R

E

V N

E

X

T

Sharjah Biennial 13: Dakar, "Vive L'Indépendence de L'Eau"

Fishing boats in Fann Hock bay with downtown Dakar in the distance. All photos by HG Masters for ArtAsiaPacific unless stated otherwise.

Water gives life; life needs water. These fundamental realities can easily sound like truisms. But artist Kader Attia managed to invigorate conversations on the subject with renewed environmental and political urgency during the two-day symposium “Vive L’Indépendance de L’Eau” (“Long Live the Independence of Water”) that he organized at the University Cheikh Anta Diop in Dakar, Senegal, and which was the first of four chapters looking at keywords happening this year as part of Sharjah Biennial 13 (SB13). Attia did this by inviting 20-odd speakers who, although they had widely diverse approaches to the topic of water (artistic, literary, architectural, historical, sociological, scientific) and rooted their studies in specific places and histories, created a larger conversation about the interrelation of environmental and cultural sustainability. The independence of water is crucial for its—and our—survival.

So why Senegal? Aside from Attia’s professed fondness for Dakar, water plays a particularly central role in the country. The peninsula on which Dakar is located hooks out into the Atlantic Ocean at the most-western point on continental Africa—a geographical feature that is defining of the Sengalese capital’s industries (trade, fishing) and its history, particularly colonialization beginning in the 15th century and the Atlantic-American slave trade. As literature professor Ibrahima Wane writes in the essay “Water in the History and Imaginary of West Africa” (2017): “Water is a bustling theater of history and the bed of a fertile imagination. Decisive moments in the evolution of humanity have played out on the waves, which serve as the framework for mythic-religious representations. The aquatic world thus forms a bridge between the real and the unreal.”

Kader Attia, organizer of “Vive L’Indépendance de L’Eau” with Sharjah Art Foundation director Hoor al-Qasimi.

Those worlds—and their interconnection—were explored during the first day of the “atelier,” as Attia called it, with a program entitled “Beliefs and Non-Knowledge.” I couldn’t help noticing that when Attia welcomed the assembled crowd on the morning of January 8 at Cheikh Anta Diop University, he was wearing a light blue polo shirt and blue jeans. He stood at the front of a lecture room that he and his team had draped with blue fabrics on a floor covered in blue-hued plastic mats.

The first to present that morning was Rachida Madani, a poet from Tangiers, who read excerpts from her collection of poems written in French, Contes d’Une Tête Tranchée (“Tales of a Severed Head”) that evoke dark eras of political and religious repression in Morocco and the struggles of women in these times. Her stark, strong words captured an environment filled with those fleeing persecution or living on the brink of desperation—themes that would resurface in later discussions in the next two days. Among the poet’s most haunting lines from her first reading were, “Night falls on the ocean / and drowned men guide us . . . / How many of you have died for / having dreamed of another shore / of another dawn / another justice?” Following Madani’s reading, Attia, as a kind of explanation for having poetry included in the program, described poetry itself as having its own properties of “liquidity,” and of flowing like a river—or, I thought, in case of Madani’s poems, like a strong rip tide that pulls you out, suddenly, into deep water.

Following Madani was a completely different kind of presentation, by architecture historian Samia Rab, who compared the approaches to development of port cities such as Sharjah—where she was a longtime resident and professor at the American University of Sharjah—and the North American city of Baltimore. She invoked the work of professor James Wescoat, a historian of waterworks in South Asia cities and his observation that “the right of thirst” for animals, plants and humans is fundamental to Islamic law as a guiding model for good urbanism. Critical of “Vancouverism,” the phenomenon of speculative development of coastlines, Rab advocated for a kind of “porous” architecture that, in an era of rising sea levels, allows water into city rather than forcing cities out onto the water.

