R

E

V N

E

X

T

REETU SATTAR, Harano Sur (Lost Tune), 2016, documentation of performance at Dhaka Art Summit, 2018. Photo by Pablo Bartholomew. Courtesy Dhaka Art Summit.

As I walked towards the historic Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy bright and early on February 4, I was confronted by a chorus of musicians on harmoniums and the steady low hum emanating from their instruments. I was fortunate to have made it just in time for Reetu Sattar’s performance-based work, Harano Sur (Lost Tune) (2016), a highlight for many at the fourth Dhaka Art Summit (DAS) that recalled the sounds once integral to everyday traditions in Bangladesh, now lost to modernity.

Building on this welcome in the foyer of Shilpakala, the Summit’s main venue, were 12 mural panels—originally part of a set of 13, with the last component acknowledged as irreparably damaged—of a forgotten work from 1972 by the short-lived collective Oti Shamprotik Amra (We, the Contemporary). The mural, unearthed by chief curator Diana Campbell Betancourt from the Chittagong University Museum, depicted sentiments that informed the founding of Bangladesh, including memories of the Liberation War of 1971, the emaciated peasantry that have become synonymous with it, as well as the syncretic secularism that was important to the movement. Most significantly, the artist group behind the work was responsible for the first international exhibition of art from Bangladesh. The mural thus emblematizes a desire to prioritize the arts and an internationalism within it—a thought which was also part of the founding agenda behind Shilpakala Academy in 1974.

Installation view of “Bearing Points” at Dhaka Art Summit, 2018. Photo by Pablo Bartholomew. Courtesy Dhaka Art Summit.

This drive for internationalism, woven in the fabric of the arts during the early years of the founding of the nation of Bangladesh when it was still attempting to find economic and political footing, is further elucidated in the exhibition “Asian Art Biennial in Context,” one of ten being presented as part of the Summit. Through a retroactive glance at works from the first four editions of the Asian Art Biennial—the oldest surviving biennial in Asia, based in Bangladesh—that have been in the collection of the Shilpakala Academy all these years, along with archival materials from Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, a legacy of patronage and precedent for global exchange was made apparent. DAS was thereby firmly rooted within the art historical narrative of the region.

The pertinence of art and international camaraderie in times when such initiatives could have been presumed to be unlikely was further supplemented by Vali Mahlouji’s delightful exhibition, “A Utopian Stage.” This re-presented material from the exhibition archives of the Festival of Arts, which took place in Shiraz-Persepolis from 1967 to ’77. I would learn that the event was an extraordinary modernist initiative that foregrounded narratives from post-colonial contexts during a decade of global crises, leading a vanguard of universalist attitudes. This against-all-odds consciousness reminded not just Bangladesh but also the rest of the world of the importance of biennials and cultural initiatives, a concept that is still relevant today when there are comparable geopolitical configurations, validating events such as DAS. That there has been recent curatorial focus on South Asian narratives in events across the region—despite limited access between countries in the sub-continent due to stringent visa regulations and shipping hassles—only further supports the overall artistic direction of the Summit.

This emphasis on region was opened up to criticism in the rest of the event, parts of which contemplated issues of liminal nationalities, marginalized identities within the nation state and migratory populations. For example, the persecution of the Rohingya community in Myanmar and their exodus to Bangladesh was acknowledged in Betancourt’s exhibition “Bearing Points.” Jakkai Siributr’s The Outlaw’s Flag (2017), displayed as part of the showcase, was a powerful testament to this international crisis. The artist created flags for imaginary nations from the debris found along the shores of Sittwe in Myanmar, from where the refugees fled, and from Ranong in Thailand, where they arrived, highlighting the Buddhist-Muslim tensions in the two countries. From Raqib Shaw’s dream-like treatise on cosmopolitanism to Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran’s deities in drag, and the intimate text-based work, Impossibility of Loving a Stone (2017) by Omer Wasim and Saira Sheikh, “Bearing Points” seemed to have been purposefully conceptualized to diverge and expand on the curator’s notes rather than converge towards it.

