R

E

V N

E

X

T

Same-sex marriage isn’t legal in Taiwan yet, but it will be soon. The territory’s highest court has already ruled that denying gay couples matrimony is a violation of “the people’s freedom of marriage” and “the people’s right to equality.” With that note in mind, the Sunpride Foundation and Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei (MOCA Taipei), collaborated to present an exhibition titled “Spectrosynthesis – Asian LGBTQ Issues and Art Now,” the first art show in Asia that tackles LGBTQ issues in a public art museum. Three years in the making and curated by Sean Hu, the show included some-50 artworks—mostly drawn from Sunpride founder Patrick Sun’s collection, with a few works on loan from other sources, such as the Taipei Fine Arts Museum—by 22 ethnically Chinese artists from Taiwan, Hong Kong, mainland China, Singapore, the United States and Canada. Though the exhibition opened as rains fell, one could not help but look ahead to the promised rainbows.

Ho Tam, who was born in Hong Kong and is now based in Vancouver, had careers in advertising and social work before becoming a full-time artist. After dabbling in painting, photography and filmmaking, Ho chose to make the medium of book publishing his own. The first issue in his “Hotam” series of books (2013– ) layers the artist’s life over major global events, with images sourced from treasured family albums all the way to recent snapshots. Each page represents one year of Ho’s life, and we see the artist’s growth from infant to adult as he marks significant milestones—for instance, the 1969 Stonewall riots in Greenwich Village, the 1985 release of the charity music album We Are the World, and the Burmese junta’s smashing of the 8888 pro-democracy uprising in 1988. In MOCA Taipei, Ho’s books were presented in recesses in the wall, where diffused sunlight illuminated each volume, as museum director Yuki Pan had envisioned.

Singapore artist Jimmy Ong’s charcoal drawings see same-sex couples entangled in loving embraces with their child, with gentle countenances and loving smiles. In Heart Daughters (2005), one woman carries her partner on her back, conveying not only familial love, but also a sense of incredible strength.

American-Chinese artist Wu Tsang’s video Duilian (2016) was shot in Hong Kong, and tells the reimagined tale of Qiu Jin, a Han-Chinese revolutionary who attempted to overthrow the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) in the late-19th and early 20th centuries, though a failed uprising led to her decapitation. Wu’s video unpacks the intimate relationship that Qiu maintained with calligrapher and publisher Wu Zhiying, with the artist herself playing the role of the insurgent. The artwork’s title refers to two things—couplet poetry and sword fighting. Between scenes with Cantonese, Malay and Tagalog laid over some of the dialogue, we see Chinese women practicing martial arts, even taking on Qiu’s friend—or lover—as a pupil.

In Talk About Body (2013), Tao Hui speaks for nearly four minutes about his physical characteristics—including facial features, allelic genes, toes and “wet” ear wax—to make the point that his body differs from the average Han Chinese male’s, and shares many traits with the Han Chinese female’s. For this exposition, the artist dons a black hijab and dress, and plays the role of a woman as his male body is described. The reasoning behind Tao’s choice of apparel is not clear, and its presence is complicated by the multitudinous meanings that the hijab holds for Muslim women across the globe.

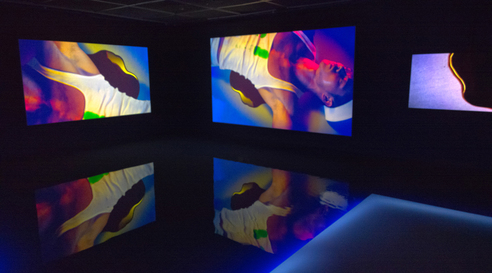

Taiwanese new-media pioneer Jun-Jieh Wang’s Passion (2017) was shown in his home country for the first time for “Spectrosynthesis.” The three-channel video installation was presented in a gallery filled with water, echoing the story’s setting at a dock at dusk. Wang appropriates images and themes from three films—Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Querelle (1982), Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Jean-Luc Godard’s Passion (1982). The short film, lasting just under 12 minutes, is action-packed: an astronaut steps out of a phallus-shaped pod and onto the dock, desire courses through two (male) sailors, a stabbing ensues, and a third sailor films as a voyeur through a hole in a brick wall.

Su Hui-Yu’s Nue Quan (2015) was inspired by a sad and gruesome case that happened in Taipei in 2001. Two men who met online engaged in sadomasochistic sex, which led to the death of one. His body was disposed in a suitcase. The case was closely followed by Taiwanese media, and the homosexuality of the two men were played up in news and tabloid reports. In Su’s two-channel video, we see a nearly naked man sitting alone on a bed, breathing in and out, with a plastic bag tied tightly around his neck. On the other side of the screen, another channel shows one man perform the clumsy act of folding and stuffing a nude, limp body into a Samsonite suitcase. The work’s title, Nue Quan, which means “dog abuse,” is taken from the username of the man who was charged with homicide in 2001.

In 2009, Ming Wong represented Singapore at the Venice Biennale. When he was in Italy, the artist researched the country’s history of films, and riffed off Luchino Visconti’s 1971 classic Death in Venice, which was based on a novella by Thomas Mann published in 1912, to create his own Life and Death in Venice in 2010. On the first screen of the three-channel video, Wong plays a gentle adagio on a grand piano that would not have been out of place in classic European cinema masterpieces that deal with themes of love, lust and passion. In the two other channels, we see the artist play two roles—an older mustachioed gentleman and a young sailor with voluminous blond locks—both modeled after the key characters in Visconti’s original. Wong’s older gentleman pines after the young sailor, who leads us through charming, tucked-away locations in the canal city. At certain points, the sailor looks back, knowing full well that he is being followed.

For Man Hole (2014–16), Hou Chun-Ming sought out 13 gay men, interviewing each for two days. Each subject drew himself—his self-perceived, true body—while in the nude (seen on the white sides of the hanging drawings). The artist also drew his own interpretation of each subject (seen on the black sides). At MOCA Taipei, text banners flanking the portraits added a new flair, invoking Taiwanese folk beliefs and similar streamers found in local temples. The texts were summaries of or excerpts from the interviews, and described each subject in his own words—“my body has poison,” “quivers and takes flight when caressed,” “needs to be raped.”

Brady Ng is ArtAsiaPacific’s reviews editor.

“Spectrosynthesis” is on view at Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei, until November 5, 2017.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.