R

E

V N

E

X

T

View of the hilltop city of Mardin and the former German Military Headquarters used as one of the venues for Mardin Biennial 4. All images by HG Masters for ArtAsiaPacific.

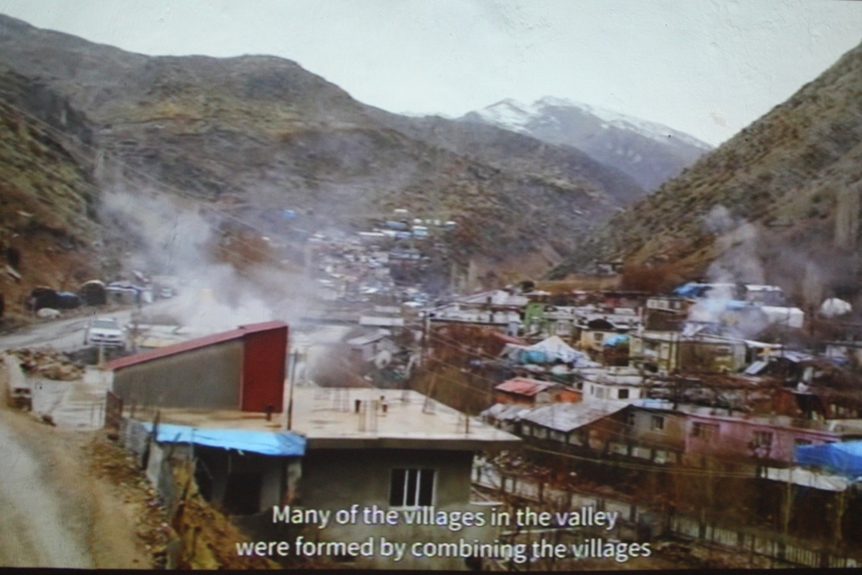

The 4,000-year-old hillside city of Mardin, with golden-stone buildings dating back to the medieval era, overlooks the fertile plains of what was ancient Mesopotamia, and is a spectacular setting for a biennial. All the beauty, contradictions and pain of the past, present and encroaching future are there. Just 21 kilometers from the border with Syria, the citadel is a Turkish military base, with a giant illuminated profile of Atatürk that is switched on after the evening call-to-prayer. The shop signs are in Turkish; the shopkeepers and tradesmen greet each other in Kurdish. Assyrian-made wines, herbal soaps, stone-ground coffee and elaborate jewelry are sold in the shops below ornately detailed stone konaks (“mansions”), madrasas and mosques, monasteries and churches. Black armored vehicles patrol the main street between tourist coaches and local buses. Syrian women and children sell tissues in the streets. The “great green” sea—which is truly what the Mesopotamian plains resemble from Mardin—leading from modern Turkey through Syria into Iraq and the Gulf, is in deep, tragic sectarian conflict.

And then there is contemporary art. For the fourth time since 2010—with three years’ interruption, after the third edition in 2014 was postponed for six months as Kurdish fighters and ISIS battled over the Syrian border city of Kobane—the Mardin Biennial opened on May 4, and runs for one month at ten venues in the city. It was a fairly shambolic affair in terms of organization—particularly with the communication of where artworks were located and when performances were happening, as well as the installations of several works—and yet it was almost entirely forgivable given the setting (the two largest venues were dilapidated stone structures, with dusty, crumbling interiors and low doorways) was not in any way equipped for the video projections, multimedia installations, or large groups of Istanbul and Ankara visitors, especially when spring storms inundate the hillside, as it did on the afternoon of the biennial’s first day.

“Beyond Words” is the biennial’s title, and an appropriate one for all that can and cannot be said about what is happening in Turkey and the region. To that end, the biennial has three curators and three interwoven concepts that create a dialogue between the artworks and the city. Fırat Arapoğlu’s proposal, “Infinite Sight,” looked at geography, spatial politics and aesthetics; Nazlı Gürlek’s “Body Language” suggested that the most elemental form of communication comes through the body; and Derya Yücel’s “Boundaries and Thresholds” bridged the two to look at contested spaces.

Despite the intense pressure on public speech these days in Turkey (the Kurdish opposition leader has been jailed since November 2016; government-linked conglomerates now have near-total control of the media; more than 100 journalists are currently behind bars for terrorism-related charges; tens of thousands of prosecutions have been made for online “insults” of the state and president; and vigilante campaigns against students, activists and professors are increasingly common), there is, for now, still some potential for critical conversations through cultural events.

There were many artworks addressing sensitive political subjects in the exhibition at the Mor Efrem Monastery, a late 19th-century compound built by the Syriac Patriarch (whose congregants, along with the Armenian community, were almost entirely wiped out or forced out in genocidal purges by Ottoman soldiers and Kurdish militias during World War I). Using digital maps and photographs, Serkan Taycan’s video HydroLab Mesopotamia (2018) illustrates what is known and what is being kept secret about the Turkish state’s plans for a series of dams and new lakes on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers that both eradicate local communities and create a watery border perimeter. Among Taycan’s revelations are details about the construction of three “security dams,” two of which currently hold no water but block valleys used by Kurdish smugglers and militants to move through the region. Tackling another sensitive issue was Nasan Tur’s three-and-a-half-hour video Memory as Resistance (2017), showing photographs of assassinated journalists—including Armenian-Turkish newspaper editor Hrant Dink, whose killing outside his Istanbul office in broad daylight in 2007 remains an unsolved mystery—being crumbled up and then smoothed out, in a metaphorical cycle. İpek Duben’s book and video, Farewell My Homeland (2004), comprising silkscreened images of displaced people from throughout the 20th century, was a grim anthology of the human suffering that is still so prevalent in the region.