Seeing the city from the water is an obsession of the French filmmaker Marcel Dinahet from Rennes, who has been filming places from the “littoral” vantage point of where water meets land. To make his short films, he climbs into the water with a camera in order to capture the perspective above and below the water simultaneously. He showed a video of a thermal plant in Cyprus, which provides energy from the sea to the land, and of the Palace of Westminster in London seen from the Thames, while noting that he is frequently harassed by security officials in the process. “All power exists in relation to water and at the interface between water and land,” he observed, and noted some of the changes that were happening along Dakar’s waterfront, where fisherman were being displaced from the shores for the sake of private developments.

Closing out the morning was French-Algerian poet and “primitive art expert” Pierre Amrouche, who read some of his own poems and then a short text about the mermaid figure of “Mami Wata” from West African folklore that he described as “a symbol of purity and resurrection for the whiteness of her skin.” His generalizing ethnographic text about West African cultures didn’t seem to acknowledge that the figure was obviously not an indigenous name, prompting discontent among the 20-odd audience members who had arrived by that time. One audience member suggested that in fact the figure is probably better associated with the West African manatee whose body shimmers at night in moonlight and is often referred to by the same name.

Ethnography and discussions about the study of traditional beliefs were raised again in detail after the lunch break, beginning with a presentation by Berlin-based Christoph Keller who described his training and first career as a hydrologist. He spoke about his early realization that science was not the neutral form of knowledge he’d been led to believe: that it sees the world from the lens of use value and excludes traditional myths and rituals as part of a larger colonial project. “You feel the lack of magic in modern culture—there is a missing depth,” Keller reflected. While acknowledging that great feats of engineering and scientific advancement, like the Itaipu dam on the Paraná River in Brazil, the Aswan dam in Egypt or Three Gorges dam in China, have allowed countries independence and modernization, Keller noted they have also created a new dependence on what he called “technological colonialism,” and a universal worldview that disregards local and traditional customs. His film Anarcheology (2014) attempts to illustrate the gulf between these forms of knowledge. The silent video begins with a photograph of the Manaus-Iranduba Bridge spanning the Amazon, and embarks on a voyage of reflection about the boundaries between written and oral forms of culture, stemming from a trip up the Amazon and his encounter with the beliefs of the Yanomami people.

The threads of Keller’s interests were picked up by Senegalese philosopher Ibrahima Sow, who explained the breadth of the divination practices in Senegal. “Despite Islamization, there is an animist bedrock,” he began, and illustrated how the various practices of maraboutage (sorcery and magic practices) incorporate elements of Islamic beliefs. He illustrated, for example, divining techniques that use shells from the Maldives whose shapes can resemble anatomical parts, including eyes and genitals, and Sow invited an actual interpreter of signs to demonstrate sand-writing and the practice of using a young child to interpret reflections from a bowl of water.

The idea of “technical colonialism” and preserving traditional forms of knowledge returned in the presentation of Yasmine Terki, an architect from Algiers who specializes in the clay and earthen architecture of Ksour settlements, found in areas just north of the Sahara desert. She noted that this form of clay architecture, though prevalent in arid climates, is dependent on water for binding the sand particles into a solid construction material. She runs the Centre Algérien du Patrimoine Culturel Bâti en Terre (Capterre) and explained how the organization has tried to improve the reputation of traditional forms of building. Her argument was that using indigenous building techniques is a way out of dependence on the neocolonial economic systems that require imported steel, concrete and other materials—ones that can’t be recycled like clay and require additional energy like air-conditioning and heating, rather than being self-regulating. Like Samia Rab earlier in the day, Terki was looking at the wisdom of pre-modern builders who had worked in concert with their environs, rather than against them.

At the end of the day, Rachida Madani returned with more poems, these ones about dunes and sand. Like Terki’s presentation, Madani’s poems elegantly bridged the similarities between sand and water, desert and ocean. The day’s final speaker returned the conversation to Senegal. Ibrahim Wane looked at the motif of the boat in Senegal’s music, from the songs of fishermen where, he observed, “tradition and memory are preserved in sound” in the fishermen’s syncretic forms of Islamic beliefs and pre-Islamic folklore. Wane also noted that the people in central Senegal believe their ancestors were the gift of the sea, carried inland by great waves. But Wane noted in Senegalese history the “ambivalence of water: as a source of life but also of tragedy, like the slave trade,” mentioning the exile of Senegalese resistance leaders, to Gabon, in 1875 on French ships. Those final words resonated on our walk back to our hotel along the corniche, where hundreds of people were exercising and playing on the beach, and just 2,800 kilometers beyond the horizon to the southwest lies South America.

