-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

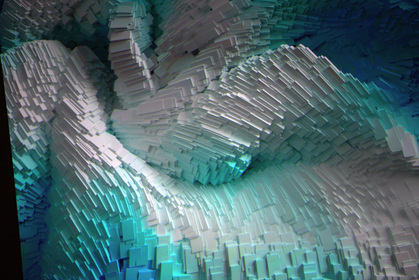

Installation view of “40 Years of Humanizing Technology,” at Design Society, Shenzhen, 2019–20. Courtesy Design Society.

In less than a century, the digital revolution has fundamentally and radically changed our way of life. With the rise of artificial intelligence, genetic modification, and other technological applications, timely debates over their ethical and ontological implications have arisen. The exhibition “40 Years of Humanizing Technology” at Shenzhen’s Design Society took stock of our present tech-focused reality, featuring 28 media artists and collectives. Co-curated by artist and academic Qiu Zhijie and Martin Honzik, senior director of Ars Electronica, the exhibition traced the global dynamics of technological advancement while exploring the close interrelations between humans and machines.

Some of the works collapse the separation between nature and technology. Near the entrance, Quayola’s Remains (2018), a pair of light boxes over several meters tall, pixelates and recomposes images of a wintry forest via computing algorithms, resulting in a hybrid of natural landscapes and digital graphics. In a dimly lit room nearby, more than 400 glasses of water placed on shelves seemed to magically issue clear, crisp sounds that rhythmically resounded throughout the space. For Chijikinkutsu (2013–19), Nelo Akamatsu set up a temporary magnetic field with copper coils, attracting the magnetized sewing needles floating within the tumblers; the Zen soundscape derives from the needles hitting the glass. Chijikinkutsu is a portmanteau of chijiki (geomagnetism) and suikinkutsu, a Japanese Edo-period sound-art practice for traditional gardens whereby objects were used to magnify and alter natural sounds. Akamatsu’s installation thus evokes natural surrounds while attesting to humanity’s ancient ways of interacting with the environment. In Quadrature’s Positions of the Unknown (2017), meanwhile, the technological imaginary extends beyond the earthly realm into outer space. Arrayed in a straight line, the 52 machines equipped with pointy needles track, in real time, mysterious Earth-orbiting satellites that are not officially recognized by any government, establishing a silent dialogue between tangible and the unknowable space.

Other exhibits confronted the ways that technology acts on the body. The Art of Deception (2015), for instance, is based on a series of experiments with animal organs conducted by bio-artists Isaac Monté and Toby Kiers. Hanging in empty glass jars are 21 pigs’ hearts that have been decellularized and repopulated with new stem cells, transforming them into grotesque sculptures with what are hardly recognizable as organic material. For Human X Shark (2017), Ai Hasegawa and a team of researchers developed a scent that attracts male sharks underwater. Displayed alongside vials of the product was a video documenting a group of sharks swimming up to a perfumed Hasegawa during a dive. For the artist, the experiment has a deeper feminist significance: Hasegawa’s disguise as a female shark symbolizes a “wild-natured, strong woman fully utilizing future technology.”

Refik Anadol’s newly commissioned video installation anchored the exhibition to Shenzhen, which has made a name for itself as China’s tech-industry headquarters in just a few decades. Projected onto a wall, Wind of Shenzhen (2019) portrays three-dimensional, aquamarine moving graphics that appear to be in endless transformation. A so-called “data painting,” Anadol’s work collects wind data from Shenzhen’s airport and uses custom algorithms to visualize the information as swirling formations. In Shenzhen, a city racing toward the future, it was fitting to reflect upon the new perspectives technology provides on our surroundings.

The phrase “humanizing technology” reminded me of modern philosopher Marshall McLuhan’s prescient theory of technology as “the extension of man”—the lens and structure through which we perceive and understand the world. Now, as advanced technologies become more closely tied to our lives than ever before, it is crucial, as Design Society’s exhibition illustrated, to consider the deep connections between human and machine, and the ways in which they shape one another.

“40 Years of Humanizing Technology” is on view at Design Society, Shenzhen, until February 16, 2020.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.