R

E

V N

E

X

T

In RANDA MAROUFI’s film Le Park (2015), the artist poses men and women in a frozen tableau within an abandoned Casablanca amusement park. Courtesy the artist.

The second part of Sharjah Biennial 13’s Act II in Beirut transitioned from the off-site project about “the culinary” on October 14 and 15, to a more general program of conversations, screenings and performances over the next week about a host of political and environmental concerns, in the manner of past editions of Ashkal Alwan’s roughly biennial Home Works festival. Two substantial exhibitions and a special project anchored the activities, where the political and environmental topics that have animated so much of the art created and displayed in the 2017 Sharjah Biennial’s many incarnations returned, albeit from a series of increasingly resigned and even depressed perspectives.

The first of these that I saw was the special project by Akira Takayama held at Zico House, which is a unique institution—a family home between Downtown Beirut and Hamra that Moustapha Yamouth (also known as Zico) converted into an alternative art space in the 1990s after the civil wars had ended, as a venue to host performances and friends’ art shows. The informal spirit of the original concept and its ’90s ethos live on today—particularly in a project titled “Beirut Heterotopia,” in a nod to Michel Foucault’s oft-cited concept about “sites and conditions of perceived otherness.” Responding to his time in Lebanon, Takayama invited five writers to narrate the stories of individual families, and then set designers or architects conceived the room as a spatial experience (the artist has executed iterations of the project in Asia and Europe since 2013). You could listen to the stories by scanning a QR code on your smartphone or read the tales in a booklet.

Zico House hosted the multimedia project “Beirut Heterotopia” by AKIRA TAKAYAMA. A series of rooms each told the story of a family, with an accompanying narrative that you could listen to on your smartphone. For instance, in the first room, all the furniture was piled in the middle to accompany the story Nineteen Ninety One, written by Mirene Arsanios. All photos by HG Masters for ArtAsiaPacific unless otherwise stated.

In the first room, all of the furniture was piled in the middle, paired with the story Nineteen Ninety One, written by Mirene Arsanios, about a family living outside the city in a “hilly pinewood region called Monte Verde,” with a teenage daughter, absent father, depressed mother and abused Sri Lankan housekeeper getting by during a transitional period of the country, before things fall apart and they move out of the house. Downstairs, in a salon that had a giant lime tree emerging from a table covered by red cloth, Raafat Majzoub’s tale was about a family where “secrets are the man of the house,” as a mother tries not to contend with her son’s homosexuality. A fifth room, whose story Double U, Not You You, by Jessika Khazrik, is set in the near future, and features an automated housekeeper called 2ew-a 2ew-a, with a room littered with confetti and the phrase “its ok” in plastic letters on the walls. I generally liked the experimental nature of the project, but didn’t find any of the settings to be truly transformative, in the way that many artists, like Mike Nelson or the duo Justin Lowe and Jonah Freeman, have built installations that conjure up characters and scenarios; I suspect that comes with more time and development between the writers and set designers. As I have felt with other parts of the Sharjah Biennial 13, such as certain projects in the Istanbul chapter (which had also been hosted in an old building with creaky infrastructure), the works were still in formation or like the first attempts to use certain mediums or formats. You could see an artist’s potential, and even like the idea behind the work, but still walk away unconvinced about the substance of the project or experience.

The production values were stronger in the two formal exhibitions. A former Ottoman-Venetian home is now the Sursock Museum—after major renovations a few years ago, its cavernous underground gallery offers space for large-scale contemporary art. There, Reem Fadda had curated the group exhibition “Fruit of Sleep,” based on Egyptian journalist and writer Haytham el-Wardany’s The Book of Sleep (2017), which considers the person sleeping not as a passive, unconscious figure but an active agent of digestion (of food, images, information) and dreaming (of revolutions, perhaps). According to Fadda, her exhibition picked up metaphorically from Zeynep Öz’s project in Istanbul, titled “Bahar” (Turkish for “spring”), where many artists had dealt with the notion of hibernation or dormancy like seeds, and linked to “the culinary” through commonalities between sleep and digestion, where potential energy is accrued.

