R

E

V N

E

X

T

The exterior of the Museum of Contemporary Art Busan, with AUGUSTIN MAURS’ I HAVE NO WORDS. For Propaganda Loudspeakers and Singing Voices (2018), and a banner by JAN SVENUNGSSON.

In recent years, South Korea’s second city Busan—known for its beaches, film festival, wriggling-fresh seafood and nightlife—has been endeavoring to establish itself on the national and regional art scene. The city has its own artist community and even an art fair since 2012. The municipality-sponsored Busan Biennale, now in its 11th edition, is a big part of the city’s cultural dynamic. In 2016, the Biennale took place in the Busan Museum of Art—which has a notable collection of modern and contemporary art from the region and is also home to the Lee Ufan-designed Space Lee Ufan—and F1963, a factory converted into a cultural space, where Seoul’s powerhouse Kukje Gallery has now set up an outpost. For the 2018 edition, the Biennale shifted its primary venue to the newly opened Museum of Contemporary Art Busan (MoCA Busan), located on the island of Eulsukdo, with a portion of the show unfolding at the former Bank of Korea building in the downtown area.

The 2018 Biennale was organized by artistic director Cristina Ricupero and curator Jörg Heiser. The duo had previously worked on the Nuit Blanche festival in Monaco, and had a limited time to pull the Biennale together after their positions were announced in February. They were supported by a team of advisers from Korea, including curators Manu Park and Beck Jee-sook, critic Youngwook Lee and artist Minouk Lim, with Gahee Park serving as guest curator for projects by younger artists from Asia—some of which proved to be among the Biennale’s best works. The Biennale’s other virtue was its clarity of subject, beginning with the title “Divided We Stand,” which inverts the familiar call for unity made by leaders throughout history including Syngman Rhee, South Korea’s first postwar president. The theme was also a tidy formulation for the situation today on the Korean peninsula, and other places around the world that remain partitioned or separated by the legacies of decolonization and Cold War politics that occurred after the end of the Second World War.

