R

E

V N

E

X

T

March Meeting 2018 aimed to discuss the ways in which artists, curators and other practitioners use the forms of organizations or institutional spaces as modes of resistance. In the very first session, ABIR SAKSOUK (pictured far left), an architect at Public Works in Beirut, explained her various projects at the firm, including one which sought to preserve public play areas for children. Also pictured (left to right): curator ZEYNOP ÖZ, moderator of the panel; SHARMINI PEREIRA of the Sri Lanka-based, non-profit publisher Raking Leaves; ALPER TURAN, co-founder of Istanbul’s independent initiative DAS Art Project. All images by Ysabelle Cheung for ArtAsiaPacific.

In times as troubling as ours, how do we organize strategies for survival and resistance against overwhelming forces that are historically dominant? This year’s edition of March Meeting—Sharjah Art Foundation’s (SAF) annual convening of artists, curators and other practitioners since 2008—followed this line of inquiry, revealing the ways in which contemporary art and culture’s modes of organization provide not only channels for discussion, exchange and healing, but also propositions of emancipation from post-colonial traumas in order to forge new narratives.

Under the title “Active Forms,” the three-day symposium focused on the dissemination of culture to the public via channels such as exhibitions, lectures and festivals, looking at how, from these arenas, ideas for endurance spring forth. Accompanying the various discussions and performances around this theme was a group exhibition, eponymously titled and featuring the works of 13 artists and one artist group, including Halil Altındere, Simone Fattal, Gulnara Kasmalieva and Muratbek Djumaliev and Naeem Mohaiemen.

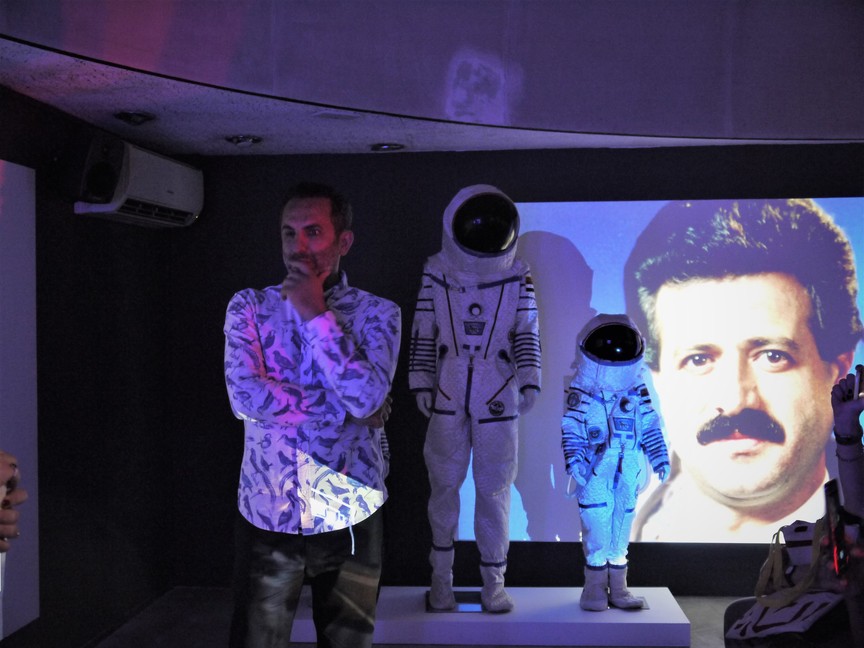

The exhibition was spread out across various venues, managed by SAF, augmenting the overall idea that these dialogues about our future are often informal—hidden, even. In the Old Sharjah Planetarium, a dome-shaped building painted robin-egg blue, was Turkish artist Halil Altındere’s “Space Refugee” project (2016), in which the artist proposed re-habitation on Mars as a solution to the Syrian refugee crises. At Bait Al Shamsi, a traditional site with Arabic architectural flourishes built in 1845, the works of several artists inhabited the studios overlooking the central courtyard. Hazem Harb spoke of impermanence and the lives of exiled Palestinians through the mixed-media installation Sustainable Living (2012), while Raeda Saadeh, in her video, revealed the futile act of vacuuming a valley range choked with dust, sand and rocks, in an attempt to “clean up” insolvable situations or landscapes. Simone Fattal’s leggy, hand-pinched sculptures was a more obscure addition to the exhibition, but the works, with their archaic forms borne out of Fattal and her partner Etel Adnan’s ongoing dialogue with the Lebanese civil war, nevertheless conveyed a sense of timelessness.