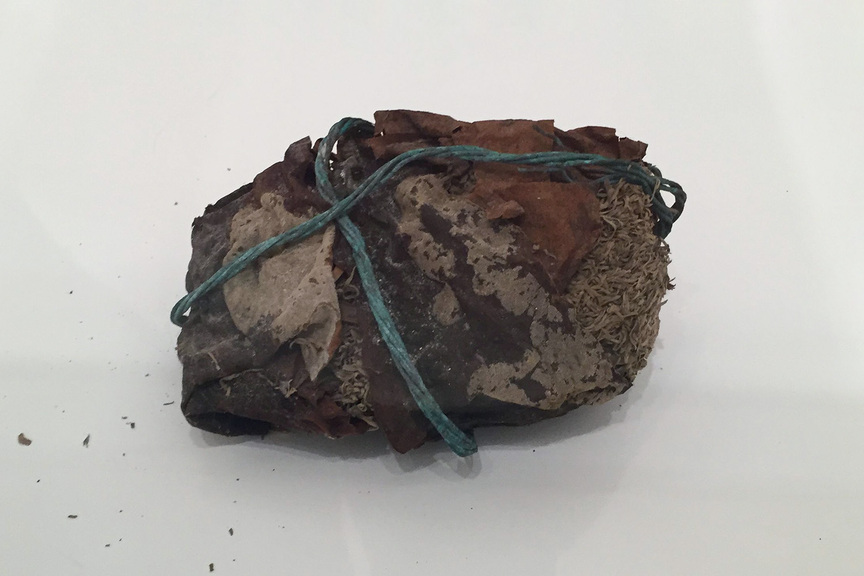

Back in the realm of the senses, even in the cavernous space, I gravitated to Khalil el-Ghrib’s small, organic sculptures that were in various states of decay and decomposition, and have titles like Three Algae with String and Two Stones with Imprints (both 2017). It’s hard to describe what they look like as individual objects, but imagine going for a walk on the outskirts of a city where construction debris, trash, bits of food and nature are entwined in an entropic battle, and picking up curious-looking things wrapped in organic matter. As objects, el-Ghrib’s delicate sculptures inhabit the tiniest threshold between found objects and something “made” with intention—and in that way, exist in a dimension that resembles the state between sleep and wakefulness, consciousness and its submersion. In a similar vein of the artificial-natural dialectic, Tamara Barrage’s silicone and resin sculptures glowed in a darkened room like organic, alien forms, equal parts sci-fi and microscopic vision.

Many works were caught between two worlds, sometimes in political and geographical ways. Forensic Architecture’s project Ground Truth (2016), for instance, looked at the contested status of land in the occupied territories of the West Bank, where Israeli authorities are continuously bulldozing Palestinian-Bedouin villages, including a village named Al-Araqib, which has been demolished more than 116 times since the 1960s as part of the Israeli state’s efforts to eradicate indigenous populations, in this case using “forestation” techniques to claim grazing land as state property. Praneet Soi’s display of tiles made in collaboration with Kashmiri artisans mines the terrains between fine art and craft, as well as the heritage of the region contested by India and Pakistan. In Dubai, Rami Farook sets up goal posts in the city’s in-between spaces, turning them into impromptu sports fields, and documents the games that are played in photographs.

One of the centerpieces of the exhibition was the Sigil architecture collective’s project Electric Resistance – Monument to a Destroyed Windmill (2017), a circular arrangement of 24 electrical cells made with engraved copper and aluminum plates, all submerged in an electrolyte solution to generate power. It visualizes the story of the windmill constructed in the Damascus suburb of Arbin by Sigil, along with photojournalist and architect Yaseen al-Bushy and a blacksmith who goes by the name Abu Ali al-Kalamouni for security purposes. The contraption had powered an underground field hospital until it was destroyed by an air raid. The sculpture’s cells work at a smaller scale, and power a tiny light—with all the bright metaphors that spring from that.

