addressed how indigenous groups in Kaohsiung are being displaced and marginalized by the Taiwanese city’s new developments.

The environment has been an important topic in Istanbul over the last decade, and one relatively safe arena where the country’s activists from the urban, educated, upper-middle class could forge links with farmers, fishermen, and artisans in an attempt to push back against the government’s strategy of breakneck development. In fact, the Museum sits at the entrance to a monstrosity known as Galataport, where cruise ships will soon dock and tourists will shop in Bosphorus-fronting malls. If the Biennial’s main agenda was to spark more conversation around the environment, then the multi-room installation by the Feral Atlas Collective was an embarrassingly weak attempt, with videos, illustrations, sound recordings, and short texts describing diverse instances of environmental devastation—none of which held particularly new information or was experientially engaging. In fact, artists in past editions of the Biennial have covered similar ground on many of these topics with far more rigor and more interesting presentations.

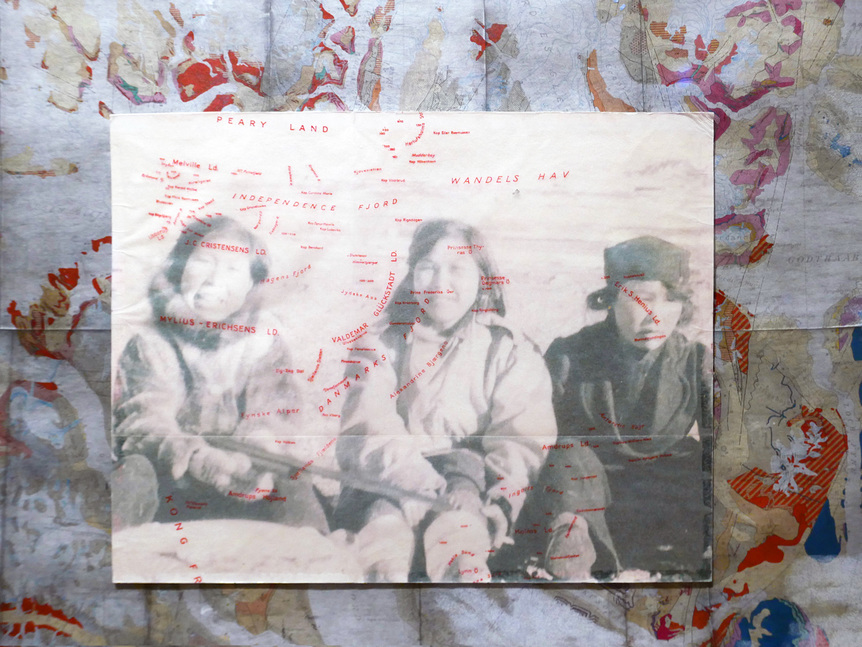

At the Pera Museum, I was only really engaged by the visual textures of Pia Arke’s collages Legend I-II-III-IV-V (1999)—made with maps and photographs of her Danish-Greenlandic family—and the strikingly life-like glass-blown forms of eels and other sea creatures in Charles Avery’s installation of a Scottish fish market. Simon Starling’s project of a Henry Moore sculpture replica that had been submerged in Lake Ontario and emerged bearing a coating of invasive mollusks, as well as Ernst Haeckel’s fin-de-siècle scientific drawings of sea creatures, echoed, in my mind, themes explored by artists in Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s 14th Istanbul Biennial, “Saltwater: A Theory of Thought Forms.”

On Büyükada, the strongest project was Hale Tenger’s Appearance (2019), which features a whispering voice projected from an abandoned stone mansion to its overgrown garden below, where the artist had placed circular disks of obsidian—the mystical black mirror—on the ground and on stands beneath the fruit trees. Glenn Ligon’s mini-exhibition at Mizzi Köşkü Mansion was based on James Baldwin’s time in Istanbul in the 1960s and early 1970s, and included a projection of Sedat Pakay’s moving short film following the African-American novelist around the city. Ligon’s own contributions were a large strand of red lights spelling out an upside-down “AMERICA” in the manner that mosques string up Ramadan messages between minarets; a pair of red-neon signs of politically charged dates in Turkish (March 31, 2019, the date of Turkey’s recent and disputed municipal elections; and October 29, 2023, the 100th anniversary of the Turkish Republic); and two videos of contemporary Taksim Square with jazz soundtracks. While I generally admire Ligon’s works (and Baldwin’s writing), this constellation bordered on the superficial.

What do those neon dates really mean, as a pair? And to the artist? As James Baldwin explains in Pakay’s film, while staying in Istanbul, he felt liberated from the racist politics of the United States, but also was not implicated in any of the historical ethnic violence in the region or contemporaneous state persecution. As the Kurdish novelist Yaşar Kemal allegedly replied to Baldwin’s perceived sense of freedom in Turkey, “Jimmy, that’s because you’re an American.” There seems to be more complexity here in the story of Baldwin’s time in Turkey than Ligon managed to explore in these works.

Throughout my experience of the Biennial, Bourriaud’s reference to Fitzcarraldo recurred to me. The absurd mania for money that led an opera-loving colonialist to enslave hundreds of indigenous people to drag a ship over a mountain in order to access a parcel of land with rubber trees is, of course, an appropriate allegory for the links between colonialism, environmental devastation, and the temples of high culture that the proceeds of exploitation pay for. But it is nonetheless a film in which only the white protagonist Fitzcarraldo has a real subjectivity, and the tragicomedy of the plot is experienced only through identification with this settler-colonialist figure, not with the reality of the local inhabitants. It felt to me as if Bourriaud’s perspective was similarly misaligned, with the dire urgencies of communities across the global south—from the Middle East to Africa, South Asia to the Pacific, the Caribbean to South America, which are already bearing the brunt of the climate crisis—largely unrepresented. Yes, the Anthropocene is global, but we are not all equally impacted, and perhaps for that reason, the Biennial seemed very un-radical in its response to the idea of a “crisis,” more conversational and hypothetical than practical or truly speculative about alternative realities and our collective future.

HG Masters is the deputy editor and deputy publisher of ArtAsiaPacific.

The 16th Istanbul Biennial is on view until November 10, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.