R

E

V N

E

X

T

KHADIM ALI, Standing Flames, 2019, from “Flowers of Evil,” acrylic, industrial paints, Dutch metal golf leaf on MDF, 1,785 × 539 cm. All photos by HG Masters for ArtAsiaPacific, unless otherwise stated.

The title of Sharjah Biennial 14 (SB14), “Leaving the Echo Chamber,” set the bar high for the three curators selected for the 2019 edition. The phenomenon of the echo chamber is a structural one that entails people having their world view reinforced by the like-minded community they choose to have around them. It is a problem of the audience—a perennial challenge for many arts organizations—and how to reach new publics, how to engage with them, and possibly how to impact them. How then can a biennial engage beyond the echo chamber of the art world and its cultural classes?

Perhaps this wish to imagine conversations between diverse publics was the logic behind commissioning three curators to create three separate exhibition platforms in close proximity to one another, under the umbrella of SB14. Each platform was notably distinctive. Claire Tancons’s section “Look for Me All Around You” had a strong performative bent. Many of the artworks by the 27 artists look at themes relating to diasporas (particularly in the context of the Gulf, Africa, and the Americas) in what the curator calls an “open platform of migrant images and fugitive forms.” Featuring many Beirut-, London-, and North America-based artists, Omar Kholeif’s “Making New Time” examined the new material cultures produced by rapid technological development and their impacts on the human body and conceptions of history. With subtle thematic links to each of the two other sections, Zoe Butt’s “Journey Beyond the Arrow” delved into the “movement of humanity” and the tools, technology, and beliefs that undergird “voluntary and involuntary patterns of discovery, conquest, witness and exile across land and sea” through the works of 27 artists who have ties to Asia or the Asia-Pacific region.

The most challenging of the three platforms in thematic and experiential terms was Tancons’s “Look for Me All Around You,” which takes its title from pan-African political leader Marcus Garvey’s 1925 address at an Atlanta prison (the rest of Garvey’s sentence is “with God’s grace, I shall come and bring with me countless millions of black slaves who have died in America and the West Indies and the millions in Africa to aid you in the fight for Liberty, Freedom and Life.”). The live, performative components of the exhibition—such as Meshac Gaba’s parade of headdresses woven to resemble iconic buildings in the United Arab Emirates; Ulrik López’s restaging in syncretic Caribbean styles of a ballet celebrating a famous chess match; and Mohau Modisakeng’s evocation of African slave trade histories that unfolded in a processional mis-en-scène down the beach in Kalba—were all highlights of the opening week program. Though they were recorded, or will be partly restaged, and will each be represented in different manners in the exhibition, the initial performance of these events for the professional art class that gathered for SB14’s opening did make the struggle to leave the echo chamber apparent.

