R

E

V N

E

X

T

A year after Germany had its milestone exhibition of Chinese contemporary art, “Die 8 der Wege” (“The 8 of ways”) in 2014, a new, widely-promoted show on the same subject opened its (many) doors in May, in Germany’s North-Rhine Westphalia state. “China 8,” organized by the Stiftung für Kunst und Kultur e.V. Bonn, takes place in not one, but nine museums throughout the Ruhr valley, Germany’s former industrial region. Each of the participating institutions has curated its own distinct exhibition, organized by medium. The exhibitions include “New Figuration – Narrative Sculpture” (at Duisburg’s Lehmbruck Museum) and “Arrested Time – Video and Sound Art” (at the Skulpturenmuseum Glaskasten, in Marl), as well as an overview of the entire endeavor hosted by Düsseldorf’s NRW-Forum. In total, 500 works by 120 artists are presented across various media practices, including contemporary ink, photography, painting, sculpture, installation and video art.

In with the . . . Old?

As a state capital and institutional epicenter, Düsseldorf’s NRW-Forum takes a wide-angle lens with “China 8 Overview – Views of China,” showing works by 36 of the artists who are participating across the “China 8” institutions. The NRW-Forum exhibition opens with Bending (2010), one of Yue Mingjun’s frantically laughing steel sculptures that can be found crouching at several other participating museum entrances. Inside, the exhibition space is crowded with works by China’s art-stars, including painter Ding Yi, video artist Hu Jieming and animator Miao Xiaochun—evidence that curators and art institutions in Germany still rely on established Chinese artists that have dominated the art market since the 1990s.

In particular, the “China 8” project’s painting category suffers from an acute dependency on contemporary Chinese artists seemingly plucked from Sotheby’s Spring auction catalogue. In “The Vocabulary of the Visible World – Painting," held at Duisburg’s Museum Küppersmühle for Modern Art, Fujian-born Wang Guangle’s structured Coffin Paint canvases (2004– ) and Zeng Fanzhi’s large-scale canvases, Hare and Head of an Old Man (both 2012), are displayed adjacent to key works by big-name artists such as Zhang Huan, Zhang Enli and Zhang Xiaogang.

Only the Kunsthalle Recklinghausen, with “The Panorama of Painting – Emerging and Established Positions,” offers an array of young, dynamic contemporary thinkers who specialize in the medium. For example, Han Feng’s transparent color palette illuminates odd perspectives of manmade infrastructures that pervade everyday life. His shades of black, grey and pale rose transform quotidian views into ephemeral acrylic drawings. Sichuan Fine Arts Institute graduate Li Qing’s saturated, non-narrative architectural depictions relate to her fragmented childhood memories of the late 1980s and ’90s.

