R

E

V N

E

X

T

The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT9) was formulaic, rehashing a familiar, ethnographic approach of surveying artists from the Asia-Pacific region with little or no conceptual connection between the works or particularly insightful thematic underpinnings. Walking around the sprawling exhibition at the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) in Brisbane, one felt the atrophy particularly when encountering the woven baskets, handcrafted mats, knitted bags, money wheels and fish-trap-inspired exhibits from the Pacific that reified, with no self-awareness, the language of exoticization and fetishism seemingly inherent in Western ethnographic institutions, prompting one to ask the question: what has gone wrong?

Presenting diversity with nuance is no doubt a challenge. With this being said, however, there were unexpected moments of awe to be found between the disparate works. For the first time in the Triennial’s 25-year history, artists from Laos were included. Among them, Bounpaul Phothyzan’s Lie of the Land (2017), comprising repurposed, unexploded bomb casings placed in canoes with lush, living plants, powerfully reflects the violent past of the artist’s home country during the Vietnam War and the continued effects of the turmoil.

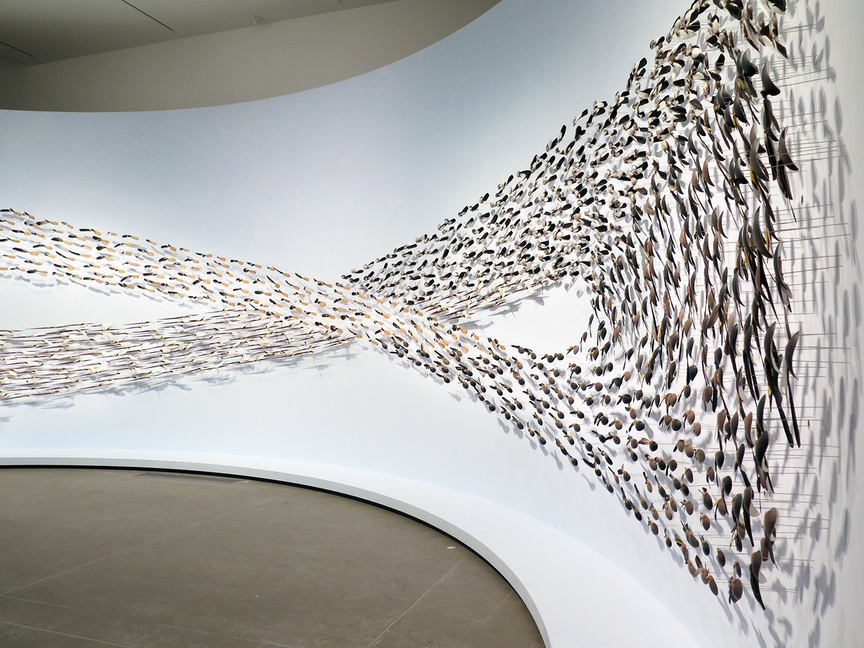

Other standout works included Jonathan Jones’ installation Untitled (Giran) (2018), of 2,000 sculptures with feathers and small tools, such as animal bones, emu egg shells and hardwood spear points, mounted on a wall to evoke a flock of birds in flight. The work’s audio component has voices from Indigenous communities whispering seductively about wind and country.

LISA REIHANA’s In Pursuit of Venus (Infected) (2015–18), a video projected across a 25-meter-wide screen, challenges the accepted historical narrative of the beginning of colonialism in the South Pacific.

Cao Fei and Lisa Reihana both delivered breathtaking videos. Cao’s 65-minute narrative Asia One (2018)—first shown earlier in 2018 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s “One Hand Clapping” exhibition—argued that artificial intelligence will increasingly take over the world. Reihana has already enjoyed global success with her video In Pursuit of Venus (Infected) (2015–17), which debuted at the 2017 Venice Biennale’s New Zealand Pavilion and toured to multiple locations before landing at APT9. The immersive, 25-meter work is admittedly an astonishing achievement. Reihana appropriates an 18th-century wallpaper purporting to show captain James Cook’s arrival in the Pacific Seas in 1770, illustrated by an artist who has never been to the islands, remediating the colonial depictions by inserting her own version of the meetings between Cook and the native residents.

Immense also describes Qiu Zhijie’s Map of Technological Ethics (2018), on the entrance wall of QAGOMA. Inspired by the medieval Mappa Mundi (a map dealing with philosophy rather than actual places), the latest addition to Qiu’s long-running series is contentious, with abortion and euthanasia featuring prominently.

More than half of the artists on view were women. Another highlight was the installation by Pannaphan Yodmanee titled Aftermath (2016), which resembles a building site where slabs of concrete and other detritus have been painted with delicate Buddhist-inspired miniature paintings.

Overall, APT9 lacked surprises. The re-examination of biennial and triennial customs and practices should now be a pressing issue. This has not escaped curator Zara Stanhope, who joined QAGOMA in 2017 with the task of putting together APT, and who said at our interview: “I would like to see it change. I think the gallery now is interested to do that.” Time will tell.

Michael Young is a contributing editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art is on view at the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, until April 28, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.