-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

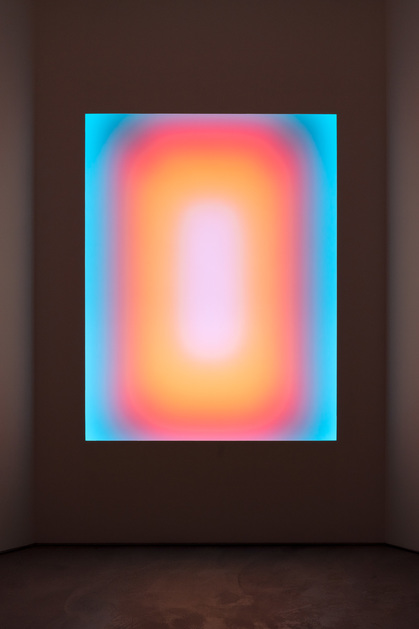

Installation view of JAMES TURRELL’s (left) Solon, Medium Rectangle Glass, 2019, LED light, etched glass and shallow space, 142.2 × 185.4 cm: 2 hr 30 min; and (right) Kakeroma, Small Glass, 2019, LED light, etched glass and shallow space, 48.3 × 68.6 cm: 2 hr 30 min, at “Bloom of Joy,” Pace Gallery, Hong Kong, 2020. All images courtesy Pace Gallery, London / Palo Alto / Seoul / Hong Kong / Geneva / New York.

Many artworks engage viewers in their object of representation: they are of a particular referent, a particular thing. But some art is to be valued for its perceptual experience, not for its object. It immerses us in the process of reflective perceiving. “Bloom of Joy” at Pace Gallery, Hong Kong, presented such an inquiry into human perception, inviting viewers into the beguiling world of Light and Space, the name of the West Coast artistic movement to which three of the four featured American artists belong.

Enclosed in a separate, darkened room was James Turrell’s Solon, Medium Rectangle Glass (2019), a hypnotizing LED light installation on etched glass where gradients of colors gently morph into different hues over a duration of two and a half hours. The manifold color fields—at times a mellow emerald on ultramarine, other times an ethereal blend of pink and purple—captivate viewers with their oneiric ambience. Inspired by his Quaker upbringing, Turrell employs no ostentatious symbolism in his work—it has “no object, no image and no focus […] You are looking at you looking.” This lack of a representational object draws attention back to the self, to our act of perceiving; light then “illuminates” the nature of aesthetic experience, guiding viewers to a reflexive contemplation. Light clarifies, awakening perceptions that we never paid attention to: as Maurice Merleau-Ponty postulated, we are normally aware of certain things against a background of a world of objects, but this would merely be one way of running our eyes over what is offered to us. Turrell demonstrates this by eliminating image altogether, leaving only a phenomenal field.

When Turrell’s art has no image, no object of focus, what is left of it? Light. This is precisely Turrell’s intent: to show viewers that light itself has a physicality, a thingness to it. In Kakeroma, Small Glass (2019), a smaller installation with metamorphosing colors similar to Solon, Turrell awards light its thingness by framing it in a small alcove, as if it were an artifact. This element effectively illustrates that thingness is accorded by context and of our perception thereof, that we are not merely receivers of percepts, but part of creating what we behold. Art is not dictated by the ontic thinghood of objects, but also formed by our consciousness.

Peter Alexander is another Light and Space artist, whose Butter Your Grits (Don’t That Just?) (2020) similarly calls attention to the wonders of light. It is bewildering how the assortment of colored urethane tubes seem from a distance to emanate light. As viewers get closer, they find this to be an illusion: the translucent material of the sculpture actually refracts the rays from the exhibition lighting overhead. We are led to question the apparent objectivity of our perception.

Mary Corse’s Untitled (Band) (2019) likewise toys with our perception. The set of five prints, featuring configurations of white, black, red, yellow, and blue bands embedded with glass microspheres, exemplifies a curious variant of op art—as the viewer moves, the refraction of light on the bands changes, in turn changing the paintings. Corse attempts to bring phenomenological reality into her practice: by utilizing refraction to bring light indirectly into her work, she recreates the mediation involved in human experience—personal and relative—rather than an unmediated objective reality, which is ultimately unattainable and therefore alien to us. Our perception then accords us our own version of reality—what really matters in our experience of the world.

As Merleau-Ponty theorized, consciousness is projective—we are the subjects which develop sensory data beyond their innate essence, creators of the world we behold. Turrell echoed this sentiment when he said of the perceivable world: “Who owns it? You who look. Not to be held, but known.” The works at Pace’s exhibition are an eloquent meditation not just on the properties of light but on the nature of our consciousness.

Emika Suzuki is an editorial intern at ArtAsiaPacific.

“Bloom of Joy” at Pace Gallery, Hong Kong, was on view from September 4 to October 15, 2020.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.