R

E

V N

E

X

T

At the beginning of the 20th century, American photographer Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868–1952) embarked on one of the most ambitious projects ever attempted by anyone in the history of photography: to document and “find the spiritual essence of North American Indian civilization,” at a point in time where it was fast disappearing. Fortunately, for the first time in Hong Kong, art enthusiasts will have the opportunity to view 24 original photogravures from Curtis’s masterwork “The North American Indian” (1907–1930) at the Empty Gallery, in an exhibit titled “The Man Who Sleeps on His Breath.”

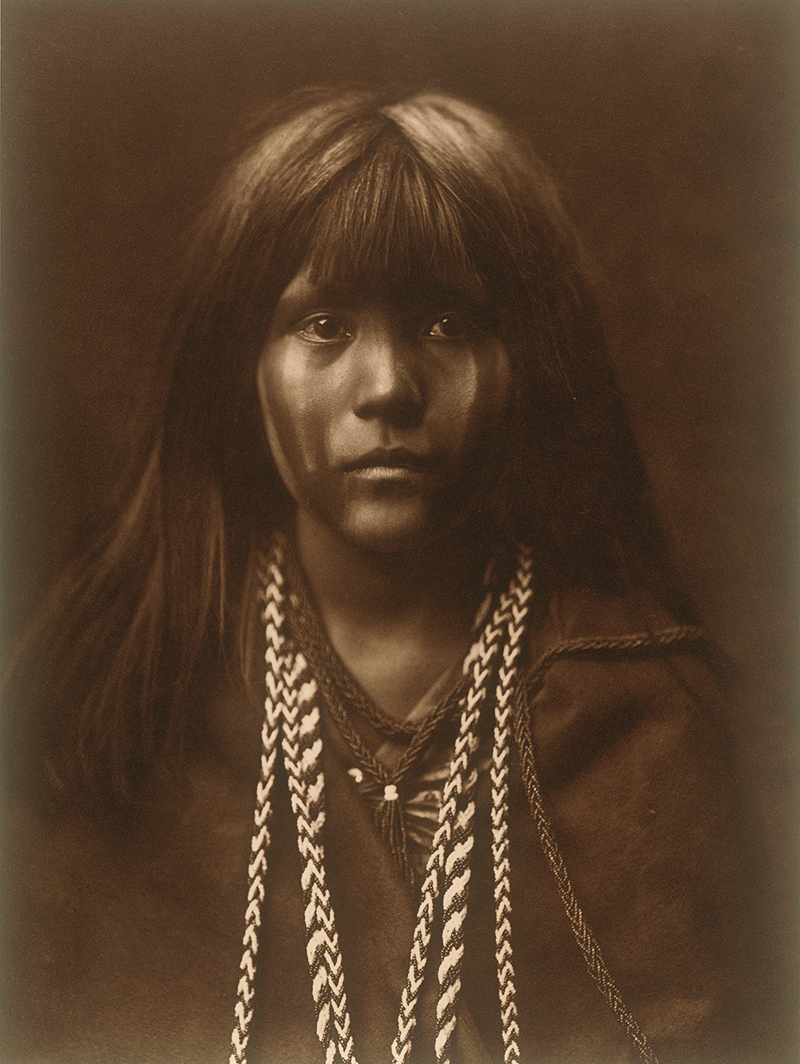

Tucked in the heart of southern Hong Kong Island, the Empty Gallery opened in March 2015 and provides a unique environment for art viewing. Founded by Stephen Cheng (a Curtis enthusiast), the entire gallery is covered in black, requiring a few minutes of acclimatization upon entering. As one emerges from a short corridor into the exhibition space, the first portrait, Mosa-Mohave (1903), appears dramatically under a small focused light source illuminating only as far as the edge of the photogravure, while giving the image a warm, even glow. Playing overhead is an original soundscape composed by Italian electro-acoustic musician Valerio Tricoli, commissioned specifically by the gallery to accompany this exhibit, which offers an extra haunting element to the viewing experience.

Born in Wisconsin in 1868, Curtis took to photography at an early age. When he was 12 years old, Curtis recycled a camera lens his father, a chaplain and private in the Union Army, had brought home 15 years earlier. Using parts he bought for USD 1.25 and instructions from the American periodical Wilson’s Photographics, Curtis built his own crude camera. Embarking on his career, at age 17, Curtis landed a job as an apprentice photographer in Minnesota. Two years later, his family moved to Seattle, and there Curtis married and established his own portrait studio. In 1895 Curtis took his first portrait of a Native American, that of Princess Angeline, the eldest daughter of Chief Sealth of the Duwamish tribe.