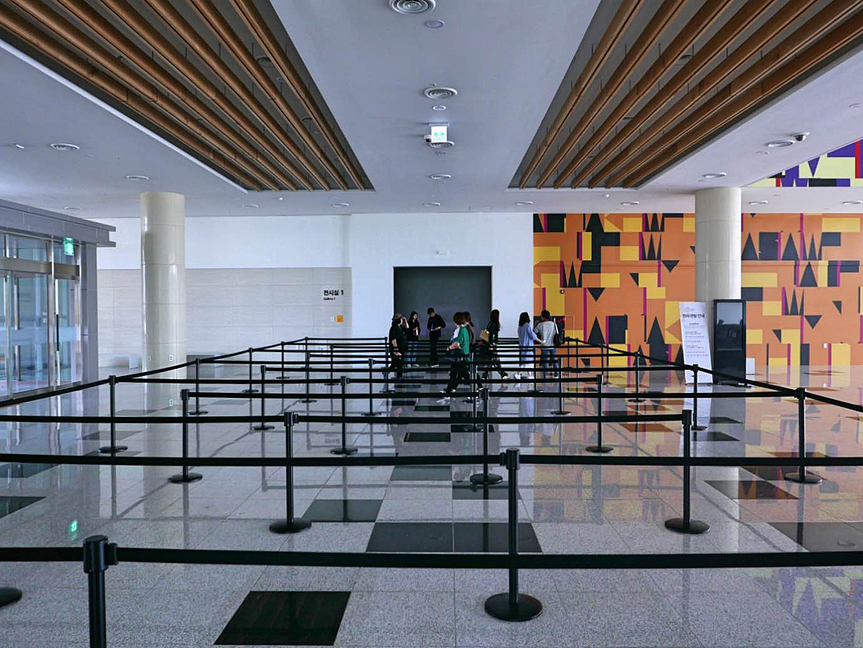

Borders, lines, fences, were all evoked in the lobby of MoCA Busan, where Eva Grubinger’s infuriating maze of black stanchions and nylon bands required guests to take a slow path to the border of the exhibition galleries. There, visitors were greeted with a projection of spot-lit train tracks appearing from the dark, the opening “hypnosis” sequence from Lars von Trier’s film Europa (1991), with a narrator inducing viewers to “go deeper and deeper” as the train, and the Biennale, proceeded into the nightmare of history. Turning right, Chin Cheng-Te’s collection of historical documents and press clippings, titled American Pie (2016), outlined Taiwan’s Cold War experience (including 38 years of martial law) and the influence of American military culture as the United States’ “Island Chain Strategy” was implemented on the nations of Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines as a bulwark against Chinese and Russian ambitions in the Pacific. Nearby, representing the other side of the First-Second World divide, was Chantal Akerman’s film D’Est (From the East) (1993), which portrays life in Poland and Russia just after the Soviet Union’s collapse through long, sobering takes, including many of people on the street. In a similar vein, Henrike Naumann—who was born in the former German Democratic Republic (East Germany)—presented an installation comprised of 1980s-Memphis-style postmodern furniture, a carpet shaped like post-reunification Germany, and TV monitors playing videos detailing the GDR’s disaffected youth culture during the post-Soviet era, which gave rise to the region’s budding neo-fascism today. The most powerful among the projects, in visual presentation and content, was Minouk Lim’s On Air (2017). The installation resembles the set of a television show—except the subjects are ghoulish mannequins and a taxidermy goat on a royal blue fabric stage, and the camera cranes are made from tree branches and old car headlights. It was accompanied by a new video, It’s a Name I Gave Myself (2018), with footage from the 1983 Korean television program Finding Dispersed Families, and a series of blacked-out signs relating to the ones the game-show participants wore, with question marks standing in for information about their early lives during the Korean War (1950–53) that they couldn’t remember. The themes of cultural loss, memorialization, the effects of military occupation and the cultural legacies of being on one side of the Iron Curtain or DMZ were strongly established from the outset.

Though the Biennale was thematically very coherent—perhaps too much so, for some viewers—my main criticism was the exhibition architecture and layout, which I found alternately awkward or unflattering in many places, with artworks either too close together or too far apart, which often offset the work’s impact (though brand new, MoCA Busan is not an architecturally distinguished building). Gabriel Lester’s The Conditioning (2018), for example, comprised a series of massive walls plastered with postwar propaganda imagery from around the world. They were intentionally clustered together near the entrances of the exhibition spaces in the museum’s lower level so that as viewers passed through them, no one country’s imagery predominated. But the drama of their size felt diminished by their being spread to the sides of the entrance foyer. In one place, though, the layout worked to an artist’s advantage. Walking toward a dim, seemingly unused corner to the left of the ground-floor level’s entrance, I nearly stepped on a pile of sand in the shape of a landmine, one half of Hayoun Kwon’s project about the DMZ, 489 Years (2016), along with an animation visualizing the experiences of a former professional soldier (called Mr. Kim) patrolling the heavily mined area. (The title is the amount of time it is estimated it will take to remove the millions of mines from the border strip.) The video (the piece has previously been shown as a virtual-reality work) is an absorbing account of a career spent performing dangerous, convert patrols inside this “demilitarized zone” that supposedly no one visits. Another project that used the space aptly was filmmaker Kelvin Kyung Kun Park’s ten-meter-wide, 17-minute single-channel video Army: 600,000 Portraits (2016), which offers a visually compelling portrait of the conformity that underlies Korean military life (and by implication, in a country where all the men must serve, all of society), as Park records new recruits performing their calisthenics and drills, and a whole theater of buzz-cut sporting, gray-uniformed boys are captured cheering and chanting for the female K-pop dancers performing on stage.

The routes to portray aspects of life in Korea’s other half are necessarily more circuitous. Oliver Laric’s project Mansudae Overseas Project (2013) consists of a one-meter-tall bronze sculpture of a standing man, made by Ri Sun Myong, an artist of merit at the Mansudae art studio in Pyongyang, based on Laric’s description that was passed to the studio via an intermediary. Also looking at North Korea’s export of its art production is Onejoon Che’s installation Mansudae Master Class (2012–16), which shows images and documents related to gifted or commissioned works located in 13 cities across Africa. A second project by Che, My Utopia (2018), is a video and stage set based on the real story of Monique Macias, the daughter of the first president of Equatorial Guinea who lived in exile in Pyongyang for 16 years after a military coup deposed her father, evoking the strangeness of her life there amid a largely closed and ethnically homogenous society.

