R

E

V N

E

X

T

Recap of Khairani Barokka’s Annah: Nomenclature

Documentation of Indonesian artist KHAIRANI BAROKKA’s lecture-performance Annah: Nomenclature (2018) at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 2018. All photos by Christa Holka; courtesy the Institute of Contemporary Arts.

Embodying Paul Gauguin’s objectification of women, colonial gaze and pedophilia, Annah the Javanese (1893–94) was painted upon the artist’s return to Paris, after his first sojourn in Tahiti. The work shows a naked woman with light brown skin sitting in a chair, gazing directly at the viewer while a monkey lounges at her feet. Gauguin’s inscription on the back of the canvas identifies the sitter as his underage mistress Annah, who lived briefly with him in Paris. Today, the controversial painting is held in a private collection but has also gained a life of its own in popular culture. The scene of Annah posing for the painting is recreated in a 1980s biopic—with Donald Sutherland playing Gauguin—in the manner of softcore pornography, while Mario Vargas Llosa gives Annah a chapter in his novel The Way to Paradise (2003), which traces the life of Gauguin and his feminist grandmother, Flora Tristan.

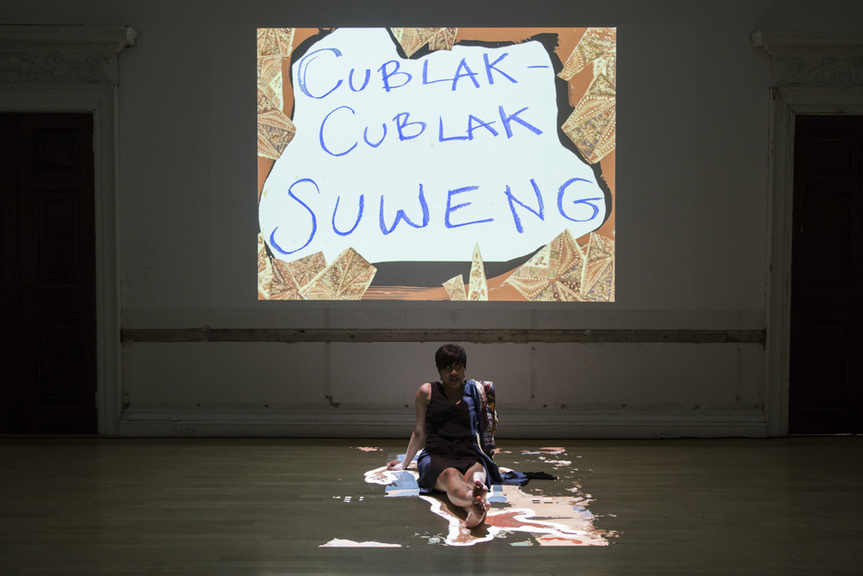

More recently, Indonesian artist Khairani Barokka has made Annah the subject of her research. On August 23, she staged a lecture-performance, Annah: Nomenclature (2018), at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, posing questions about race, sexuality, and patriarchal narratives in relation to Annah and women today. A copy of Gauguin’s painting was projected onto the floor of the Institute’s upper gallery. Immediately above this were Barokka’s slides, which relayed Annah’s biography, pieced together from the sparse fragments of information available, and the history of the painting. Throughout the performance, Barokka sat and lay down on the floor, such that the projection of Annah the Javanese was overlaid across her body while she recited her scripted speech in an exaggerated sing-song intonation that switched between English and Indonesian.

Barokka made connections between Annah—who has effectively been written out of art history—and the contemporary crises of the representation of minorities. Citing a Life magazine issue from the 1950s and Llosa’s book, both of which assert that Annah was 13 when she lived with Gauguin, Barokka argues that irrespective of the shifting legal definitions of the age of consent, Annah’s story is one of child exploitation. Besides exoticization, seen throughout Gaugin’s paintings of naked women, Annah the Javanese is child pornography. Quoting from Llosa, Barokka also outlined how Annah was passed between “patrons,” including art dealer Ambroise Vollard, known for first brokering interest in key 20th-century artists, such as Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Annah’s position as a domestic servant, abused, trafficked and shuttled between male owners, is a familiar story and contemporary examples of similar abuses flashed up on the screen. As she spoke, Barokka drew a line around the projected image of Annah, giving her a boundary and expressing how she wanted her to now feel safe. In this way, Barokka seeks to create a voice for Annah, who has been made mute and invisible by history.

Documentation of Indonesian artist KHAIRANI BAROKKA’s lecture-performance Annah: Nomenclature (2018) at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 2018.

Further, the performance drew attention to the hazy facts surrounding the making of Annah the Javanese. For one, Barokka tried to unpack the cryptic Tahitian inscription at the top of the painting: “Aita parari te tamari vahine Judith.” Gauguin’s neighbor had a daughter, Judith Molard, who was also aged around 13 when he convinced her to model for him. Barokka cited a theory that Molard was the original subject of the canvas, which was only later adapted to being of Annah. In either case, however, the painting presents a study of a young woman who is being robbed of her childhood.

Documentation of Indonesian artist KHAIRANI BAROKKA’s lecture-performance Annah: Nomenclature (2018) at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 2018.

Barokka expanded on the theme of lost innocence by singing Indonesian songs from her own childhood and getting the audience to join in with a cry of “You’ll remember this one.” Later, she recalled her family history as she talked about a photograph of her own mother at school, taken in 1965, while hinting at the context of Indonesia’s political turmoil at the time, though she kept the details of the communist and ethnic Chinese purges vague. That Barokka did not break the taboos that still surround these subjects was understandable but a shame, as the corruption of colonialism and society’s prejudices, whether in Gauguin’s work, or in the history of Indonesia, are issues that need to be broached.

Barokka’s attempt to recover Annah’s narrative also led the artist to question the identities that have been assigned to Annah. Rather than Indonesian, Tate’s database lists Annah as Polynesian, while other accounts describe her as Eurasian, Malay, or, as Barokka memorably shrieked, “Mulatto.” Echoing Adrian Piper’s performance Cornered (1988), the artist asks what other labels Annah might have claimed for herself if empowered: queer, mute, autistic or chronically ill. The performance became particularly disturbing when, drawing from scholarly European colonial texts from the 1890s, Barokka read out racist and sexist descriptions of Indonesian women that still crop up today.

Though a sense of anger was palpable throughout Barokka’s performance—particularly as it was hammered home that Annah was treated as worthless while alive, but her portrait is worth millions now, and even the traces of her image have become a commodity—Barokka concluded the performance with another childhood song and game, “Cublak Cublak Suweng.” With its simple analogy about looking for treasure, the chant appeals for us all to be generous and compassionate.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.