Yet it was a chance meeting in 1898, while mountain-climbing on Mount Rainier in the Pacific Northwest, that set Curtis on the path away from his studio and family. Curtis befriended George Bird Grinnell, anthropologist and founder of Audubon Society and an expert on Native American cultures. Their newfound friendship led to an invitation to join the Edward Henry Harriman expedition to Alaska in 1899, and for Curtis to accompany Grinnell out to Montana in 1900 to observe and photograph the Piegan Blackfeet tribe. In Montana, Curtis became deeply affected by what he saw and, under Grinnell’s tutelage and encouragement to do a grand project on the Native American Indians, Curtis began what would become an all-consuming, obsessive project to document more than 80 tribes through photographs and recordings of their songs.

His photographs of the Piegan people became known for their sheer beauty through his popular exhibition sponsored by the National Geographic Society, as well as various published magazine articles and lectures, which he gave at a number of institutions across the country. In 1904 his work caught the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt who subsequently commissioned Curtis to photograph his daughter’s wedding and other family portraits.

Five years into the project, with his own funds exhausted, Curtis sought the patronage of John Pierpont Morgan, financier and railroad tycoon. Morgan sponsored Curtis with a grant of USD 75,000 paid over five years, in exchange for 25 sets of volumes and 500 original prints. With a trail wagon and assistants traveling ahead to arrange visits, Curtis set out on a journey that would see him photograph some of the most important Native Americans and tribal leaders of the time.

Tribal elders found him amusing would drag around his 14-by-17-inch view camera with glass-plate negatives to photograph them, which allowed him to yield the crisply detailed gold tone prints he was known for. The Native Americans came to trust him over time, and sometimes for a fee would agree to organize reenactments of battles and traditional ceremonies for the keen photographer. They even named Curtis the “Shadow Catcher.”

However, luck was not on his side for long. Morgan died unexpectedly in Egypt in 1913, and although JP Morgan Jr. pledged continuing support of Curtis’ project, albeit in much smaller sums, the photographer was forced to raise additional funds by producing In the Land of the Head Hunters (1914), the first silent, feature-length film to have a cast composed entirely of Native Americans. Sadly, the endeavor flopped financially and Curtis lost his USD 75,000 funding. He then took up work in Hollywood, where his friend Cecil B. DeMille hired him as a cameraman for The Ten Commandments (1923). Curtis continued to struggle financially and had to sell the rights to In the Land to the American Museum of Natural History for a mere USD 1,500. Nonetheless, he was not one to be defeated. His desire to finish the remaining volumes of his photographs drove Curtis to agree upon a deal with the Morgan Company: Curtis relinquished his copyright on the images for “The North American Indian” in exchange for financial support to complete his project.

After the First World War, the public had long ceased caring about Native American culture, and by the late 1920s, Curtis was alarmed to find the tribes he visited had been devastatingly affected by forced relocation and assimilation. Curtis finished “The Native American Indian” within months of the start of the Great Depression in 1929, but the stock market crash made it nearly impossible for him to sell any of his work. After taking over 40,000 pictures over 30 years, the last of his planned 20-volume set was published in 1930, but to barely any fanfare. Upon returning to Seattle, Curtis suffered a complete mental and physical breakdown, a failed marriage, a broken family and loss of finances. In the end, he died of a heart attack in Los Angeles in 1952. Further adding to the tragedy, the Morgan Company eventually sold 19 complete bound sets of “The North American Indian,” along with 200,000 of Curtis’s photogravures, to the Charles Lauriat bookstore in Boston for a mere USD 1,000.

In retrospect, what is all the more remarkable about Curtis’s achievements was that it occurred at a point when photography was still in its infancy, when few photographers had ventured beyond the realm of their studios. Curtis had been onto something from the start; he knew he was in a desperate race against time to document the rapidly vanishing way of life of the North American Indians. The importance of his work, both as a photographer and as an ethnographer, continues to be an inspiration for what one person can do. It gives us an image of a time during one of the most violent upheavals in American history—one that would have been lost forever if not for Curtis’s vision, his unending obsession, and his deep love and personal bond with the ceremonies, culture and beauty of the Native Americans. At his pivotal first meeting with JP Morgan in 1906, the financier praised Curtis thusly: “Mr. Curtis, I admire a man who attempts the impossible!”

Billy Kung is photo editor at ArtAsiaPacific.