R

E

V N

E

X

T

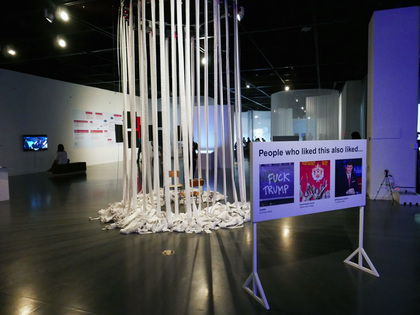

There were a lot of things happening—visually, performatively, conceptually—in the Seoul Mediacity Biennale 2018, and I felt as if I only understood about half of them. Maybe even that is an over-estimation. On the ground floor of Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA)’s Seosomun Main Building alone there was a semi-coherent film based on a screenplay written by an AI that named itself “Benjamin” (by Oscar Sharp and Ross Goodwin); hanging reams of paper printing out live tweets by AI-generated, imaginary people (Mike Tyka); a mobile mushroom cultivation house (the Factory Collective); a lab environment with fish tanks and plants demonstrating something about micro-organisms (Ki-Hyun Jung); a live performance with overhead projections by Tuomas Aleksander Laitinen and Jenni Nurmenniemi (also known as Myriagon); and a corridor of texts, images and videos documenting dance performances by a group of women with disabilities. What alliances and collisions of consciousness had brought all these artworks together?

The curator of Seoul Mediacity was not a 21st-century AI—that can’t be far off for a new-media biennale—but a directorial collective. The group comprised Gibin Hong, the director of the Global Political Economy Institute; Kyung Yong Lim, director of The Book Society; independent curator Jang Un Kim; and dance critic Nam Soo Kim. All are men, as many in the Korean art community were quick to point out when their appointment was announced earlier in the year. It wasn’t a good look for 2018. Nor did it help Mediacity Seoul’s reputation that the fifth member of the collective was SeMA’s director Choi Hyo-jun, until he was suspended from his position in July following a sexual harassment complaint filed by a female museum employee. The collective had earnest intentions in their exhibition, taking up the ancient Athenian philosophical question of what makes “the good life” and its possibilities. Though, it’s notable that no women were invited to participate in those debates in ancient Greece either. Nevertheless, there were 68 practitioners and groups that took part in the conversation at Mediacity—and some of them were women. It wasn’t entirely a bro-ennial, but in large sections of the Biennale, it was pretty close.

Why harp on the gender ratio of the directorial collective and artists when Seoul Mediacity was serving as an expanded platform for progressive activist groups like Greenpeace, Adbusters, and academics like Michel Bauwens, Richard G. Wilkinson and Hyeng Joon Park, whose respective works attempt to imagine better, more equitable futures for humanity? Studies have shown that communities make different, and better, choices when women and men share power and decision-making responsibilities. It’s also a matter of credibility. It’s hard to stomach an intellectual conversation about social equality in the “agora” of an exhibition and all the very serious threats to achieving a “good life” when there’s no recognition of the gaping gender disparity that arguably is part of why humanity continues to barrel along on a course of violent and tragic self-destruction.

Within the exhibition itself were many examples of imaginative, collaborative practices. The “Unmapping Eurasia” project, initiated by Casco Art Institute: Working for the Commons, for instance, presented a first report on the various conversations that had been held as part of the research series, both online and through an installation with re-creations of Gerrit Rietveld’s iconic De Stijl Red and Blue Chairs (1918–23). Zero Space, a sustainable design and zero waste collective based in Seoul’s Dongdaemun area, had set up a temporary co-working space in SeMA to showcase its projects. Wonhwa Yoon and Jeewon Yoon worked together on “Soft Places,” a compilation of videos and recordings. The Welfare State Youth Network • Youthzone Yangcheon is an independent youth organization that presented documentation of their activities and A Young People’s Declaration of Independence (2018). Less interesting was the project by Critical Art Ensemble whose Environmental Triage: An Experiment in Democracy and Necropolitics (2018) asked visitors to vote, à la Hans Haacke, on what should be done to improve Seoul’s water quality. Another relic was the Adbusters group who publish their own bimonthly magazine. Their installation in SeMA, Live Wıthout Dead Time (2018), offered the same pseudo-insightful, postmodernist critiques of mass-media imagery and slogans (“everything is fine, keep shopping”) that made them famous in the 1990s and seem completely facile today.

I appreciated Minja Gu’s banners from her series “23:59:60” (2015/18), of pictures taken during the “leap seconds” added to the world’s clocks by countries around the world. Choi Haneyl created a room full of sculptures that children were allowed to interact with in Home-video #43, A Picnic to Mediacity (2056, 9) (2018). Lee Byoung Jae and Lee Yun Ho, who go by the name Seendosi, presented a room of vehicle-shaped napping equipment, Snooze Express (2018), that wasn’t as functional as I had hoped, but it was entertaining to watch other people trying to contemplate rest in these psychedelic-patterned, fluorescent-painted pieces. Ed Brown’s Brain Burger (2013)—a video of the artist lighting a barbeque grill with his mind—was interesting, but things also got a bit gimmicky with the faux-retail Future Shop (2018) by Namwoo Bae, and images like Aram Bartholl and Nadja Buttendorf’s poster Post Snowden Nails (2016) of micro SD cards glued onto a hand like fake nail extensions. Artists’ imaginations of the post-human condition sometimes resemble contemporary consumer culture a little too closely. This points to one of Mediacity’s central problems: the near absence of political thinking about what it means to have a good life—whether in terms of gender, race, sexuality or class. After all, whatever the future brings will be determined by large groups of people acting, arguing, or acquiescing, en masse.

HG Masters is the editor-at-large of ArtAsiaPacific.

The Seoul Mediacity Biennale 2018 is on view through November 18, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.