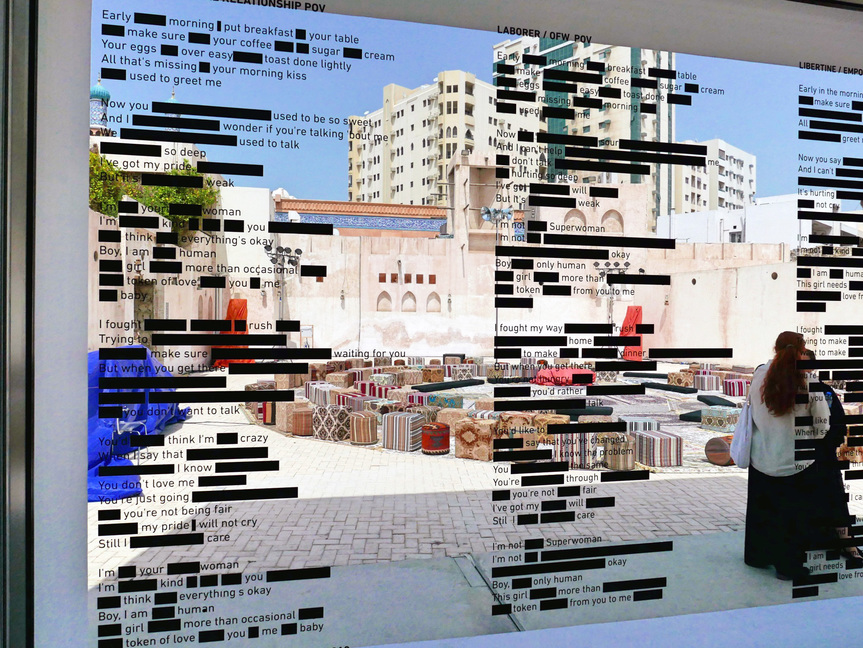

Other works from Tancons’s platform engaged consciously with performativity and temporality in the exhibition context. Eisa Jocson’s Passion of Darna (2019) is an interactive installation that allowed visitors to sing along to a Filipino rendition of the song “I Am Not a Superwoman.” Participants’ voices were broadcast from disco-ball-style speakers in the courtyard outside. Caline Aoun’s Time Travel (2019) is a nightly projection of the sunset in Lebanon on the courtyard walls of Al-Mureijah Square. The hazy image is created by four projectors spinning at 375 rotations per minute, effectively showing images at 25-frames per second, like an analogue piece of technology. Similarly, Wu Tsang’s One emerging from a point of view (2019) was only played in the dark, after the last call to prayer, because it was staged in an open courtyard. The film, about a refugee and a photojournalist who cross paths on the Greek island of Lesbos, was beautifully shot and staged with two overlapping channels. Allora & Calzadilla have an audio and laser work that is activated at noon every day. Hannah Black and Ebba Fransén Waldhör’s charming Suntitled (2019) is a cubic, sky-blue hut perforated with little smiley faces that allow sunlight into the room; when a smiley face aligns with the surface of a crudely anthropomorphic asphalt sculpture, a recorded monologue begins to play. Between the works that are only activated once, or only at noon, after dark, or at shifting times throughout the day, Tancons re-imagined and marked many kinds of time and space within the exhibition.

Omar Kholeif’s exhibition platform, “Making New Time,” was billed as “a provocation,” and a challenge to slow down and “‘experience’ the experience,” while also looking at how technological culture has changed our relationship to our bodies. Reflecting those two themes, Kholeif selected works by several painters to show in a wing of the Sharjah Art Museum. On view were 1960s abstractions by Anwar Jalal Shemza, who challenged the orthodoxy of both Islamic and European modernist aesthetics by combining them; Lubaina Himid’s paintings and installations about slavery; Turkish opera singer Semiha Berksoy’s figurative canvases; portraits by Marwan; and the canvases, both surreally figurative and abstract, of Hugette Caland, shown alongside her painted kaftans and smocks, some created with designer Pierre Cardin. Shezad Dawood’s VR work and terrazzo-wallpapered installation Encroachments (2019) takes viewers on a journey through the oldest bookstore in Lahore, a video arcade (where you can choose which anti-Soviet game to play), and the Richard Neutra-designed former US Embassy in Lahore. Similarly bridging figurative painting with an interest in new technology is Ian Cheng’s trilogy of computer-generated simulations, “Emissaries” (2015–17). Scenes of rampaging figures burning and killing one another (at the times I saw it) were shown on a large-scale screen in the plaza outside the museum, next to Bait al-Serkal.

Inside the Bait al-Serkal building, I was most engaged by Marwa Arsanios’s Who is afraid of ideology? Part 1 (2017) and Part 2 (2019)—video documentaries about Kurdish autonomous movements. The first looks at a group teaching themselves how to survive without men in a remote area of Turkey, while the second features women in the village of Jinwar in northern Syria, where they happily expelled all the men. Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s video and installation Once Removed (2019) features him—almost like a standing television news anchor on CNN—interviewing 31-year-old writer and historian Bassel Abi Chahine about his archive of photographs and documents related to Druze militias from the Lebanese Civil Wars. The subject’s extensive knowledge of a conflict before his birth comes, Chahine believes, from his past life as a soldier who died in 1984. Bait al-Serkal’s courtyard was empty, except for Pamela Rosenkranz’s Healer (2019), an “algorithmic snake that lives, breathes, sleeps and dreams in the sun-drenched courtyard.” Even though, or especially because, it is a mechanical device, to see it writhe in its intermittent, performative spasms induces a strange mix of the uncanny, horrific, and comedic.

One work from Kholeif’s platform that I remain conflicted about is Alfredo Jaar’s installation 33 Women (2014–19). In a large gallery space, sets of lights on tripods illuminated small, framed, black-and-white portraits of women, with no accompanying labels that identify them. Instead, there’s a book with the photos and their biographies, so you have to match image with text, effectively slowing down the process of viewing. The women Jaar highlights are activists, such as Iranian human-rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, Vietnamese anti-corruption blogger Ta Phong Tan, and Egyptian writer and anti-female genital mutilation activist Nawal el-Saadawi. On paper, they all sound like extraordinary people, but I wondered about the dynamic of spectators being asked to look intensely at women’s faces—for all the ways in which this mimics, or intensifies, the focus on women’s physical appearance as a stand-in for their actions. My experience of the piece was also clouded by the absence of guide books on the first day and the fact that members of the press were told we were not allowed to view the binders dedicated to each woman that were sitting on a shelf in plain sight behind a desk outside the installation. I left my name and email address on a form saying I was interested in seeing the book and the binders, and someone from Sharjah Art Foundation wrote to me cheerfully later in the day saying I could come back and receive a copy—a form of screening, I gathered. I’m not sure whether it was because of the depictions of Iranian or Yemeni activists, or just activism in general that the project was treated as potentially sensitive material. One of the women in the photos is Saudi driving activist Loujain al-Hathloul, who was arrested in 2018, tortured, and who remains a political prisoner. At the same time of SB14’s opening in mid-March, she and fellow activists were secretly being tried by the Saudi regime for “undermining state security.”