This was in contrast to Devika Singh’s exhibition “Planetary Planning”—which was no less successful—where artworks seamlessly reinforced each other. In this relatively small project, compared to the rest of the exhibitions at DAS ’18, it was impossible to pick favorites. Yet, it would be criminal to write any account of DAS without mention of Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi’s unrealized proposal for a memorial to Gandhi. The form of the monument, imagined as the “outstretched hand of humanity,” bears the traces of Noguchi’s travels through India and the influence this had on his practice.

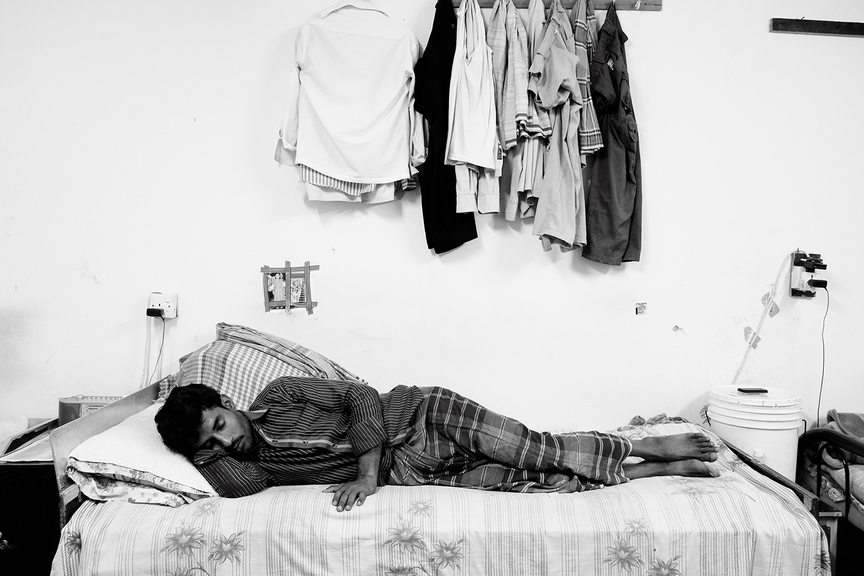

On the other hand, Cosmin Costinas prompted his viewers to think about the historical connections and postcolonial narratives that run through Bengal and Southeast Asia in his exhibition. The show seemed to stack one work against another, giving visitors the feeling of having walked into a curiosity shop. Its anchor was Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Chai Siri’s film installation, an uncharacteristically austere work among the other exhibits, which discussed the over one million Bangladeshi immigrant workers in the United Arab Emirates. This focus on communities extends to the programming around DAS, such as in Sovereign Words, which aimed to bring together artists, poets, storytellers, performers, curators and scholars of indigenous communities from around the world. It almost made me wish I had travelled to Dhaka later in order to be able to catch it.

For “One Hundred Thousand Small Tales”—the only exhibition to focus on a particular country’s artistic production outside of Bangladesh—curator Sharmini Perera brought together seminal works of art from Sri Lanka, charting the radicalism evident throughout the island’s art history, where such historicizing attempts have been rare. Within the exhibition, Anoli Perera’s I Let my Hair Loose: Protest Series III (2010–11), placed next to TPG Amarajeewa’s Do not Measure Me (2001) was a particularly striking juxtaposition. Both photo-based works subverted the posturing and anthropological connotations of photography from the colonial era, from the vantage point of Perera’s female, and Amarajeewa’s male bodies.

Despite an edition of the Dhaka Art Summit that was consistently in dialogue with historical and contemporary narratives from Bangladesh, there was very little that took the viewer outside of the venue of Shilpakala. This perhaps would have been a logistical nightmare, given the infamous traffic and chaos of Dhaka’s streets. Yet, it reminded me that not all art needs to be public to engage with the work’s context and to produce generative conversation—the steady stream of local residents pouring in to the Summit was evidence of this. Perhaps, I could play devil’s advocate and argue that certain kinds of conversation can only take place within closed walls in contexts such as South Asia, faced with censorship and inflammatory sentiments. But this is another essay altogether.

The fourth edition of Dhaka Art Summit was held from February 2 to 10, 2018, at the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy, Dhaka.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.