R

E

V N

E

X

T

YAZAN KHALILI, photo of Boeing 707 airplane taken near Nablus, in an abandoned amusement park, in the West Bank. Khalili’s photograph is used on the poster of Qalandiya International, 2016. All photos by HG Masters for ArtAsiaPacific unless otherwise noted.

Day 1: Terms of Engagement

The poster for the third edition of Qalandiya International (QI) features a weathered, wingless Boeing 707 airplane propped up on metal pilings in a barren lot. Taken near the West Bank city of Nablus in an aborted amusement park, the photograph by Yazan Khalili condenses many resonances of QI—a biennial festival named for a place that was once a village on the road between Jerusalem and Ramallah, then home to the first international airport in the British Mandate of Palestine, and today is the dismal site of a refugee camp (since 1949) and the grimly notorious Israeli military checkpoint in the occupation wall. In Khalili’s photograph, the wings of the plane have been sawed off and its nose is pointed toward the hills in the background, a symbol of aspirations (personal, national, cultural) grounded, clipped and left to erode. In the shadowed foreground is an equally incongruous abandoned sailboat—a long way from any sea.

The press conference of Qalandiya International 3, on October 5, 2016, at Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center in Ramallah. From left to right: Aline Khoury, the coordinator at al-Ma’mal Foundation for Contemporary Art in Jerusalem; Mahmoud Abu Hashhash, director of the arts and culture program at the AM Qattan Foundation; Eyad Barghuthy, general manager of the Arab Cultural Foundation, Haifa.

“The Sea is Mine” is the title of QI 3, but on the first morning, in the hills of Ramallah, just 28 miles from the shore of the eastern Mediterranean, the sea felt a long way off. At an elevation of nearly 1,000 meters, the Ramallah sun was strong and the air dry. The press conference took place on the top floor of the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center, a handsome old stone manor with a large fig tree in its garden. Established in 1996 by the Palestinian Ministry of Culture, it’s named for the Palestinian journalist, educator and early Arab nationalist. With Sakakini’s photograph behind him, Mahmoud Abu Hashhash, director of the arts and culture program at the AM Qattan Foundation, and a poet in his own right, outlined the thematic agenda for the month-long festival of Palestinian contemporary art. Hashhash explained that QI was designed to address, and also overcome, many of the limitations on Palestinian life that are the ongoing legacy of the 1947–48 Nakba (the “Catastrophe,” when Zionist paramilitary groups and later the Israeli military forced more than 750,000 Palestinians out of their homes). He called the sea a part of the Palestinian peoples’ “spiritual geography” and recalled that the “loss of the sea” is a central component of Palestinian discourse around the Nakba and the “Palestinian Return." The latter is one of the three pillars of the Palestinian national movement, along with the right to self-determination and the establishment of an independent state with Jerusalem as the capital. Avoiding some of the harsh words used in the printed QI curatorial statement—that “return” has become a “rigid slogan,” “static and empty of meaning,” and “diminished to the merely symbolic realm of visual culture”—Hashhash explained where QI would try to position itself in relation to this official discourse. He noted that this idea of “return” is usually presented by politicians for public consumption without any real reflection on the current realities, but that QI had selected it as the theme, because it was up to cultural figures to offer fresh approaches. “No one is more capable of that than artists,” he said.

As organizers laid out the thematic parameters of QI that morning, they were also outlining some of the contours of Palestinian cultural and intellectual life. No one openly said that the idea of seven million Nakba survivors and their descendents returning to their former homes in places that are now within the state of Israel—many of the houses and towns don’t even exist any more, having been demolished or taken over—is not a realistic expectation. (Although, in private conversations, several people characterized “the right of return” rhetoric in unexpectedly profane and emphatic variations of “bullshit.”) Yet it was also clear that real expressions of solidarity are very important, and also necessary, especially when trying to create a space for critiques of the symbolic foundations that have traditionally underpinned that very same solidarity. While the motivations behind QI felt very much to be in the vein of constructive criticism, Palestinian society has its own fragile balance at the moment. It remains under tremendous stress from the ongoing Israeli military occupation and is becoming even more geographically fragmented. It is also struggling with its own internal political, religious and class divisions that further threaten a sense of unity between Palestinians.

Similar dynamics prevail on the structural level of QI. QI’s programming relies on broad coordination. The morning’s second speaker, the novelist Eyad Barghuthy, who is also the general manager of the Arab Cultural Foundation in Haifa, explained that QI is a “horizontal partnership” between 16 cultural organizations, from Ramallah, Birzeit, Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Gaza, to Haifa, Amman, Beirut and London. There’s no central curator, so the organizations, acting in concert, but each with varying levels of funding and abilities, and with different audiences and communities in mind, use QI as a collective platform to broadcast their programs further afield—with greatly varying results, as I would see in the coming days. After Aline Khoury, from al-Ma’Mal Foundation in Jerusalem, outlined the month’s events, the press conference finished with a hint of frustration. Someone asked an indignant question about why no one had mentioned that the title “The Sea is Mine” is a line from one of Mahmoud Darwish’s poems, Mural (2000). One answer came from a startled-looking Hashhash, who remarked that it is such a well-known line he thought that it would be obvious to everyone.

