-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of ERIKA SCOTT’s The Revolving Doormat, 2021, trampoline, construction adhesive, fairy lights, computer keyboard keys, mirror, aquarium helicopter ornament, flashlight, water cooler, knife holder, cat sculpture, arachnid specimen, amoeba wall decoration, hardwood ply stand with Queensland maple veneer, dimensions variable, at “On Fire: Climate and Crisis,” Institute of Modern Art (IMA), Brisbane, 2021. Photo by Carl Warner. Courtesy the artist.

For months during 2019 and 2020, smoke-filled skies turned Australian summer days gray, orange, sometimes black. Disaster, suddenly more immediate than impending, breached the frontier of daily life. Known as the Black Summer, it inspired “On Fire: Climate and Crisis,” an exhibition at Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art. Curated by Timothy Riley Walsh, the show presented new commissions and other works by 15 Queensland artists.

Partitioning the gallery and dominating the exhibition design were red floor-to-ceiling welder’s curtains—objects that protect and signal danger. These were necessary to safely view Michael Candy’s movement-activated sculpture, Azimuth (2021), a large conical cage made from sterilizing UV-C bulbs that crawled in a slow circle. The exhibition text linked the sanitizing lights to Covid-19, insinuating that humans’ destruction of natural habitats is an important factor in the spread of diseases from animals to humans. The past’s impact on the present was a consistent, prescient concern in the show.

The first room established another prevailing theme: the relationship between the environment and colonization. Warraba Weatherall’s To know and possess (2021) transposes information from catalogue cards in Australian museum collections onto bronze memorial plaques, revealing the perverse equivalence produced when human remains such as skulls are collected as objects, the same as an axe or a stone. The memorializing format of the plaques wrests violent, tragic histories from archival data. In the show’s broader context, Weatherall’s work indicates that the colonial impulses to categorize and preside over other cultures, peoples, and the natural world are linked.

Works in the second space framed fire as political and cultural. Relative/Absolute (Fire) (1991), an incisive painting by the late artist Gordon Bennet (1955–2014), made this clear via an image of fire above six words—with three written in European languages and three in Indigenous Australian languages—all meaning fire. The title emphasizes linguistic construction, reminding us that meaning is made culturally, in language, and might be made differently. This resonates with Dale Harding’s tender Moreton Bay Ash branch smoulders slowly (2020). Intimate footage—of a branch beset by quiet flames, embers, smoke, and ash—is repeated across two screens, with a short lag between the two signifying gaps in contemporary knowledge of fire’s cultural significance, particularly land management. Indigenous people have used the long-burning ash to transport fire, including for controlled burns, a practice that is steeped in a rich history of caring for the environment.

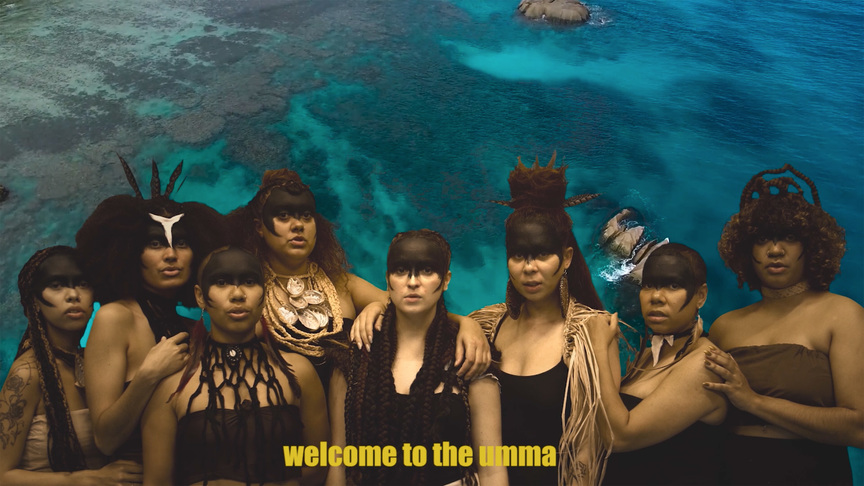

Including Candy’s work, the final space dealt with not-so-speculative futures. Circumventing an entirely bleak prognosis, Hannahs Brontë’s music video-like Umma’s Tongue–Molten at 6000° (2017) asserts resistance via a chorus of Black, Brown, and Indigenous women defiantly channelling the earth’s anger and resilience. Meanwhile, Erika Scott’s wonderfully, disturbingly excessive sculpture, The Revolving Doormat (2021), reads like an aftermath, redolent with domestic catastrophe. A large, round trampoline tipped sidewards is transformed into a repulsive melt: liquid nails cover the mesh in a thick impasto, household and childhood items fused to the surface while green fairy-lights glitter like broken glass.

Scott’s sculpture was one of two works that spoke most directly to that deadly season of fire. The other was Anne Wallace’s oil painting, Fire in the Hills (2019), depicting the oppressive domesticity of a formal lounge juxtaposed with a landscape in crisis, the blazing hills visible through carefully parted drapes. Wallace’s uncanny canvas renders a new, terrifying proximity between ecological disasters and the quotidian. However, other works were nuanced and came at the show’s central concerns at a slant. For example, Naomi Blacklock’s installation Lecanomancy (2021) comprised a cord of charred logs stacked carefully around a pool of shadowy, almost imperceptible water and a video of the artist playing an ocean harp to it. In the darkened gallery, the video’s soundwaves disturbed the water’s surface, making the near invisible visible. A clear impetus in the age of 24-hour news cycles, the work asks for sustained focus.

“On Fire: Climate and Crisis” rewarded return visits, its strength residing in its diverse, often concertedly political treatments of its themes. Given its full title viewers might have expected an exhibition of high drama, but much of the work required an invested viewer, and by extension, citizen.

“On Fire: Climate and Crisis” was on view at Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, from January 30 until March 20, 2021.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.