-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of AI WEIWEI’s “Ai Weiwei: Life Cycle” at the Marciano Art Foundation, Los Angeles, 2018–19. Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy the artist and Marciano Art Foundation.

Ai Weiwei has installed an epic ode to modern humanity across three galleries in Los Angeles—The Marciano Art Foundation (MAF), Jeffrey Deitch Gallery, and UTA Artist Space (designed by Ai himself)—with the unifying central theme being the ongoing global refugee crisis, situated within broader discussions on individuality, political repression, and the dangerous rejection of reality in favor of the fake.

Our journey through Ai’s exhibitions begins at the MAF’s old Masonic theater, where one is immediately struck by the harmonious beauty of a titanic installation. In place of the audience seats is a large rectangular bed of porcelain Sunflower Seeds (2010), referencing Mao’s claim that he was the sun shining down on the masses that turned towards him like sunflowers. Here, the seeds appear the same, but are actually hand-painted and unique, indicating the inherent value of all individuals, even if forced into the mass conformity of drab gray Mao suits or the issued jumpsuits of refugees. Similarly arranged in a neat rectangle like Seeds, on a section of floor closer to the orchestra pit, were fractured teapot Spouts (2015). These pale ceramic fragments recall bones in a mass grave, perhaps symbolizing the broken dreams of those who had hoped for a better future in their homelands, or the silenced voices of the persecuted.

The main attraction, presented on the stage, was Life Cycle (2018), a monumental life raft with 110 passengers, ghostly husks of young and old figures, fashioned from bamboo using a traditional Chinese kite-making technique. Ai’s use of bamboo—a much lighter material than the black rubber used in his other giant life raft, Law of the Journey (2017)—lends an ethereal feel to Life Cycle, while also acting as a metaphor for the resilience of refugees. A Chinese symbol of virtue, bamboo stands straight as honor, while its hollowness connotes modesty. Squeezed between the refugees and human traffickers are figures with human bodies and the heads of Chinese zodiac animals, a tongue-in-cheek suggestion that a displaced person will always be connected to his or her particular zodiac animal. The figures further add a sardonic subtext to the Chinese government’s calls for the repatriation of the Beijing Old Summer Palace zodiac head sculptures, plundered more than 150 years ago by British and French troops. Ai was forced into exile by the same government, which seems to care more about safeguarding cultural treasures that are sculptures, than cultural treasures that are human.

Adding to the fantastical, surreal quality of the installation are winged creatures, also of bamboo, suspended in mid-flight overhead. These phantasmagoric kites are inspired by the ancient Chinese compilation of mythologies, Classic of Mountains and Seas. Mixed into the historical fray are modern references to the father of the readymade, Marcel Duchamp; Vladimir Tatlin’s Tower, the unrealized monument to a communist utopia; and quotes from writers including Franz Kafka. By interweaving ancient and modern, local and global, Ai transforms the fight for human rights in China into a multicultural aesthetic language that offers us new perspectives on history as well as the current refugee crisis—an illuminating and multifaceted alternative to the one-sided narratives peddled by mainstream news media.

The Jeffrey Deitch Gallery was also transformed into another grand-scale visual happening. Here, Ai set up a sea of 5,929 handmade, wooden, Ming and Qing-Dynasty Stools (2013), the drab brown rows occasionally punctuated by a blue, yellow, green or red-painted stool. Lined up equidistantly with pinpoint accuracy such that an optical flow is achieved, the stools resemble rows of refugees waiting to be processed like numbers rather than humans. Though standing apart, the stools evoke a sense of common connection—beneath the worn circular seat, one can see the ancient Chinese mortise and tenon technique that joins together wooden pieces without nails. Employing this same technique, Ai takes the stationary stool and liberates it into his freewheeling abstraction Grapes (2017), a crescent-shaped structure of joined antique stools. Both works preserve and reshape these historical objects (which were lucky to have survived the Cultural Revolution, when most antiques were destroyed), perhaps alluding to the ways that current governments refashion the past to serve present political needs.

Ai complements the organic wood of the handmade stools with a seemingly antithetical material: plastic Lego bricks, a medium he discovered while watching his son play. Hanging on two opposite walls were Lego wall sculptures of animal heads from “Zodiac” (2018), superimposed on backgrounds from Ai’s famous “Study of Perspective” photographic series (1995–2003), depicting Ai giving the middle finger to various monuments of power. In Lego Dragon Zodiac (2018) we see a small figure of Ai, standing nonchalantly in front of Tiananmen Square, hands in pockets, wearing a t-shirt with the word “Fuck” spelled across his protruding chest. One wonders if the expletive is directed at authoritarian power, those who steal cultural artifacts, or perhaps at those who manufacture Lego and restrict free use (the Lego company initially refused to fulfill Ai’s bulk order of Lego bricks, saying his work was too political, but backed down after widespread criticism.) Notably, the shape and texture of the Lego lends a pixelated appearance to the images, apropos of our digital era, in which the lines between what’s real and fake are increasingly blurred.

Installation view of AI WEIWEI’s “Cao/Humanity” at UTA Artist Space, Los Angeles, 2018. Courtesy UTA Artist Space.