The second major exhibition was at the Beirut Art Center (BAC), next to Ashkal Alwan, that played host to an exhibition curated by Hicham Khalidi with Natasha Hoare that also looked at transition or liminal spaces, in a more explicit and geopolitical sense. The show was called “An Unpredictable Expression of Human Potential”—named from historian Joshua Rothman’s take on culture critic Raymond Williams’s reading of culture as “organic, heterogeneous and disobedient.” The curators zeroed in on the conditions of youth, particularly among the lower classes in Europe and the Mediterranean region, and the kinds of personal tragedies that spring from the conditions of a deeply violent and inequitable time. I was interested to finally watch Eric Baudelaire’s 99-minute film Also Known as Jihadi (2017), which reveals a young man’s journey from Paris to Syria—via the “jihadi highway,” through Istanbul and then southeastern Turkey—all through judicial reports. Baudelaire also films much of the character’s journey, from the landscapes around the Parisian airports, to the roads of southeastern Turkey and later Spain that he took to and from Syria, as well as the waxing and waning of his (and his friends’) enthusiasm for life as insurgent fighters.

PRANEET SOI’s display of tiles made in collaboration with artisans from Kumartuli in North Kolkata and Srinagar in Kashmir for Srinagar I (2014–15).

SIGIL architecture collective’s project Electric Resistance – Monument to a Destroyed Windmill (2017), a circular arrangement of 24 electrical cells made with engraved copper and aluminum plates in water that visualizes the story of the windmill constructed in the Damascus suburb to power an underground field hospital.

There were several other notable video works, such as Laura Henno’s video Koropa (2016) that captures at great length a young boy piloting a boat at night; in later shots, we glean that he is positioned by smugglers as the “captain” of a boat ferrying migrants in the Comoros Islands from Anjouan to the French territory of Mayotte because he is too young to be arrested. Life in Morocco among young people is recreated in Randa Maroufi’s film Le Park (2015), in which the artist poses men and women in a frozen tableau within an abandoned Casablanca amusement park, evoking their social lives in poignant vignettes. Eric van Hove’s video from his Mahjouba Initiative (2016), filmed by Meriem Abid, depicts the story of intrepid young Moroccan craftsmen who take their skills that have little market value and put them toward recreating an electric moped piece by piece—constructing a wood and leather version that is beautiful and functional.

The aesthetics of many projects were memorable, beginning with Jesse Darling’s pair of sphinx-like, blue-faced figures wearing hoodies that greet visitors to the BAC. Upstairs, a room-sized installation by Korean-born Sara Sejin Chang (Sara van der Heide, in her Dutch name), Mother Mountain Institute (2017), features red and yellow spheres orbiting one another, set to a soundtrack of conversations with mothers who were forced to abandon their children for adoption. Dala Nasser made an assemblage-painting called David Adjaye’s Trash (2015) based on materials she gathered from the architect’s USD 100 million Aishti shopping mall and art foundation, just outside the city—which was being constructed when Beirut was experiencing its trash crisis, and illustrates all the neoliberal contradictions that lie in starchitecture and private art spaces that seem to accompany total degradation of public space and the environment.

Throughout the presentation, punk elements and simmering resentment were channeled into highly socialized forms. Mohamed Bourouissa’s project Si Di Kubi (2017), for instance, was a recording-studio installation where you could listen to the albums—on car-stereo CD-players, no less—being produced over the course of the exhibition by various groups of collaborators in different languages and covering multitudinous social themes. It proposed a DIY distribution network for the collaboratively produced music, which I found unobjectionably nostalgic in recalling the days of ripping CDs for friends. Say what you will about the ’90s—whether it was Michel Foucault’s popularity, the various post-1989 political détentes once the Cold War ended, or mix-CDs and hip-hop—there were potentials in that decade that look almost utopian compared to the era of “David Adjaye’s trash” that we, the residents of Al-Araqib village, and the youth “also known as Jihadi” now collectively inhabit 20 years later. Which way to the nearest heterotopia?

HG Masters is editor at large of ArtAsiaPacific.

“Beirut Heterotopia” was on view at Zico House, Beirut, from October 14 to 22, 2017.

“Fruit of Sleep” is on view at Sursock Museum, Beirut, until December 31, 2017.

Daily screenings for “An Unpredictable Expression of Human Potential” take place at Beirut Art Center until January 19, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.