R

E

V N

E

X

T

It has been a decade in the making, and none have anticipated the opening of Louvre Abu Dhabi more than those who live and work in the United Arab Emirates. From the feverish multitudes of billboards and flyers decorating the city’s airport, avenues and buildings, to a reliable build-up of arts programming throughout the city over the past ten years, it seems that an odd mixture of rewarded patience and hysteric elation has seized the UAE’s capital. This air of conviviality ensures that all roads this month lead to Saadiyat Island, where the first institution to be built looks, from afar, like a silver button amid a triumvirate of unbroken sea, sky and sand.

As one drives closer, the geometric dome and its contents within appears to rise from the bay, a vision that mimics its origin story from an arid strip of land to an inimitable institution, nurtured by the waters around it. Pritzker Prize-winning architect Jean Nouvel, in a presentation given at the official press conference in the museum, recalled his first visit to Saadiyat Island, revealing that, as he stared down at the land from a helicopter, he envisioned a kind of Grecian agora, a forum where art and life could be discussed. In a spiritual sense, the 180-meter dome is a homage to classical Arabic symbols and structures—overlapping motifs often seen in sites of worship. In a more pragmatic but no less wondrous sense, the roof at once offers respite from the glaring sun and refracts its rays to create a dappled, luminous sea of stars beneath its dome—a similar effect that is present among the palm tree-lined farms of the famed Al-Ain oasis, a location that partly inspired the vision of Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, the former emir of Abu Dhabi and the first president of the UAE, to build a green Abu Dhabi.

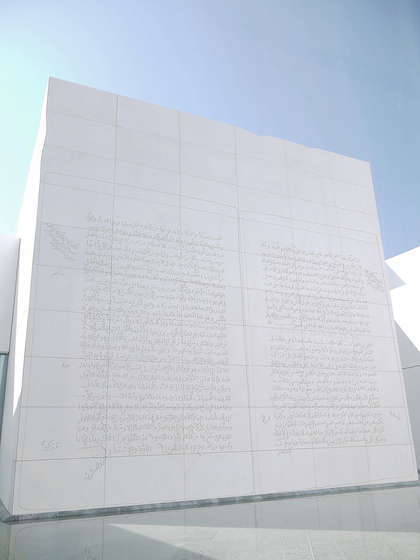

Under the dome, there are new commissions: multiple limestone relief texts by Jenny Holzer and works by Giuseppe Penone, one of which is a spindly bronze tree, naked save for mirror shards resting on its branches. Dotted around these are 55 individual buildings that make up the Louvre Abu Dhabi, 23 of which are galleries. Within these galleries, 235 international artworks belong to the young institution’s own collection, several are on loan from the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi—including photo documentation of Hassan Sharif’s performance on the Hatta dunes, Walking No. 2 (1983)—and another 300 are on loan from 13 French museums as part of an unprecedented cultural agreement between France and the UAE that will last for another 30 years and six months. In a first for a museum of this size, all the works are displayed not by geography but by chronology, forming a cohesive, global narrative that confronts the orthodox and divisive conventions of regional distinction. For example, to illustrate the impact of Islamic art on the Renaissance and vice versa, a luminous portrait painted by Leonardo da Vinci lies adjacent to richly decorated panels of mathematically inclined floral geometry—examples of a style that flourished in the Arab-Islamic world during the 15th century. During the press conference, the museum’s director, Manual Rabaté, made an impassioned argument for universality and commonality between people in this newfound direction, quoting the Roman playwright Terence: “I am human, and I think nothing of which is human is alien to me.”

To that end, the promise made by Rabaté and the others figures at the press conference—including Jean Nouvel and Jean-Luc Martinez, president-director of Musée de Louvre and chairman of the Scientific Board of Agence France-Muséums—was one of commitment to the Emirati people and global unity. “It is a gift,” said Mohamed Khalifa al-Mubarak, chairman of the Abu Dhabi Tourism and Culture Authority as well as the Tourism Development and Investment Company. “It will broadcast tolerance and acceptance.” Adding to that, the museum’s deputy director Hissa al-Dhaheri—notably the only woman, and one of Emirati origin, to speak at the press conference—revealed that two-thirds of the current staff at the institution are from the Emirates, and that a city-wide program to educate children about the museum’s collection has been successful. “That’s 190 nationalities, across all schools and universities,” she explained. “Creating a tool that would work was challenging, but when children are inspired, we are inspired.”

The modern section of the museum included works by high-profile artists such as ROBERT SMITHSON, KAZUO SHIRAGA, ANDY WARHOL and PIET MONDRIAN. In a corner of the space, almost hidden from view, was a seminal work by HASSAN SHARIF, Walking No. 2 (1983). In the photo documentation, one sees Sharif, the founding father of contemporary art in the UAE, walking across sand dunes in Hatta, Dubai, in an early example of the absurdist, process-based slant of his practice. The work is on loan from Guggenheim Abu Dhabi.

The next 30 years and six months also pose a challenge, not just to the Louvre Abu Dhabi but to Saadiyat Island—and indeed the rest of the region. What will the UAE become? How can a museum or a place be universal and true to its roots? As with the intended mission of the museum, one is left with more questions than upon arrival.

Ysabelle Cheung is the managing editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

The Louvre Abu Dhabi opens on November 11. Its inaugural exhibition, “From One Louvre to Another,” kicks off on December 21, 2017.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.