-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

An Artist is Trying to Return to ‘Being a Writer’

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook

For her first solo exhibition in her home country in almost seven years, veteran Thai artist Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook is writing a book. Writing has often played a significant role in her art—as seen on the occasions when she delivered art lectures to corpses, or with the prose-poetry that fills her catalogs—but, as she confessed in a recent interview, “maybe I have never gotten serious with it.” Accordingly, Araya is writing a novel during the almost seven-month run of her exhibition at Bangkok’s 100 Tonson Gallery, which includes multimedia works that act as witnesses to her writing process, or rather, her process of “trying to return to being a writer.”

The contents of the book remain a topic of conjecture, and by the same token, the gallery was practically empty for the first month of the show, save for a board with the exhibition title mounted on the wall, much to the bemusement of many Thai visitors who entered the space in June. Such conceptual pranksterism is characteristic of Araya, who revels in shocking the Thai art establishment, and who did not attend the show’s opening reception in July, but, rather, sent four body doubles to attend in her stead. This all went unexplained in the exhibition’s press release, but a hint as to the meaning of the stunt may be found in the artist’s statement in a recent interview: “In my return to writing this time, I am dancing in the midst of nostalgia with my unfamiliar self.”

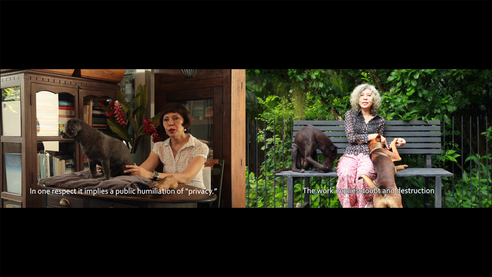

The themes of reminiscence and the estrangement of self are most evident in I Was Just Told That My Work is More or Less Too Sad for Christmas (2017). The video comprises footage from the artist’s most famous projects, such as performative works that see Thai monks discussing reproductions of western artworks with villagers, and documentation of her installation-performance for Documenta 13, where, over the course of three weeks, she lived in a house fitted with monitors showing her stray being fed and cared for in Thailand, on the exhibition site in Kassel. The video also features split-screen scenes in which two versions of Araya simultaneously muse about death and art; on one side of the frame, Araya impersonates a collector, petting a sedate mongrel, while on the other, she sits on a bench, her companion from Documenta sitting beside her as another dog plays restlessly at her feet. The footage of her past projects drips with nostalgia, but the invention of multiple personas renders the self subject to a distanced perspective, deliberately vulnerable to being re-written.

Continuing in this self-reflexive vein, many of the sculptures in the show read as the artist’s self-portraits. An installation in the corner that shares its title with the exhibition features two tiny statuettes of Araya with her unmistakable white hair: in one she frolics gayly in a beautiful swath of fabric, while in the other she hangs upside down from her feet, naked and abject. In The Dead Ovary Lullaby (2016), a life-size woman reclines inside an aluminum clam-shell-like structure, her head resting next to the blank pages of a book while a dog lies curled at her feet. Her facial features are uniformly white and undefined, suggestive of the unresolved state of the artist/writer’s identity.

Moving images and canines populate other parts of the gallery. Some Unexpected Events Sometimes Bring Momentary Happiness (2017), comprises a sculptural rendering of a woman’s thighs and an eerily detached hand, reaching down from nowhere to touch a dog’s head. Grainy video footage of the same scene is projected onto the sculptures and floor, replicating a dog’s eye view and illustrating the ease with which this contemporary master moves between media. Of course, the sculptures and the videos are just part of this equation; the book that parallels these works is still forthcoming, and until its publication the exhibition will inevitably remain incomplete, poignantly suspended in a permanent state of “trying to return.”

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s “An Artist is Trying to Return to ‘Being a Writer’” is on view at 100 Tonson Gallery, Bangkok, until January 14, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.