R

E

V N

E

X

T

Hyphenated Spaces: Recap of the 2018 Asian Aotearoa Arts Hui

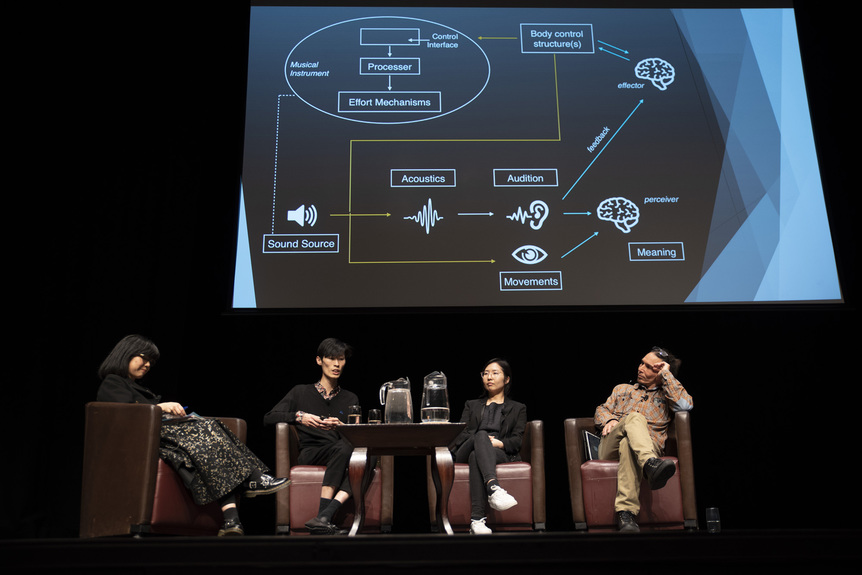

KERRY ANN LEE, YUK KING TAN and VERA MEY in conversation at the 2018 Asian Aotearoa Arts Hui, Massey University Wellington, Wellington, 2018. Photo by John Lake. Courtesy Asian Aotearoa Arts Hui.

The 2018 Asian Aotearoa Arts Hui (AAAH) unfurled energetically and inclusively across Wellington’s central business district throughout September. Art appeared in restaurants, galleries, and on hoardings; walking tours investigated the city; discussions, morning teas, zine workshops, and master classes were staged; blindfolded participants improvised experimental music; and interviews were broadcast from a renegade radio station. One of the concluding events of this expansive programme was a daylong symposium at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, where speakers from a variety of artistic disciplines discussed, celebrated and critiqued “diverse expressions of ‘Asianness’ in Aotearoa in the arts.”

The day opened with a panel about the language used to discuss communities who identify with multiple nationalities. Specifically, the speakers, including curators Balamohan Shingade and Grace Lai, and Chinese program director at Victoria University Yiyan Wang, examined the shift from the use of the term “diasporic” to the more contemporary descriptors “hybrid” and “transnational,” applied to those “occupying the hyphenated spaces” across countries and cultures. Panel chair, curator and writer Emma Ng, suggested that, outside of academic jargon, it is a personal journey for individuals to find the terminology that best articulates their lived experience. The panel also challenged the hegemony of Western art history and its sidelining of Asian New Zealand artists. A counterpoint was offered by Lai, however, who, through the work of ceramicist Wailin Elliott—one of the founders of the influential Auckland Studio Potters Society in the early 1960s—suggested that it can be an artist’s strategic and deliberate choice to circumvent mainstream art histories.

Imbalances of power were also raised in the following panel discussion between artists Yuk King Tan and Luise Fong, and curator Vera Mey. Tan, an Australian-born Chinese-New Zealand artist who lives in Hong Kong (a biography that aptly illustrates the “hyphenated spaces” occupied by many artists, mentioned during the first panel) spoke about the pressure she felt to “represent the whole of Asia” when she was included in exhibitions in New Zealand in the 1990s. When invited to comment on how feminism has informed her work, Mey told the story of undertaking curatorial research in Cambodia for the exhibition “Sunshower: Contemporary Art from Southeast Asia 1980s to Now,” presented at the Mori Art Museum and National Art Center, Tokyo, in 2017. According to Mey, her father traveled with her as a translator, and she suggested that his position as a conduit for her voice could be interpreted as a feminist one.

The next panel, “Making things happen,” shifted slightly in tone to look at the logistics involved in producing headline events such as Auckland’s Diwali Festival, Lantern Festival and Chromacon, an “indie arts festival.” Diwali and the Lantern Festival, staged by the Auckland Council, are two of the largest and most attended cultural events in New Zealand, reflecting the significance of, and attraction to, Asian culture in Aotearoa. Producer and editor Rosabel Tan also introduced Satellites, an itinerant project that stages the work of Asian artists in suburbs around Auckland where cultural experiences are less accessible.

In the first of the afternoon sessions, poet Alison Wong and editor Kirsten Wong shared the moving story of the SS Ventnor, a ship that sank off the coast of Hokianga, on the northern tip of Aotearoa, in 1902. Thirteen people were killed and the exhumed bones of 499 Chinese gold miners, which were being returned to China to be buried with their families, went down with the boat. Local iwi (Māori tribes), Te Roroa and Te Rarawa, collected and buried the bones that washed up on the beach and, 110 years later in 2013, members of the Chinese community organized a special event to pay their respects to their ancestors on the burial site. The sinking of the Ventnor and the subsequent exchange between Māori and Chinese was discussed as an important example of a cross-cultural relationship that is unmediated by, and outside of, the cultural dominance of Pākehā (New Zealanders of European descent).

The subsequent panel also discussed the agency of minority communities in Aotearoa, but in the context of art education. Artists Yona Lee, Simon Kaan, and Jon He, all of whom teach in academic institutions, acknowledged the increasing number of Asian students in tertiary institutions in New Zealand, and the necessity of lecturers of diverse ethnicities to model new pedagogies for this growing cohort of Asian New Zealand graduates.

The panel, “Translation and Mutations,” with Renee Liang, Lynda Chanwai-Earle, and Alice Canton, had the energy and informality required to keep the audience attentive after a day of conversation. Accomplished across playwriting, performance, broadcasting and theater, these women challenged themselves and the audience to “recognize their privilege,” particularly with regards to the hegemony of China when discussing Asia as a whole.

During their conversation I wrote in my notebook, “Should I be writing this article?” Though I am a member of the so-called one-point-five generation, whose parents immigrated to New Zealand from Zimbabwe when I was a child, and I identify with a “hyphenated” cultural identity, as someone of European descent, my experience is not comparable to immigrants of color. The AAAH symposium triggered this kind of self questioning and, because it was staged within New Zealand’s national art gallery and museum, the panelists’ interrogations took on increased resonance: How should those in hegemonic positions check their privilege? Who polices the mainstream of Aotearoa’s national culture? And, following this line of thought, would someone of Asian descent be better suited to write this report for ArtAsiaPacific?

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.