R

E

V N

E

X

T

An invitation to view Ali Van’s work Express Labour (2017) feels akin to a spontaneous meeting at the apartment of an old acquaintance. I went and visited the exhibition a week after the work’s premiere and only performance, an event that was open to carefully selected guests—a mix of people from Van’s past and present, many of them coming together for the first time—who arrived without fully knowing what to expect. Set in New York City’s artist-run space Practice, the actual venue is located a few buildings away from the provided address—a decoy to avoid disturbing the neighbors, as one of the gallery’s co-founders explained as he escorted me up the stairs to the converted fifth-floor walk-up. Near Practice, which is located on a narrow street where Lower East Side meets Chinatown, small galleries co-mingle with a popular dumpling chain and Chinese hair salon filled with middle-aged women in curlers.

Van developed Express Labour between visits to her current home base in Hong Kong, where the artist grew up, and her birthplace in New York, during an unconventional one-month residency at Practice. The art space-cum-project, independently funded by Ho King Man, Cici Wu and Wang Xu, offers migratory artists one room with a cot and desk, and a studio that transforms into an exhibition space where their work will ultimately be shown at the end of their stay. A uniquely intimate experience with the artist often results.

Once inside, visitors logged their names using a bright red, vintage Olympia typewriter that belonged to Van’s mother. “It’s very satisfying,” I say aloud, firmly pressing down on the keys, as childhood memories come flooding back. “I don’t think I’ve used a typewriter since I was a kid.” The layering of the artist’s biography with the participant’s interactive experience corresponds with a line from Van’s invitation and offers a telling prelude: “A recollection unfolds, strange properties sometimes soft so close hairs harden like prop to attend new direction.”

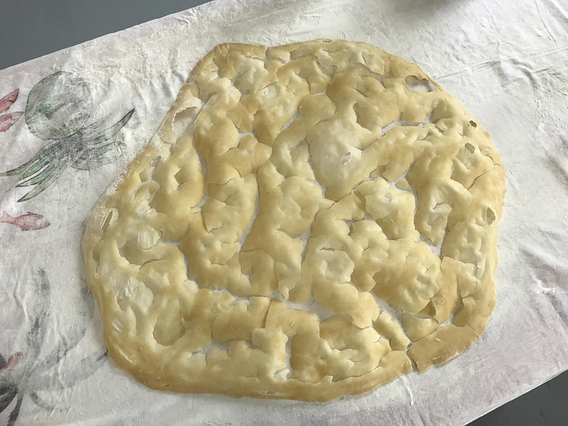

By the time I made my visit to Practice, the remnants of Van’s now week-old performance remained untouched, left behind as testaments to the show’s riddle-like subtitle, “A muse B ending C hair.” A cup of dried tea, which Van had prepared for a guest to drink, sat on the floor, alongside other ingredients and tools. A hardened piece of dough has cracked like a mosaic atop a table dusted with flour. And finally, a chair made of unfinished wood served as a functioning but shaky seat. Together, these artifacts formed a kind of “residual” exhibit.

A video documenting the event played in one corner of the room. Watching it, I observed Van in the center of the room. Her guests, some on the floor, others standing, form a reverent circle around her. Some have their iPhones out, recording her while she explains that she wanted to make furniture that “reconceives the body.” She begins to assemble the pre-cut legs and frame. Laughter ripples across the room when she struggles and asks the audience for assistance. Two people closest to Van work with her to try fitting the pieces into different holes. A man chimes in with his suggestions for what goes where. As they attempt various configurations, Van continues to narrate the process: “It’s like learning a language.” She asks the helper to hold the frame while she drills. “I don’t think I’m strong enough,” she says, flustered. More join in to help. At one point, she recognizes someone and says “hi” before drilling again. Her self-conscious laughter and heaving breaths can be heard throughout. Applause ensues when the chair is completed.

According to Cici Wu, Van’s work speaks to the “undiscovered potential of feminine sensibility,” and she deliberately chose tasks stereotypically associated with domesticity, such as the making and rolling of the dough. For the final part of her performance, Van brings the dough inside from the fire escape just outside of the window where it has been chilling. This time, she specifically asks for five volunteers to help stretch and pull the dough. “I haven’t lived a very human existence,” she says, first referencing her transient lifestyle in the past year, then adding, “ever since I came out of my mother.” Here, the video stops. When it starts again, she and the five volunteers begin coating the table in flour, their hands running everywhere. It is a collective effort.

The performance closes with Van hanging a reproduction of one of Picasso’s sketches, on loan from a guest in attendance. This roughly drawn model perhaps fulfills the figure of the muse that’s alluded to in the exhibit’s subtitle. But revisiting another line from the invitation, “when Olga gave Picasso her first milk”—a reference to the painter’s first wife, who was more châtelaine (housekeeper) than muse—I wonder if Van isn’t yet again drawing our attention to the forms of domestic labor that often go unseen. And by putting her step-by-step processes on display, and physically sharing the work with others, Van quietly revolutionizes her role as both a woman and an artist.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.