After the press conference came the bus. That’s a feature common to nearly all international art events. Organizers took us around on a rapid tour of the venues in Ramallah where the QI exhibitions are being held, although most of the specific shows still hadn’t been fully completed yet, since their openings were staggered over the evenings of the coming week. The first stop was Housh Qandah, in the Old City of Ramallah, where, in “Sites of Return,” co-curators Sahar Qawasmi and Beth Stryker took the theme in several directions: in their words, toward “restlessness, rupture, rebellion, re-growth and radical forms of action.” The projects reflect many of the new dynamics in West Bank life. Mohammad Saleh’s Yaleekom (2016), for instance, is an urban gardening project in and around the building’s courtyard. It reflects a larger trend toward “self-sufficiency” among Palestinians, particularly in the area of agriculture and food. Since Israel controls the water and much of the farmland in the West Bank (so-called Area C) most of the food that Palestinians consume is Israeli-produced—one of the bitter aspects of the occupation. At breakfast just that morning I had read about young Palestinian entrepreneurs who recently established their own mushroom farm in Jericho to compete with Israeli farms.

Inside Housh Qandah is a room of newly created abstract paintings, tacked to wooden stretchers, by Jerusalem-born Samia Halaby, an artist now in her 80s. With titles like Organizing, Pathways, Political Prisoners and Book of Martyrs, the works in the “Return” series (2016) are all visually based on patterns of overlapping squares and are meant to evoke various natural processes of formation and convergences of people. Next door, in two adjacent rooms are Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s tension-filled, rapid-cut audio-visual travelogues featuring two anonymous male protagonists visiting sites in the West Bank, Incidental Insurgents I & II (2012, 2014), which, though I had seen them before, felt particularly exhilarating in physical proximity to the landscapes where they were filmed. Upstairs, Basim Magdy’s A 240 Second Analysis of Failure and Hopefulness (With Coke, Vinegar and Other Tear Gas Remedies) (2012) comprises a pair of slide-projectors displaying partially overlapping photographs of a demolition and construction site, which he developed with chemicals that give the images streaks of bright color. In this context, I read them as an unstated reminder of the long history of house demolitions by the Israeli military since 1948, as well those structures being lost in Ramallah as the city undergoes a building boom that seems incredible to nearly everyone.

“Sites of Return” includes several performative works that I didn’t get to experience fully during my week in Palestine. Campus in Camps’ project Book of Exile (2016), is a large book of stories about refugee life since the Nakba, rendered by the calligrapher Abdelghani Ouida during the Marrakech Biennale earlier in the year. It sat open on one table, and during QI, local Palestinian calligrapher Saher al-Kabi began making a copy of the book to remain in Ramallah. Rheim Alkadhi’s project similarly wasn’t completed until after I left, but she described it as involving stories written by women on the inside of their sleeves. Mirna Bamieh’s public storytelling project Potato Talks: (Up)rooting, staged on October 17 at al-Manara Square, featured people peeling potatoes and telling personal stories to those who gathered around. In Nida Sinnokrot’s event Flight – Jalazone (2016), which was scheduled for October 19, the artist released trained pigeons tagged with LED lights into the evening sky above the Jalazone refugee camp, north of Ramallah, in what I imagined to be a visualization of escape and return. Even though the exhibition was officially produced by the Municipality of Ramallah (but sponsored by the Heinrich Böll Foundation and Centre for Culture and Development, CKU)—and promoted very prominently throughout the city on posters and billboards—none of the artwork could be mistaken for anything close to official propaganda. The “sites of return” proposed in the artworks seemed to be largely conceived of as psychological states, ones rooted in remembrance of painful pasts, an acceptance of the current realities, and measured about the future.

We then visited the ninth Young Artists of Year Award (YAYA) exhibition in another renovated historical building, the nearby Beit Saa, which I’ll describe in more detail in a later post, since we returned the following day for a more thorough walk-through. After that, our bus headed north out of Ramallah to the campus of Birzeit University, on the way passing through an unfortunate pair of ornate stone gates that the local municipality was erecting over the road, which induced groans of embarrassment from our local guides.

At Birzeit University, professor Yazid Anani gave us a tour of the “Cities Exhibition 5: Gaza – Reconstruction.” The first was an exhibition of projects by students from the International Academy of Art – Palestine, and the department of architecture at Birzeit University. As Anani explained, young people in the West Bank are very interested in Gaza and feel a strong solidarity with the one million people trapped in the coastal enclave, particularly after the intense bombing endured during Israel’s 2014 war with Hamas militants, but they also have very little information about life there and have no way to visit. So the exhibition’s first chapter questioned how to research Gaza, and in the second part, the art and architecture students made projects in collaboration with the Gaza-based Eltiqa arts group, reflecting their inquiries.

