R

E

V N

E

X

T

In the pell-mell of China’s economic development, Wuzhen, a contemporary water town, is a leading player. It already hosts a drama festival, now based in architect Kris Yao’s elegant theatre that opened in 2013; a new museum dedicated to local writer and artist Mu Xin; as well as a lively children’s folk game festival. Noting the potential correlation of its own canal system to that of Venice, the Italian city that originated the world’s most renowned contemporary art biennial, the dreamy town recently inaugurated its own art exhibition, presenting extraordinary works often in unexpected places.

The exhibition of 40 local and international artists is divided into two parts: a beautifully restored former silk factory, which offers an uncluttered gallery environment, while significant works are also installed in six locations across the traditional town of Wuzhen. These sites bring about public interactivity and the pleasure that arises when seeing the old and the new come together.

In Wuzhen, however, you have to be careful; the town has fine-tuned its visitor experience so that it is hard to detect where true heritage ends and the directing of the hospitality industry begins. The interest of this exhibition, entitled “Utopias·Heterotopias,” lies in the way it bravely takes into account the context of Wuzhen’s contemporary culture, rather than endorse the town’s fantasy of presenting traditional authenticity to its visitors.Since the mid-1960s, China has seen history as an approach to the present rather than an account of the past; so, in Wuzhen, there is not much tension between the feigned history of tranquil munificence and marshaled visitor experience. In the exhibition’s 130 artworks, history is dramatized—where it is taken apart and reassembled to disclose its preconceptions—and also rebuilt and rerecorded. The threshold between space that is experienced and atmosphere that is felt, being in the past and in the present, is repeatedly evoked.

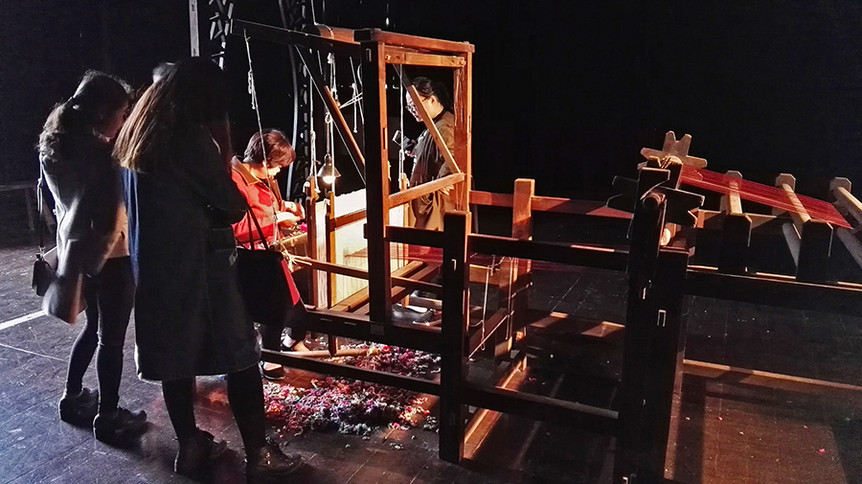

In American multimedia artist Ann Hamilton’s unquantifiable intervention, a theatre is changed into a silk loom. A bobbin occupies every seat and a weaver sits center stage. Barely visible, the silk filaments are held taught across the space, physically joining the weaver to every point in the auditorium. The spools of silk twitch imperceptibly as each weft incrementally builds the cloth. The effect is to make tangible a web that stands for the unique and diverse viewpoints and memories of the audience, with the different threads of their pasts drawing together. In the outside world, there is contemporary industry, a better solution that would manufacture a more uniform product, unpolluted by the bothersome thoughts that are knitted into this slow, hand-woven cloth. Like the manual laborers of the postindustrial period, the weaver in Hamilton’s work, a recruit from Wuzhen’s community, is caught in the cage-like structure of the loom. At the focal point of the theatre the weaver controls production, while dramatizing the way in which the weaver itself is produced as a subject. In Wuzhen the past is woven from many viewpoints, which is made clear by the exhibition.

“Art Wuzhen: Utopias·Heterotopias” is on view at the Wuzhen International Contemporary Art Exhibition until June 26, 2016.