Zoe Butt’s “Journey Beyond the Arrow” didn’t shy from revisiting the legacy of horrific historical events. Phan Thao Nguyen’s three-channel video Mute Grain (2019) and related silk paintings revisit the period of Japanese Occupation in Asia, specifically the 1945 Red River Delta famine, which saw the deaths of more than two million people. Meiro Koizumi’s three-channel film similarly re-examines Japanese imperialism, with a recording of a former soldier (now quite elderly and suffering from dementia) recounting his participation in war crimes. The scenes of testimony, which are almost unbearable to watch, are then re-enacted by contemporary Japanese youth in an attempt to achieve collective, societal responsibility. Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s four-channel video and accompanying images, The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019), about the Senegalese-Vietnamese community, was beautifully filmed, and re-imagined events of a doubly-marginalized community created by the wars imperial France was fighting with African soldiers in Indochina. Jompet Kuswidananto’s installation Keroncong Concordia (2019), of a bird-shaped chandelier crashed into the ground, references the mixed-heritage and fragmentation of the “intercolonial” community (Indo-European-African-Dutch-Indonesian) that gathered around the music style of a Bandung nightclub. Similarly grandiose in its theatricality is filmmaker Kidlat Tahimik’s gallery-filling narrative installation composed of carved wooden sculptures and rattan figures that image an Ifugao indigenous tribe’s god, Inhabian, protecting the community against a tsunami-wave embodied in the avatar of Marilyn Monroe.

Khadim Ali had what was almost a solo exhibition, with a massive mural Flowers of Evil (2019) on the wall of the Emirates Fine Arts Society building, depicting a winged version of Rustam from the Shahnameh, who doubles as a hero of Taliban propaganda. Ali also presented a giant iron sculpture of a bomb inside a courtyard, and had nearly half the wing of the Sharjah Art Museum for his sound installation, tapestry works, and miniature paintings. I didn’t understand the necessity of having Xu Zhen’s project “The Starving of Sudan” (2008) in the exhibition. The series of photographs documents a performance at Beijing’s Long March Space, for which the artist hired a boy from Guinea whose mother had migrated to Guangzhou, and created a backdrop with a stuffed vulture reminiscent of a controversial 1994 Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph by Kevin Carter. The work’s setting is intended to pile outrage onto outrage, in a way that may have been provocative originally—yes, a Chinese contemporary artist can be as exploitative as an American photojournalist—but today seems more offensive and less interesting in its restaging.

There were other puzzling elements to SB14. As a collective whole, “Leaving the Echo Chamber” projected a muddled sense of the main subject. In their joint statement, the curators write: “In popular culture, the ‘echo chamber’ is a moniker for circuitous news media and their attendant feeds, which are reinforced by a closed network controlled and governed by private sources, governments and corporations.” This is incorrect and a strange contortion. The “echo chamber” is not the news media “governed” by governments and their private, corporate arms—that is propaganda. So it’s even more perplexing that the curatorial statement goes on to say: “Leaving the Echo Chamber does not propose a ‘how to leave’ this context, but rather [. . .] how one might renegotiate the shape, form and function of this chamber in order to move towards a multiplying of the echoes within, such vibrations representing the vast forms of human production—its rituals, beliefs and customs.” In other words, “Leaving the Echo Chamber” is not about leaving; it is about making more echoes. Didn’t the curators describe the “echo chamber” as a contemporary form of propaganda? (The same statement also says “the echo chamber could be construed as a modern-day Faraday cage,” which is just a chaotic mixing of metaphors.)

Ultimately, the “echoes” of the metaphorical “echo chamber” should be distinguished from the “resonance” that many of the artworks in SB14 had with historical topics from the black Atlantic, African, and Caribbean diasporas, to the contemporary Arab world, and the legacies of colonialism in Southeast Asia. Ho Tzu Nyen’s “The Critical Dictionary for Southeast Asia” (2012– ) is an ongoing project about finding what links a region that has no obvious religious, political, or linguistic ties, and explores connections—from bronze musical instruments like gongs, to tigers, and cultures of corruption—that cut across history and cultures in narrow but new ways. To that end, it’s not more metaphors for decolonialization that are needed, but actual structural changes to break free of all our echo chambers.

HG Masters is the deputy editor and deputy publisher of ArtAsiaPacific.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.