R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of “Fold: Golden Venture Paper Sculptures” at New York’s Museum of Chinese in America, New York, 2017. All images courtesy the artists and Museum of Chinese in America, unless otherwise stated. Photo by Ya Yun Teng.

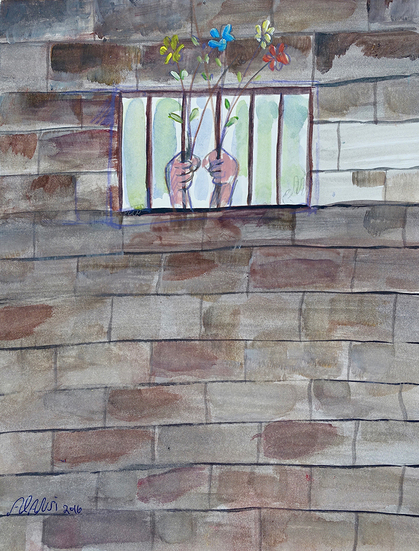

In the group show “Fold: Golden Venture Paper Sculptures” at New York’s Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA), which featured work by undocumented Chinese immigrants, a sculpture of an eagle locked in a cage provided an easily understood metaphor, its symbolism requiring no translation. Similarly constructed papier-mâché birds, free from any cages, stood nearby in contrast. The outstretched wings were made from a traditional Chinese folk art technique of paper folding known as zhezhi. No names accompanied the pieces. Our only introduction to their creators was through an archival video of men singing in Fujianese to the universally recognizable tune of Amazing Grace.

When MOCA first mounted the exhibition as “Fly to Freedom: The Art of the Golden Venture Refugees” in 1996, the artists behind the collection of paper sculptures were still being detained in the United States. They had arrived three years earlier, in a ship called Golden Venture that carried 286 passengers and had originated in Fujian, China. Upon sighting the shores of the US, however, the vessel had ran aground off the coast of Far Rockaway, Queens. Ten of the passengers drowned struggling to swim to dry land. Few escaped, making the surreptitious journey on foot and in the dark, disappearing into New York’s hustle, but most were apprehended by authorities and questioned, deported and detained. At the time of the MOCA show, the majority of the surviving passengers had already been sent back to China and other countries, but dozens remained in jail cells on US soil, awaiting a similar fate or, more optimistically, asylum in what they hoped would be their new home.

For 30 men who were held at York County Prison in York, Pennsylvania, art became a way not only to pass the time, but also to express gratitude to the pro-bono attorneys who had taken up their case. The asylum-seekers assembled these gifts using whatever materials they could find, from magazines to legal pads to toilet paper. Realizing how the artwork could further aid their cause, a grassroots activist group called the People of the Golden Vision helped collect and sell the pieces to raise funds for legal counsel and present the artworks as a means to plead asylum. Over the course of three years and eight months that the men spent behind bars, they crafted more than 10,000 sculptures. Dividing themselves into six groups, the incarcerated sculptors even cultivated a friendly spirit of competition that gave way to a whole new style of paper folding called qianzhi (colloquially known in English as “golden venture folding”), characterized by the use of modular designs to construct large representational objects.

In a timely commentary on immigration more than two decades later, the paper birds were on display again, reincarnated in MOCA’s latest exhibition. Alongside the various eagles, owl and two peacocks, other folded paper and papier-mâché objects offered a glimpse of versatility and creativity: surrealist hybrid animals, baskets, two cats fishing, lanterns, ships and boats, including a facsimile of the vessel that transported their makers. Seven-story pagodas reflect painstaking teamwork among the men, as the more skilled would teach and designate tasks to others in the group. They strove to make items that would be recognizable to their viewers and that referenced their own heritage. An example of this is the sculpture of a Statue of Liberty atop a dome modeled off the U.S. Capitol within Chinese city walls, illustrating how the artists married their cultural identity to emblems of American values.

From the poetry of Angel Island to art from Guantánamo, displays of artistry are often invoked as testaments of resilience, showing us that even in the most ugly of circumstances, people find a way to create something beautiful. In this sense, art can also serve as a powerful reminder of humanity, particularly when people are stripped of basic human rights. (Perhaps this is one reason why the US military has recently clamped down on the art permitted to leave Guantánamo Bay, to avoid inviting controversy and conversation about social control.) Back in 1996, the detainees at York were largely unable to speak out for themselves for fear of retribution from the Chinese government, as well as the Chinese crime syndicate responsible for smuggling the migrants thousands of miles across open sea. However, their sculptures helped galvanize local advocates and generate public sympathy, and because of this, they have remained on the radar. This outcome is already positive when compared to a group of women, also on the same ship, who were sent to a dentition facility in New Orleans, where they were mistreated by prison guards, denied medical care and subjected to solitary confinement. With no artwork to represent them, these immigrants have been rendered almost completely invisible.

Just as the detention of Chinese immigrants at Angel Island demonstrated the racial bias of the 1882 Chinese-exclusionary act, the Golden Venture incident drew public attention to the lack of due process for asylum-seekers under President Clinton’s administration. However, unlike the poetry on the walls of Angel Island’s buildings, which was undetected until 1970, the Golden Venture refugees’ artworks enacted real change for the creators. One could argue that the objects offered proof of the refugees’ humanity, contributing to their eventual release and parole by Clinton. Some earned special visas for their talents, while a handful received asylum. Frustratingly though, 15 of the formerly imprisoned individuals, who reside in the US today and who have raised children and grandchildren in the country, are still without a path to legal citizenship. Their ongoing story is just one of many that highlight a still-broken immigration system. When asked by the museum to be interviewed for a documentary film that accompanies “Fold,” several Golden Venture immigrants declined, citing concerns over shifts in immigration policy and enforcement since President Trump took office last year. In 2018, now afraid of the government of their adopted home, the artists continue to live in the shadows. Once again, their art must speak for them.

Mimi Wong is a New York desk editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

“Fold: Golden Venture Paper Sculptures” is on view at Museum of Chinese in America, New York, until March 25, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.