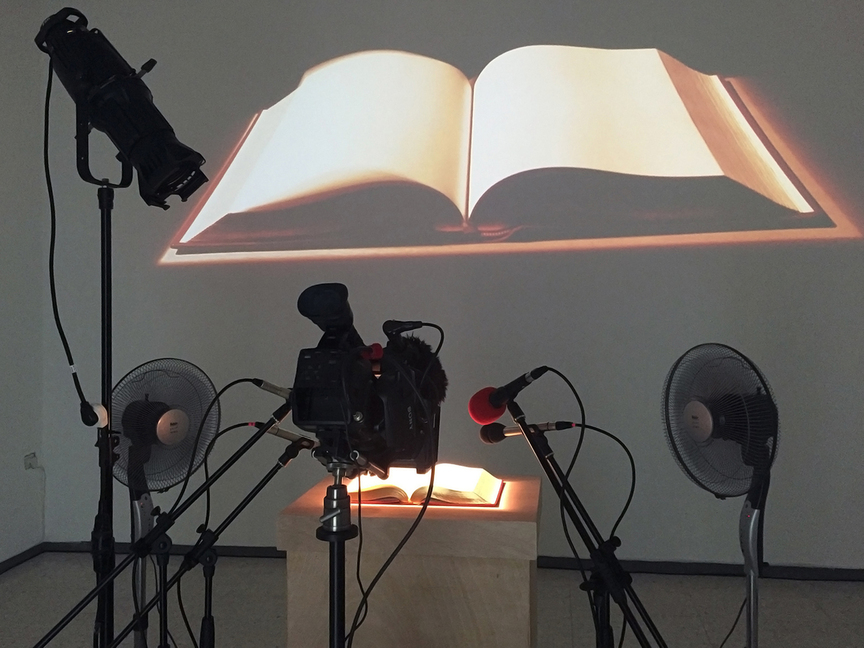

The third chapter expanded the inquiry into Gaza with works by seven more established artists and collectives. Oraib Toukan’s video, for instance, is a montage of Skype interviews with journalistic fixers in Gaza. Khaled Jarrar, an earlier graduate of the International Academy of Art – Palestine, looked at the afterlife of Yasser Arafat’s helicopter, which made many voyages between the previously united Palestinian territories, but ended up in Gaza, where Hamas transformed it into a local monument in the Ansar airfield. Other artists have gone further from the sociological and historical. Nida Sinnokrot’s Exquisite Rotation (2015) is a strongly allegorical work, consisting of a pedestal with an open book whose pages are turned by a pair of oscillating fans. Microphones in front of the podium amplify the sound and the whole scene is captured by a live feed and projected onto wall behind it. It felt like a monument to the emptiness of so many official ceremonies and announcements (here’s looking at you, Oslo). In another room, Wafa Hourani’s sculptural maquette The Cemetery of Things (2016) (also referred to as The Graveyard of Secrets) is a proposal for a burial ground that the artist cryptically describes as “how [on the one hand] the content of art is a science that constantly reinvents itself to describe disappearance before accessing it on the other.”

That evening was the opening of Sharif Waked’s show “Crop Marks” at Samar Martha’s Gallery One, where the artist riffed on ideas about iconoclasm with his own dry form of pop-inflected humor. The main feature of the exhibition is the “Dot.txt” (2016) series of canvases that at first glance simply resemble brightly colored polka-dot wrapping paper, but in fact contain bold, occasionally provocative slogans (“Arabs with Knives” or “Two Stater One Stater”) that were at first hard to decipher with the naked eye.

Afterwards there was a reception at the restaurant next door, where curator Sophie Goltz and I chatted with two young enthusiastic guys, named Amer Kurdi and Mohamad Rabah, a lawyer and a social-worker, respectively. Mohamad, who had just returned to Ramallah after getting a Master’s in the UK, has long worked with Palestinian youths, and vividly described the range of challenges young people face, from those who grow up impoverished in refugee camps to those whose parents sell their land or properties to put them through university, only to find there are not enough jobs in the West Bank. I was surprised then to learn that they are working on what they called a top-secret art project that I managed to glean might be happening early next year, perhaps with the help of the Qattan Foundation. Their project may involve staging an exhibition of things that might or might not be artworks where live-action role-playing unfolds in front of an unsuspecting public. They were interested, in their words and with genuine earnestness, in questioning the role of the artist, the gallerist, the curator, and to inquire about what is art, what is an exhibition and so on—all these fundamental questions came tumbling out. Perhaps more than anyone else I met that first day, Amer and Mohamad, even though they said they felt like outsiders in the Ramallah art scene, were excited to find a sphere where they could openly question and redefine all the established terms.

HG Masters is editor at large of ArtAsiaPacific.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.