In many works in the Mardin Biennial, symbolism veered precariously toward the overt. Beautifully shot, Senem Gökçe Oğultekin’s 13-minute video (produced in collaboration with Levent Duran) captures a performance-collaboration with dancer Gasia Papazyan in the ruins of the historical border city Ani. The vignettes of the two women’s gestures—including shots of their hair braided together, or of them appearing to fight like siblings—though easily recognizable as representing the fraught Turkish-Armenian relationship, also evoked familiar, nostalgic sentiments around the subject of reconciliation (which, of course, is better than the vituperative nationalism and genocide denial that is the official Turkish policy these days). Another of the obviously topical works, shown at the former German Military Headquarters, was Fırat Bingöl’s video O Water (2017), capturing the artist making wishes on the Tigris river in the village of Hasankeyf, a 12,000-year old settlement that will be submerged later this year as part of Turkey’s dam projects.

More artistically challenging representations of the landscape can be found in Mahmut Celayir’s two paintings, one a sepia-toned image of a valley with a red-and-white surveyor’s pole attached to it, titled Ware (2017) (meaning “plateau” in the Zaza language), and the rhythmic, abstract canvas An Afternoon of a Voyager (2016), which seems to respectively suggest both a bleakly rational and lively spiritual relationship to the earth. Similarly working with abstraction but in physical and spatial terms was Aslı Bostancı, whose improvised sound-dance performance appeared to channel spirits and energies via gestures and wordless singing. A program of videos documenting landscape-performances (1978–81) by Ana Mendieta, and Chaw Ei Thein’s video Body to Body (2016), in which the artist re-enacts iconic Burmese performance artworks, elaborate on the idea of the body being both a victim of oppression and the site of potential resistance.

A crucial reason for the biennial’s existence is to showcase artists from the southeast region of Turkey. Cengiz Tekin’s project was 200 meters of sky-blue “protocol carpet” crisscrossing a square, bridging door to door, as a supposed means to forge links between the tradesmens’ workshops, various private spaces and the public (the carpet was quite dirty and water-logged when I saw it, and the shops were closed). İhsan Oturmak had a white car wedged on the steps of a narrow street one evening as part of his project Difficulties of the Street (2018) (not knowing where it was or that it was even happening, I only saw photos later). Metin Çelik’s installation Anti-Camouflage (2018), of a large, metallic-orange fist, electric-blue wallpaper, which covered the walls and floor, and a painting of people pressed between concrete walls, was, in its messaging about authoritarian power, very overt. So was Mürsel Argunağa’s untitled sculpture that features parts of three plaster figures (mother-father-child), arranged as if being crucified, against a machine-woven carpet. More nuanced was Eda Aslan’s installation of wooden containers, A Piece of Land and Others (2018). A mold of a tree from the house where she was born was on one of the boxes, while black stones, sand and a gilded pigeon feather were featured on the others, and sounds of the breeze and birds were projected in the space.

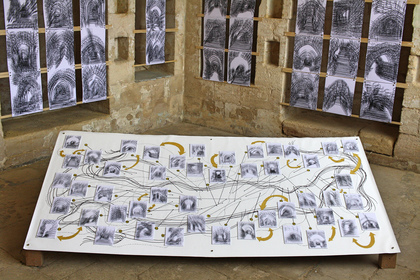

Mardin itself made for an interesting place to look at art. I appreciated Çağrı Saray’s installation Infinite Distance (2018), which mapped the distinctive stone archways of Mardin known as abbara. I enjoyed the incongruity of watching Chris Burden’s performance videos from the early 1970s playing on a monitor by a table in the cosy Marangozlar (“Carpenters”) Café, even if the sonic conditions of the space and Burden’s narration in English likely made it difficult for most locals to understand (though there is a full transcription of his commentary in Turkish on the table by the monitor). Canan’s installation of fabric works of folkloric creatures in the Yıldız Hamam had a visually appealing presence. Situating her work in Mardin—rather than more pristine gallery spaces in Istanbul—brought the pieces back to their material home, allowing Canan’s compositions to resonate with the designs of the city’s artisans. Unfortunately, the installation of a video and photographs by Youssef Nabil of a Christ-like figure, in the outer part of the same hamam, was one of several instances where the poor quality of the installation and low-grade monitor really did detract significantly from the cinematic qualities of the work.

As the largest and most ambitious iteration of the event to date, the fourth Mardin Biennial revealed the institution’s growing pains, between its aspirations and production. For instance, John Gerrard’s one-year-long digital simulation Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas) (2017)—which depicts a black flag created from smoke emitted from the top of a flagpole at the location of the world’s first major oil discovery, the “Lucas Gusher”—evokes not only the black flag of ISIS but the burning oil fields of Iraq after the first Gulf War, as a grim monument to the violence of the petro-carbon era. The work was rightly a hit with everyone, and stood out for its conceptual and technical sophistication. The fact that the modest biennial did manage to arrange the installation (with help from Istanbul supporters and technicians) was great, though it also suggested that the biennial could actually improve aspects of its production without forsaking its local characteristics. The other artist whose work everyone treated with deference is Taner Ceylan. His painting, The Man of Sorrows (2016), was displayed inside the Virgin Mary Church. It blended almost seamlessly into the environs and the church’s other devotional imagery, except for the undercurrent of eroticism that the artist brings to his exactingly executed paintings. What makes Mardin such a unique place is its history of craftsmanship, evident in its enduring architecture and artisan metalwork. It’s an aspect of the city that the biennial itself could draw upon in its own production values for its next edition.

HG Masters is ArtAsiaPacific’s editor-at-large.

Mardin Biennial 4 ends on June 4, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.