Day 2

Things got off to a slower start on the second day, which had been given a more convoluted title: “Everyday Life’s Political Control of Liquidity.” Activist and musicologist Kemi Bassene, one of the co-founders of the journal Afrikadaa, read a text about water-management policies, colonial power structures and the replication of master-slave dynamics in the current exploitation of natural resources. This was followed by Haidar el-Ali, who is a filmmaker and also Senegal’s former Minister of the Environment and Sustainable Development (2012–14); he spoke about his efforts to convince communities to replant mangroves to prevent seawater inundating their rice fields and to protect manatee habitats. El-Ali noted that agricultural investment is less expensive and gives longer-term financial rewards, and set forth an argument similar to that of Yasmine Terki’s the previous day, in that communities need to create their own strategies for independence and sustainability.

The shores of the art world were never too far off. Attia next screened Hito Steyerl’s video Liquidity Inc. (2014), which humorously looks at metaphors of water connected to the financial industry (like “liquidity”) and ideas of indestructibility, beginning with the famous Bruce Lee quote: “Be formless and shapeless, like water.” The video centers on Vietnamese-born refugee Jacob Wood, who was rescued in Operation Babylift in 1975 and grew up in southern California. When he gets laid off from his job as a financial advisor after Lehman Brothers goes bankrupt in 2008, Wood changes professions and trains as a mixed-martial arts fighter and wrestling-match host. It’s far from Steyerl’s best video and features some tediously repetitious sections, and ends with the artist “drowning” in her own work and deadlines—as a kind of personalized counterpoint to the financial discourse it parodies.

Drowning—and specifically the tens of thousands of deaths that have happened in the Mediterranean Sea in recent years—became the subject of the following presentations. Curators and art theorists, Aliocha Imhoff and Kantuta Quirós, who founded a curatorial platform “Le Peuple Qui Manque,” explained the origins of their organization by citing Yael Bartana’s film trilogy “And Europe Will Be Stunned” (2007–11). The works are about the imagined return of Jews to Poland and the Detroit electronic music group Drexciya, whose 1997 album The Quest imagines the children of pregnant slaves thrown into the Atlantic forming a new civilization under the ocean. Imhoff and Quirós attempted to explain their upcoming project to hold a “Migrant Constituent Assembly” at the Centre Pompidou in Paris on January 28 and 29, in which they and invited guests—including Kader Attia and roughly 30 other artists—will attempt to write a constitution for the people who have died in their journey toward Europe. Based on simulation methodologies like Bruno Latour’s staged rehearsal of the Paris COP21 conference, the proposition is provocative in attempting to speak on behalf of the deceased and Imhoff and Quirós’s presentation sparked a confused debate about its purpose and ethics. Imhoff obstinately replied that such confusion was part of their intended statement: that it is meant to be seen as “a square circle.”