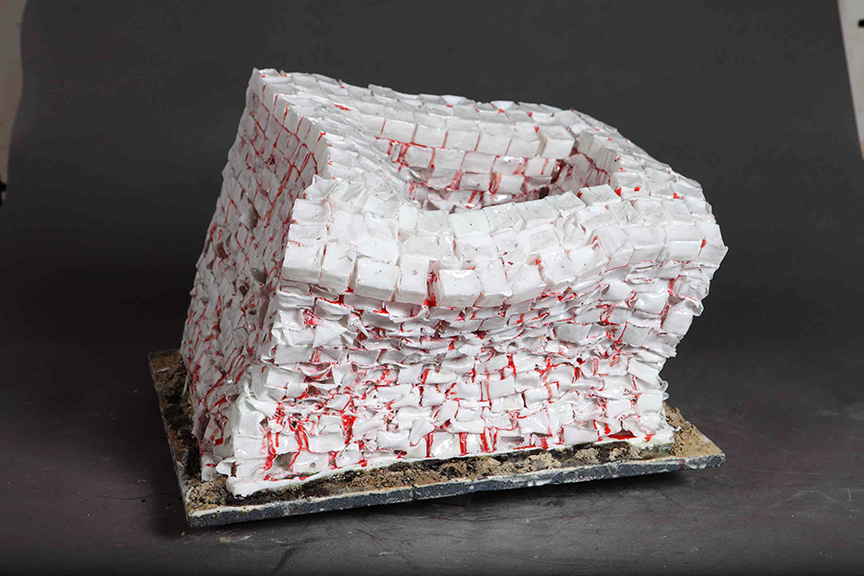

Back in Duisburg, at the Lehmbruck Museum, contemporary sculpture and installation works include heavyweights Fang Lijun’s fragile ceramic ruins and Xiang Jing’s sculptural manifestations of disillusionment. Although “New Figuration – Narrative Sculpture,” like its sister shows, centers on celebrity artists (for example, Xu Bing), some lesser-known participants are also included. Multidisciplinary artist Jiang Jie fascinates with atmospheric, room-filling works such as Pink Utopia (2009–10), a silk-bag and tile installation meticulously reconstructed on-site at the far end of the exhibition.

Surprises and Shortcomings

The art museums of Mühlheim an der Ruhr and Hagen—two small cities often overlooked by visitors to West Germany—surprise visitors with their lineups of installations and sculptures in “Models of Irritation – Installation and Sculpture” and “Paradigms of Art – Installation and Object Art,” respectively. Works range from acclaimed artist-couple Yin Xiuzhen and Song Dong’s colossal metal Chopsticks 2006 (2006) to newcomer Adrian Wong’s Bauhaus-like Telepathically-Designed Bespoke Rabbit Warrens I/II (2014). A former student of psychology and sculpture, Wong presents two small constructions based on research on animal telepathy, which seemingly follow the mantra of “form follows function.” Also at Osthaus Museum Hagen are the signature birdcages of Kum Chi Keung, whose decade-long practice of shaping confined spaces out of bamboo references Hong Kong’s increasingly claustrophobic urban cluster.

While some of the participating museums feature a complementary selection of works, the museum in Gelsenkirchen’s “Tradition Today – Chinese Ink Painting and Calligraphy” falls short. In comparison to its opening artwork, a mind map of cultural and philosophical history by prominent ink artist Qiu Zhijie, like-minded pieces by younger artists such as 27-year old Frank Tang or Beijing-based Sun Xun do not match up to its standards. Yet there is one work that makes one’s visit to Gelsenkirchen worthwhile: Rising Mist (2014), a video work by 35-year-old Shanghai-based artist Yang Yongliang that plays on four hanging scroll-sized screens. It depicts a mountainous landscape that, upon closer examination, reveals to contain moving images of a contemporary metropolis complemented by sounds of actual city bustle. Yang’s refined skills, developed during his studies in both traditional ink and visual art, are a treat for the viewers’ senses.

Brave New (Media) World

Across several venues, the “China 8” project’s abundance of new-media works does not disappoint in terms of scope or content. Essen’s Folkwang Museum displays an outstanding array in “Works in Progress – Photography from China.” Visitors enter through artist collective MA DAHA’s absurd installation Everything that Exists is a Thought in the Mind of MA DAHA (2015), a Dadaist-collage-like amalgamation of social-media images. Opposite Mo Yi’s pixelated Mao print We Wish Our Red Sun Long Life (2015) hang Beijing-based Du Yanfang’s intricate Dreaming Back Homeland works (2013) based on her childhood memories of growing up in rural China. Colorful figure drawings superimposed on landscape images oscillate between childish imagination and factual documentation of the countryside.

In Marl, the artists featured in its vast video-art section awkwardly spans generations born during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) to that of recent art-school graduates. Zhang Peili, the father of Chinese video art, is represented by one of his sequence works, Happiness (2006), in which two films enter into a dialogue of banal scenes that are met with delirious applause. From the younger generation, Fang Lu showcases her comprehensive multi-screen work Lovers Are Artists Part 1: Amorous Acts (2012), comprising utterly bewildering performances in Beijing’s old town—such as using pancakes instead of chalk-drawn patterns for a game of hopscotch.

“China 8” has been openly criticized for casting too wide a net of old and new faces, all under the name of contemporary Chinese art. Yet it has also welcomed a large number of emerging artists—especially throughout the new-media sections—to the international museum landscape, leaving seasoned art-lovers hoping that “China 8” could be a stepping stone toward new approaches in curating Chinese contemporary art in Germany.

“China 8” is on view in Germany’s Ruhr region until September 13, 2015 with the exception of “China 8 Overview – Views of China,” at NRW-Forum Düsseldorf, which closes on August 30, 2015.