The first session on March 17 kicked off with a panel moderated by independent curator Zeynep Öz, on the topic “This is Not a Programme.” Four speakers, each from established institutions in their home cities of Cali, Colombo, Beirut and Istanbul, discussed the genesis of their various projects and alternative methods of practice in different spaces. Abir Saksouk, an architect at Public Works in Beirut, explained the efforts of her team in tackling urban inequalities through design and architectural intervention, such as in a project that aimed to preserve designated public play areas for children in Beirut. In Public Works’ findings, they noticed that almost 85 percent of fields for children had disappeared or were replaced by other sites over the past decade, and because of this, the youths of the city perform acts of transgression—claiming privately owned plots as their own, jumping over fences, tagging areas to demarcate football fields. Sharmini Pereira, founder of Raking Leaves publishing house in Colombo, argued for the artist book as a form of art itself, one that is a “fragile vehicle for the weighty load of hopes and ideas,” as quoted by American writer and art critic Lucy Lippard. Alper Turan of DAS Art Project in Istanbul looked back on the organization’s various projects housed in temporary or unorthodox spaces, and Sally Mizrachi traced the evolution of Cali’s Lugar a Dudas, from its founding moments to its establishment today.

SHARMINI PEREIRA speaking about Raking Leaves, a nonprofit publishing organization in Colombo, and the possibilities of public accessibility and public service in producing books.

After this institutionally-focused start to the event, two artist performances preceded a lunch break: Rheim Alkadhi presented a poetic speech on the ravaging of nature and the oppression of its protectors, led by a succession of monochrome images of landscapes; and Paribartana Mohanty’s video and lecture What if the Wind Refuses to Carry Our Words? (2018) probed issues of discrimination and labor in India in order to discuss the idea of “return” or “returning,” juxtaposing footage such as an interview of Narendra Modi with Matisse-style figures, and a clip of the cartoon Tom and Jerry.

The extremely packed panel talk “Terms of Order” opened the second half of the day, with artists Marwa Arsanios, Dale Harding and Naeem Mohaiemen. (Unfortunately, the fourth artist, Zineb Sedira—whose large solo exhibition was also being presented by SAF—had fallen ill and was unable to participate in the panel.) Steered by independent curator Tarek Abou el-Fetouh, the discussion bounced between the practices of the individual artists, examining the contribution of each in bringing to the fore marginalized narratives through community work, and more fluid discourse about what it means to be a diaspora or a global artist. Harding revealed that his recent work invoking parietal art, installed at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2017 for “The National: New Australian Art,” was co-created by himself, his uncle and his younger cousin. Through this act, Harding—whose lineage is related to the Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal peoples—invites the younger and elder generations to take part in the ritual of extending Aboriginal culture in an institutionalized space.

By this point in the afternoon, most of the crowd had begun to drift in and out of the auditorium in search of caffeine, which was a shame, as those beat by the already-intensive day would have missed the very brief, yet fascinating dialogue between artist Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim and SAF curator Noora al-Mualla, about the artist’s multi-decade career, which was accompanied visually by his retrospective, presented across three of SAF’s spaces. Immediately after was Ali Cherri’s presentation on mud and flooding. While both these talks did not exactly intersect with other practices or directly discuss the modes of organization as resistance, in Ibrahim’s work, one can see a pushback against the desert of contemporary art that surrounded him in the late 1980s and ’90s, and in Cherri’s, the idea of fertility and growth alongside destruction and devastation. This was followed by a screening of Omar Amiralay’s Flood in Ba’ath Country (2003), which traces the construction of Syria’s Euphrates Dam, an example of the move to modernize the country by then-President Hafez al-Assad.

I had to miss dinner due to sheer exhaustion—the Sharjah heat was on full blast at lunchtime, which although lovely, was seated outdoors—as well as wanting to stay awake during the final performance of the day, by Alexandrian artist Wael Shawky in Calligraphy Square.

Shawky’s piece, The Song of Roland: The Arabic Version (2017), premiered at Theater de Welt in Hamburg in 2017, and is a retelling of the classic French epic poem about the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778, in which Charlemagne, king of the Franks, campaigned against the Islamic Saracens. Enlisting roughly 20 musicians in the fidjeri tradition—a style originating from the pearl divers of Eastern Arabia’s coastal Gulf states—to narrate the story in translated Arabic, Shawky presented an hour-long performance that oscillated between melancholic and quiet, to boisterous and violent. Accompanying the song and occasional dance was a large, slanted, three-dimensional backdrop depicting the various sites of conflict in what is now Spain and a horizontal lightbox above this that indicated the varying chapters and motifs in the historical tale. This remix of the story, told from the Islamaphobic perspective of the French, yet vocalized by these fidjeri singers, subverts the singularity of historicity and instead suggests multiple interpretations of the past and present.

Ysabelle Cheung is managing editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

“March Meeting 2018: Active Forms” takes place from March 17 to 19, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.