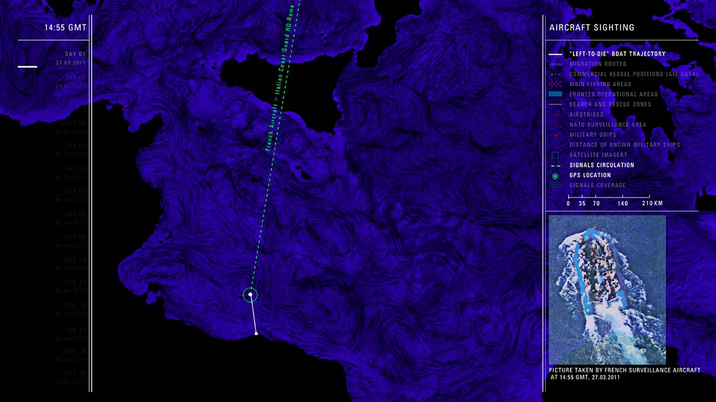

Quite in contrast to the speculative proposal of Imhoff and Quirós was the analytic duo Lorenzo Pezzani and Charles Heller, who are graduates of the Forsenic Architecture agency founded by Eyal Weizman at Goldsmiths and are also scheduled participants in the “Migrant Constituent Assembly.” They screened their film Liquid Traces: The Left-to-Die Boat Case (2014), which takes the particular case of a boat full of migrants that left Libya and headed for the Italian coast. Using NATO’s own surveillance technologies, it shows how military ships had deliberately let the boat drift resulting in the death of most of its passengers—or as Heller put it: how NATO “murdered them without touching their bodies.” Pezzani and Heller were joined by a leading researcher on African migration, Papa Demba Fall, who broke the sudden descent into Eurocentricism by injecting some larger perspective on migration. He noted that, in fact, most migration in Africa is around the continent itself, not into Europe, with 61 million people annually going “south to south” not “south to north.” He also sought to break the perception that migration is solely motivated by economic reasons. He explained that in many Senegalese communities, moving away and surviving on one’s own is seen as a requisite right of passage, a means of proving oneself. And, as elsewhere in the world, he noted, young people move to escape social pressures and earn a bit of independence, to have their own possessions and not to labor solely for the community or family leader.

More resistance to the creeping Eurocentrism of the day’s conversation came in the presentation of postcolonial literary scholar Seloua Luste Boulbina and Bado Ndoye, a philosopher at Cheikh Anta Diop University. They engaged with ideas of decolonization and urged a further decolonization of the mind, in the wake of independence. Observing that the “price of raw materials is still being set in London or Paris,” they further pressed on European perspectives of "humans of the south are the raw materials of today”—in what I understood as a reference to Imhoff and Quirós’s idea of drafting a “Migrant Constituent Assembly” in the heart of Paris, on behalf of those who were barred from entering Europe.

Reaching back to the themes of the first day, curator Nadine Bilong talked about the Ngondo celebration of the Sawa people in Douala, Cameroon, during the December dry season. She disputed the use of the term “Mami Wata,” introduced by Pierre Amrouche, saying it was not authentic to Africa nor one that is used by initiated people. Instead she talked about the figure of Jengu, who in Sawa rituals is a man of strength, and she discussed how the annual rituals could be used as a way of rehabilitating communities and aquatic sustainability, with the integration of cultural values, environmental concerns and their economies—especially for craftsmen and tailors who rely on the annual rituals for business. She finished by asking Kader Attia if the point of the symposium wasn’t the “independence of water” but about the “independence of the people of the water.”

Attia replied by asking more questions: What kind of “dependence” do we have after “independence”? The purchasing of concrete, for instance, he said, sends money back to Europe or to multinational corporations. He noted that these are larger issues as governments everywhere, including in Europe and the United States, have sold the best resources—including water—to private corporations to be packaged and re-sold to people. This two-day symposium, Attia said, was part of this struggle for new forms of independence, mentally as well as economically, as well as an attempt to find new ways of transferring knowledge in the setting of an “atelier” where we all worked together.

In conclusion was a presentation by Malick Diouf, professor at the University Institute of Fisheries and Aquaculture at Université Cheikh Anta Diop, who highlighted activities of the Serer people in the Saloum Delta Region, south of Dakar. Diouf is also worried about the demise of their traditional aquaculture—particularly the gathering of mollusks from tidal areas—that was impacting the larger culture of groups. He introduced a group of Serer performers who were keeping their own traditions alive and explained their songs, from welcome greetings to tributes to the water and mountains and a farewell song that no one seemed to want to end. After thinking about water and culture for two days, their fates seemed inextricably linked, making the case that rescuing one or the other from the forces of neocolonialism requires a more holistic way about thinking about sustainability, involving people and their environments. As humans, we remain dependent on this resource, one that we must allow to be independent and to flow freely.

HG Masters is editor at large of ArtAsiaPacific.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.