In a more intimate setting, “Cao/Humanity,” shown at UTA Artist Space, took a blade of grass as its starting point (“cao” is Mandarin pinyin for 草, “grass”). In Cao (2014), clumps of grass rendered in white marble “grow” out of hexagonal tiles in a neat grid in front of the hollowed Iron Tree Trunk (2015), bathed in the natural light streaming in through the skylight. Grass has a long history of being trampled, cut, ripped out and paved over; nonetheless, it continues to grow in its non-discriminatory, democratic way, sprouting around the palaces of dictators as well as under the mud shacks of peasant farmers. But Ai introduces an ironic twist: the blades of grass also resemble the barbs on the walls of the Chinese prison where he was detained and, by extension, the barbed wire that refugees encounter on border fences blocking their long march to nowhere.

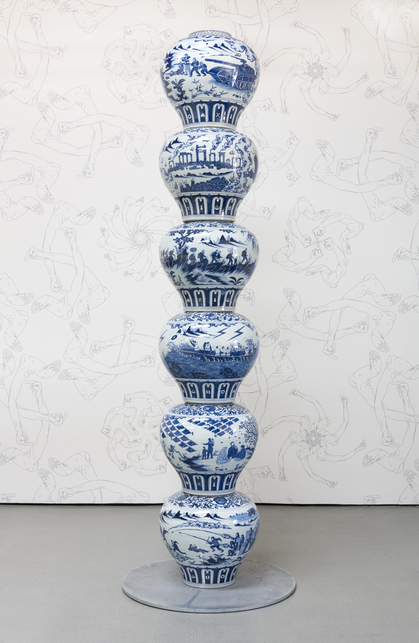

Like the works involving grass, stools and Lego, Ai’s Dragon Vase (2017) is also an exploration of fakeness with political overtones. At first glance, the piece appears to be a rose-colored Ming vase, but on closer inspection, one notices that the dragon portrayed on the object has six claws, parodying imperial dragons, which have only five. Moreover, one finds the incongruous Chinese term fake (发科) baked in the glaze. According to Ai, 发科, a Communist catchphrase, “sounds like ‘fuck’ but means ‘prosperous lesson’.” Appearing on the vase, Ai’s wordplay simultaneously authenticates its fakeness and insults the Chinese Communist Party. Ai takes aim at another treasure in Chinese culture with his jade-carved Handcuffs (2012)—while the material indicates luxury, the object ultimately symbolizes the limits placed on creative hands by the authoritarian Chinese government. Elsewhere, Stacked Vases as a Pillar (2017) resembles blue and white Ming vases placed on top of each other, but instead of idyllic Chinese court scenes, we see refugees fleeing bombed-out villages. In appropriating antique objects imbued with aesthetic value to comment on dire situations, from repression in China to the refugee crisis, Ai warns against embracing artifice that masks grim realities.

The sheer range of Ai’s materials and mediums was fascinating. Ai uses digital technology and visitors to the show in his 2018 installation Humanity. In a back room lined with gold wallpaper depicting CCTV cameras, the Twitter logo, and handcuffs, viewers are encouraged to read excerpts from his book on refugees, also titled Humanity. Each person’s reading is filmed and then uploaded to the artist’s Instagram, underscoring the reality that any one of us can be displaced and dispossessed at any moment.

From pottery artifacts, archeologists can piece together the histories of civilizations. Imagine archeologists inspecting fragments of Ai’s pottery, piecing together the story of our age, where the escape from reality through virtual spaces, ideologies, and superficial comforts seems worryingly commonplace. Hopefully, we won’t define ourselves by these artificial constructs, but—to paraphrase what the artist often says—by how we treat others. Perhaps no one in the future will believe how the planet could so callously ignore political crises, staying silent in the face of oppression or, worse, actively mistreating those who require help. We can only hope the course of this narrative changes, and archeologists will piece together a more dignified ending, earning us the right to use the word “humanity.” Otherwise, a different intonation of “cao” (肏) will be invoked and the show will be understood not as “Grass/Humanity” but as “Fuck/Humanity.”

*Ai’s blue Flag for Human Rights (2018)—depicting a Rohingya refugee girl’s footprint—flies outside UTA Artist Space at half-mast in honor of its founder, our dear mutual friend, Joshua Roth.

This cross-Los Angeles experience was envisioned by Josh, who died before he could see the project realized. Josh was an innovator who crossed the divide between talent agency and art gallery. He combined his lawyerly skills and aesthetic intuition with a warm, empathetic personality to bring Los Angeles Ai Weiwei’s epic to humanity. Indeed, Josh left his own footprint here in Los Angeles.

He will be missed by us all.

Andrew Cohen is ArtAsiaPacific’s Switzerland desk editor.

Ai Weiwei’s “Cao/Humanity” is on view at UTA Artist Space until December 15, 2018; “Zodiac” is on view at Jeffrey Deitch until January 5, 2019; and “Life Cycle” is on view at the Marciano Art Foundation until March 3, 2019, all in Los Angeles.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.