R

E

V N

E

X

T

Going out but always coming home again: Liverpool Biennial 2016

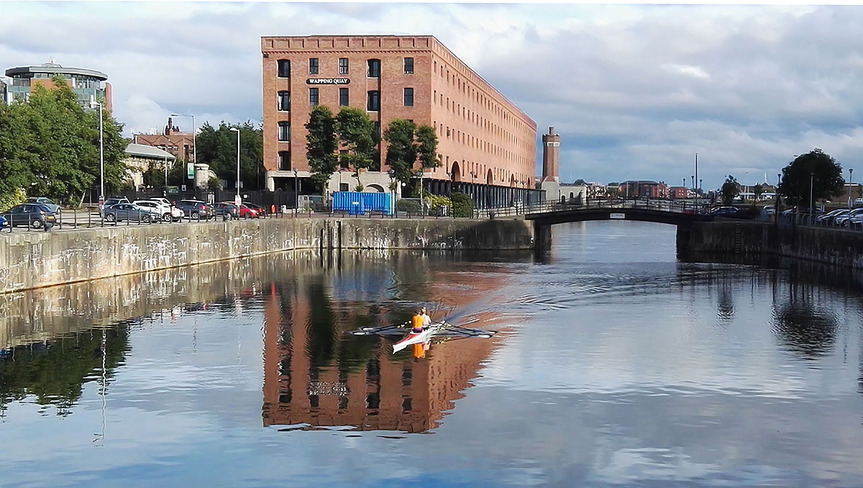

Having opened in July, the Liverpool Biennial (7/9–10/16) has been marked the “post-Brexit festival.” Like the rhetoric of the exit faction, it is also seen as advocating the UK’s alliances to unspecified trading opportunities outside Europe, looking beyond to a muddled internationalism. A multifaceted spirit is being played out in the event’s six overlapping themes—“Ancient Greece,” “Chinatown,” “Children’s Episode,” “Monuments from the Future,” “Software” and “Flashback.” In other words, they are concepts that are broad enough to accommodate any idea or thought. This might sound like a willful structure, but given the nature of the large-scale cultural event, the long treks across town to its various venues has led the art-viewing experience to mingle with the historic elements of Liverpool.

The display of 44 art projects at 22 different sites has allowed the city to throw open some new and magical venues, such as a derelict art deco cinema only a stone’s throw from the city’s main railway station, a battered and abandoned former brewery, and a neoclassical oratory; but none could be described as the primary exhibition space. Marvin Gaye Chetwynd’s musical film, Dogsy Ma Bone (2016), performed by students from local schools at Cains Brewery, encompasses at least three Biennial themes—a children’s episode, a flashback, and a future monument—with its final scene even taking place on the steps of a neoclassical bank. Brechtian in vision, Dogsy Ma Bone exposes the mechanisms of production and sociopolitical themes of capitalist greed, with a delivery by nonprofessional actors. In fact, Chetwynd brings out pure performances from the cast that balance real-life grit with innocent folly.

While travelling between venues has gotten visitors into the city streets, the gesture is charmingly inverted by American artist Jason Dodge’s What the Living Do (2016). At many sites, including Tate Liverpool, Dodge collects small offerings of trash left behind by revelers, such as empty bottles or paper and leaves gathered into a corner by air currents, and with the utmost nonchalance deposits them at the gallery. The garbage is deliberately annoying, testing both the audience and venue on what they can welcome as art. The Tate also presents a show mixing antiquities from the local Ince Blundell Collection with diverse contemporary works, but the subtlety of the classical fragments is disturbed by the bravura of the new, resulting in a feeling of languid competition that makes both old and modern seem weak and uncertain.

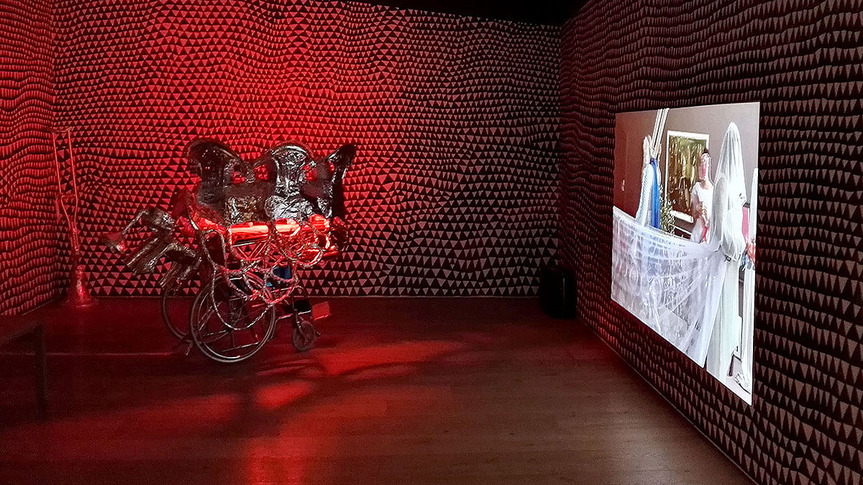

A mini retrospective of Polish born Krzysztof Wodiczko at FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology) explores the theme of displacement in the form of temporary shelters. In the work of Ramin and Rokni Haerizadeh, and Hesam Rahmanian—who are frequent collaborators based in Dubai—displacement is approached through phantasmagoric exploration. Creating “extreme” assemblages and videos of fervent performances, their works explore a scenario concerning the experiential antics of a trio of alien characters, something like “Third Rock From the Sun” meets Paul McCarthy. Their works appear in multiple settings along with that of Indian sculptor Sahej Rahal, whose awkward and provisional structures, some scattered across desks, look like temporary occurrences in public places, and feel as if they have come from another galaxy. Lara Favaretto’s Momentary Monument—The Stone (2016) is another alien presence, poised in a street set for redevelopment. It is a huge, seemingly unassailable block of granite, but the denouement is that it, along with the street, will be demolished at the end of the Biennial.

International biennials tend to seize on heritage, putting interesting, and hopefully great, art into elegiac locations. Liverpool, as such, has a rich intangible cultural heritage, which makes it a city that is more than its buildings, harbor, trade and cultural renovation.

Below are some other highlights from Liverpool Biennial 2016.

Liverpool Biennial 2016 is currently on view in Liverpool, UK, until October 16, 2016.