R

E

V N

E

X

T

Recap of Lawrence Abu Hamdan at Tate Modern

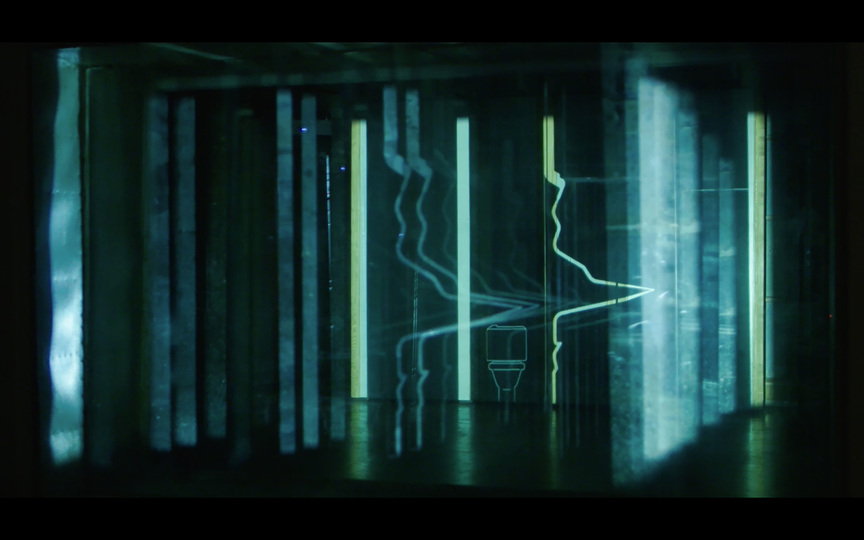

Still image from LAWRENCE ABU HAMDAN’s Walled Unwalled, 2018, single-channel video installation documenting performance: 20 mins. Courtesy Tate Photography.

The cavernous Tanks in the basement of the Tate Modern made an appropriate setting on October 4 for experiencing Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s film installation Walled Unwalled followed by his live sound performance After SFX (both 2018), products of his ongoing research into political terror in authoritarian states. Prior to its conversion to the Tate Modern, the redundant Bankside Power Station featured in a 1995 film adaptation of Richard III as a stand-in for the Tower of London, the most iconic historical prison in the United Kingdom. Abu Hamdan’s body of work often fixes on such coincidences and interrelations as it maps out how mechanisms developed to protect the state from external threats are turned against its citizens.

Walled Unwalled, centered on sound evidence captured through physical barriers, was aptly projected on a semi-transparent wall built across the middle of the gallery. Filmed at Funkhaus, an East Berlin broadcast center that was used by the German Democratic Republic to disseminate propaganda during the Cold War, Walled Unwalled begins with footage of a drummer practicing in one of the recording studios. A roving camera then follows Abu Hamdan as he wanders through Funkhaus, citing examples of Cold-War military technologies and intelligence-gathering tactics that have carried over to contemporary times. He later tells of listening devices intended for use by the United States Army in Iraq that were passed to the Drug Enforcement Administration to catch drug dealers in Oregon.

Abu Hamdan delivers this and other case studies as a deadpan monologue. There is an exhaustive restatement of forensic audio used in the murder trial of Oscar Pistorius that the artist turns into a meditation on the permeability of walls. But it is when he describes the torture of inmates in Syria’s Saydnaya prison that the awful findings of his research hit home. Saydnaya was built based on East German designs to funnel the sounds of the prison to a central point, reinforcing to the inmates a claustrophobic sense of constant surveillance and threat. The film includes text and footage from interviews with former inmates, who appear on screen dramatically obscured in shadow. Based on their testimony, Abu Hamdan attempts to reconstruct the dominant sound they recall from Saydnaya: people being beaten with a length of pipe. The reconstruction of this sound becomes a percussive audio sample that merges into a reprise of the drumming that opens the film.

After SFX followed, with Abu Hamdan walking around the dark gallery, reading a long alphabetical list of seemingly random objects. These are in fact titles of stock sound recordings, or Foley sounds, used in film and television production (“SFX” stands for special effects). Interviewing former inmates of Saydnaya produced an inventory of events, such as bodies being thrown down stairs, that Abu Hamdan tried to match to off-the-shelf sound effects. The artist illustrated how the stock sound effect for a decapitation, created by using a coconut, does not, however, match the sound of actual decapitations, confronting listeners with the reality of the human suffering that his work uncovers. The structure of Abu Hamdan’s performance took on aspects of a DJ session as he mixed the effect tracks, played through loudspeakers sunk into the gallery floor. Some sounds carried startling emotional resonance, like the chimes of an ice cream van, reminiscent of childhood.

Abu Hamdan’s exacting methodology and its practical applications for restorative justice are impressive (his forensic audio studies have been used as legal testimony in human rights cases brought by Amnesty International) but both works here recognize that investigators are always playing catch-up with perpetrators of abuse. At one point in After SFX, for example, the artist purported that since the legal cases revealed how ex-detainees in the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)’s black sites in Europe could describe the prisons through identifying local sound sources, the CIA has reviewed the sites’ locations. Removed from the context of legal evidence, Abu Hamdan’s audio landscapes serve as powerful investigations into the specificities of sound as they relate to memories: some happy and widely relatable, others attesting to unimaginable horrors. Sitting in the dark of the Tate Tanks as the performance wound down, the audience was left to consider what it can truly share as a collective experience.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.