R

E

V N

E

X

T

Eminent American photographer Mary Ellen Mark (1940–2015), whose prolific career spanned five decades, passed away on May 25 at the age of 75, after suffering from myelodysplastic syndrome, a disease of the bone marrow.

As a young photographer in the early 1980s, Mark was one of several photographers whose work I took inspiration from. Among the large volume of works she has produced over the years, Ward 81 (1979) and Falkland Road: Prostitutes of Bombay (1981) stand out as some of the best photographic documentary works of our time. Her book, Photographs of Mother Teresa’s Missions of Charity in Calcutta: Untitled 39 (1985), spoke to me on a personal level and galvanized my decision in 1990 to work as a volunteer for 15 weeks at Nirmal Hriday, a home for the destitute and dying in Calcutta.

Ward 81 is a remarkable book that documents the lives of women who were held at the Oregon State Mental Institution in the late 1970s. There, she spent 36 days living in the ward, where she interviewed, photographed and established a bond with patients. Photographs of the patients’ daily routine were revealed with close intimacy—eating, bathing, sleeping, dancing, smoking, crying, or just staring blankly at a window or a wall were all captured through her lens with a compassionate eye. Intertwined together in one book, arresting moments of joy and pathos form a rare window into a world where few had access to.

Mark made her first trip to India in 1968, which became the first of several visits that took place over the next ten years. Witnessing the lives of prostitutes and the notorious conditions of the cage-like enclosures where they resided on Falkland Road, one of the most famous streets in the red light district of Bombay (now Mumbai), Mark felt the great need to relay what she had observed there to the outside world. The outcome of her project was published in Falkland Road: Prostitutes of Bombay.

For the first ten years of her visits to Falkland Road, she was met with much hostility. Women threw garbage and tossed water at her. Others pinched her and, in one instance, Mark was even hit in the face by a drunken man. Being the only Caucasian woman on Falkland Road, pacing up and down the same street all day long with a camera around her neck, crowds of men often gathered around her, either out of curiosity or to rob her. Needless to say, the situation was intimidating and shooting good photographs was almost an impossible task to achieve.

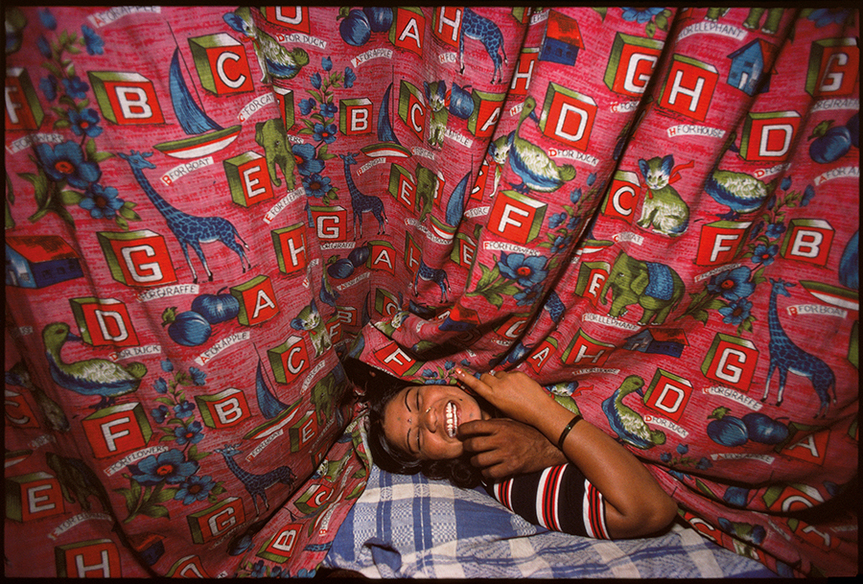

However, out of sheer perseverance, Mark returned to India in October 1978 and was finally rewarded with a breakthrough, after staying on Falkland Road for three months. At first, she started by befriending the street prostitutes, and then eventually moving into the brothels where madams and their girls worked and lived. Later on she befriended the other denizens of Falkland Road, who were the transvestites.

Falkland Road: Prostitutes of Bombay was Mark’s first book of color photographs, and it is a credit to her techniques and immaculate control of her lighting conditions in what would most certainly have been under-lit places. The richly saturated color in these photographs highlight the surreal living and working conditions of Falkland Road, deepening the pathos behind each gaze of the women there that Mark had befriended and photographed. Most strikingly, though, is the enormous trust that Mark built with her subjects. In return she was given extraordinary access to look intimately into all aspects of the women’s daily lives. Some photographs even captured the women while they were working, but always with a compassionate eye and a sense of humanity. The images do not appear salacious or voyeuristic; it merely emphasized the simple yet inescapable way of life that these women had to face everyday.

In 1979, soon after Falkland Road, Mark was commissioned by Life magazine to photograph Mother Teresa and her Missions of Charity in Calcutta, to coincide with the Nobel Peace Prize that was being awarded to her that year. Although she completed the assignment, Mark felt it was unfinished, and at times she felt uncomfortable and emotionally troubled photographing Nirmal Hriday, the home for the destitute and dying founded by Mother Teresa. Later, in 1981, she returned to India to complete what she has started.

On her second visit, Mark spent most of her time at Nirmal Hriday, but she also documented the other centers run by the Missions of Charity in and around Calcutta. The black-and-white images that resulted from this period demonstrate Mark’s straightforward and sensitive approach to her subjects, as was seen in Ward 81, allowing the subjects and the importance of the activities to take precedence over aesthetics. Many of the frames often showed hands in a comforting gesture on the patients, either from the sisters of the Mission, Mother Teresa herself or among the patients, as if to reinforce the underlying basic principle of the Mission itself—which was to provide healing through the simple act of caring. This body of work was first exhibited in 1983 at The Friends Gallery in Carmel, California, and subsequently published as Photographs of Mother Teresa’s Missions of Charity in Calcutta: Untitled 39 in 1985.

Meanwhile, also in 1983, Mark embarked on a story on runaway street children in Seattle, as part of another a commission for Life magazine. When the article was published, she went back to the streets of Seattle with Martin Bell, her husband and filmmaker, to make “Streetwise” (1984), an Oscar-nominated documentary film, which culminated in a book of the same title.

Throughout her rich and remarkable career, Mary Ellen Mark continued to work tirelessly, not only as a photographer, but also as a film producer, lecturer and educator, who led many workshops and lectures throughout the US. Mark published 18 books and received an impressive accolade of awards, including the 2014 Lifetime Achievement in Photography Award from the George Eastman House in New York, as well as the 2014 Outstanding Contribution Photography Award from the World Photography Organization, among many others. But above all else, she remains to me a quintessential humanist at heart.