The exhibition was wide-ranging in its geographical scope. Touching on Israel-Palestine was Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s video and sound installation Only the Beloved Keeps Our Secrets (2016), of footage recorded in occupied Palestine, and Smadar Dreyfus’s sound installation about families shouting greetings to each other from hilltops on Mother’s Day in the divided Syrian community of the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. Bani Abidi’s video Unforeseen Situation (2015) documents bizarre Guinness Book of World Record attempts in the Pakistani part of the partitioned Punjab province—including a man who attempts to crack more walnuts with this forehead than anyone else in history. Meanwhile, on the Indian side of Punjab, Amar Kanwar’s iconic film A Season Outside (1997) portrays the ritual of the changing guards at the Wagah-Atari border post. The Cold War era in China was represented in Liu Ding’s massive painting Temporary Actor B (2015), a large painting of Social Realist-looking public sculptures dating from the late 1970s and early ’80s, while perhaps more intriguing is Zhang Peili’s installation Scenic Spot Open Temporarily (2018), a wall of stacked newspapers in front of which is a small wooden platform that visitors can stand on to try to peer over the wall. (Zhang performs periodically, hand-tearing newspapers on the other side, just out of sight). Khaled Barakeh’s project The Shake – Materialising the Distance (2013–18) is a cast of the space between two hands of two figures in a public sculpture in Derry/Londonderry, Northern Ireland.

The Bank of Korea was a scrappier exhibition venue. I recoiled at the Jean-Luc Blanc large painting of a middle-aged man’s face whose eyes are, per the oxymoronic but accurate description in the catalogue, “highlighted by a white bright shadow,” meant to evoke George Orwell’s “Big Brother.” On the ground floor, the Cold War’s surveillance infrastructure was portrayed in an 1997 installation by Jane and Louise Wilson, Stasi City, shot by the artists in a wire-tapping bureau operated by the East German secret police. Im Youngzoo’s newly produced, essayistic video Guest Star (2018) merges narratives about misunderstandings, through the motif of a supernova (the death, not the birth, of a star), the 1963 message “the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog,” sent by the US to the Soviet Union to test the keyboard on the new joint hotline, which prompted the Kremlin to hire cryptographers to decipher its meaning, and a lip-reader trying to decide footage of leaders’ conversation at the recent North-South Korean summit in April 2018. Like Blanc’s painting, the sculpture of a gigantic, dead-looking black crow by Laura Lima and Zé Carlos Garcia repelled me with its gratuitous messaging, as did Dora Longo Bahia’s two paintings in reds and oranges of abandoned-looking amusement parks, scribbled with the names “Fukushima” and “Chernobyl.”

I preferred the moments of the show when things became more occult or speculative, such as Oscar Chan Yi Long’s maximalist wall paintings in ink and hanging banners of crazed-looking animals and skeletons, Suzanne Treister’s tarot cards and detailed conspiratorial mind-map drawings from her “Hexen 2.0” series (2009–11), and Wanuri Kahiu’s Afrofuturist video Pumzi (2009), about a museum curator who braves the earth’s post-apocalyptic climate to plant a tree. Musician Minwhee Lee and artist Yun Choi’s collaborative music videos Viral Lingua (2018) were inspired by vestiges of Cold War ideology in contemporary society, and depicted a woman whose eyes are painted like two sunsets, standing in front of a setting sun while crying about leaving her country. The biennale’s last work, on the top floor, at the end of the corridor, was Phil Collins’s Delete Beach (2016), a room-sized installation of mounds of sand, oil drums, tires and bubbling pits of black liquid, with electronic music by Mica Levi and an anime created by the Japanese company Studio 4°C about a schoolgirl who joins an anti-capitalist resistance group. From its very literal beginnings about borders, divided territories and communities, the Busan Biennale ended with a vision of the earth’s collective post-carbon future—one where all the countries of the world seem to be united in failure.

HG Masters is the editor-at-large of ArtAsiaPacific.

The 2018 Busan Biennale, “Divided We Stand,” is on view until November 11, 2018.

A full review will be published in the forthcoming November/December issue.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.