R

E

V N

E

X

T

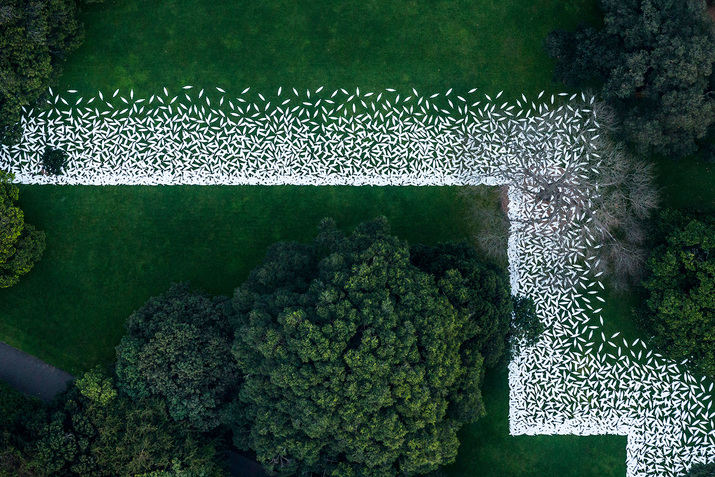

Aerial view of Australian artist JONATHAN JONES’s installation barrangal dyara (skin and bones) at the Royal Botanic Garden in Sydney, as part of the 32nd Kaldor Public Art Project. Photo by Peter Greig. All images courtesy Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney.

If Aboriginal Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones had got his way, there would have been 60,000 replica Aboriginal shields marking the footprint of the long-since-destroyed, 19th-century Garden Palace, located in Sydney’s Royal Botanic Garden. “I wanted 60,000 but John Kaldor said no. I had to settle for 15,000,” Jones confided to ArtAsiaPacific at the recent media preview for his 20,000-square-meter installation, barrangal dyara (skin and bones). The life-size shields delineate the history of the Garden Palace, which was built in 1879 and completely destroyed by fire in 1882.

Barrangal dyara (skin and bones) is the 32nd Kaldor Public Art Project (KPAP), a program that started in 1969 when art entrepreneur and philanthropist John Kaldor brought husband-and-wife artist-duo Christo and Jeanne-Claude from New York to Sydney. For the inaugural KPAP, the artists audaciously wrapped 2.4 kilometers of coastal cliffs in 93,000 square meters of fabric, which was held in place by 53 kilometers of rope.

Since then, Kaldor has regularly brought leading international artists to Australia to create works for KPAP, including Gilbert and George, Jeff Koons, Bill Viola, Tino Sehgal and Marina Abramović. Kaldor likes to think big, and Jones’s barrangal dyara is no exception; although, when the former commissioned the latter in 2014, the philanthropist had no idea exactly what the outcome would be. At the time Kaldor said he was looking for something that had “innovation, experimentation and the exploration of exciting new concepts,” and had tentatively named the project Your Very Good Idea.

Jones is the first Indigenous Australian artist to be selected for KPAP. Jones’ very innovative idea for the project was to recreate Sydney’s Garden Palace, an architectural marvel of the Victorian era that was purpose-built for an international exhibition in 1879, but burnt to the ground three years later and turned everything inside to ashes, including extensive and irreplaceable Aboriginal artefacts that had been collected for ethnographic reasons. Virtually overnight, the Indigenous culture of southeast Australia disappeared in flames. What remained, and what has filtered down across the decades, is what Jones refers to as “the propaganda of the white man’s view of Australia’s indigenous community,” which just this week was officially recognized as the world’s oldest civilization. Citing Nature magazine, The Guardian reported that DNA evidence has confirmed that indigenous Australians are the most ancient continuous civilization on Earth, with a lineage going back to approximately 50,000 years.

The propaganda that Jones is referring to is that which was propagated by the white invaders of Australia during the Victorian era (1837–1901). The British empire at the time saw Indigenous Australians as “Savage people in . . . [a country where] nothing was happening . . . [Indigenous] people were not cultivating the land or engaging in cultural activity. White fellas came along, took over the country and made good . . . the west was going to conquer the world and make it a better place. That is how aboriginal culture was framed.”

Initially, Jones had no idea how he would achieve his grand scheme. Back at the 2014 announcement of his project, we all thought that we would be seeing a life-size replica of the Garden Palace building springing up in the Botanic Garden, where its flower beds and perfectly manicured lawns would be ripped up in the process. “My dream would be to build it and then burn it,” Jones had told AAP rather mischievously.

The actual site of the building—which had been capped by a dome and was then the sixth largest of its kind in the world, modelled after St Pauls’ Cathedral in London—is now obscured beneath European-style planting and extensive lawns. Currently, the perimeter of this area is what Jones’s shields delineate.

The only flowers that have been ripped up were those that occupied the round beds that mark the site of the dome, which have been replaced by a mass planting of unruly kangaroo grass. The significance of this gesture is related to the existence of evidence that, 30,000 years ago, Indigenous Australians harvested the seeds of this grass to make bread. Until the relatively recent discovery of this fact, Egyptians from 15,000 years ago were thought to have been the earliest bread makers.

Through his work, Jones asks pointedly: “Why don’t we celebrate things like this? Why don’t we celebrate indigenous culture that stretches back even further?” Jones will continue to ask these questions during his daily on-site talks on the project grounds.

While the accumulated shields amount to little more than an empty spectacle, what Jones does celebrate in a masterful way is the revival of Indigenous languages, which he says is taking place around the country. Concealed throughout the Garden Palace site are several loud speakers that create a soundscape featuring different generations of Indigenous people each speaking their native language, of which there are many. Eight languages are represented here; while children’s voices repeat words by rote, elder voices orate old words from an ancient culture.

In barrangal dyara, Jones has turned the cataclysm of the Garden Palace fire into a paean for a civilization that was robbed of its identity and culture, and dispossessed of its land 200 years ago by those who are perceived today as invaders.

Barrangal dyara is possibly the most didactic of Kaldor’s projects so far and certainly the most political in tone. But whether it is successful as an artwork is a moot point, and perhaps there is a need to examine more closely what does or does not fall within the broad compass of art. However, what the installation does demonstrate is that Sydney has in its midst a young urban Indigenous artist, the like of which we have not seen before, who demonstrates a startling awareness and understanding of the issues involved in Aboriginality.

“Barrangal dyara (skin and bones)” is on view at Sydney’s Royal Botanic Gardens until October 3, 2016. For further details of related events and artist talks, visit www.kaldorartprojects.org.au.