-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

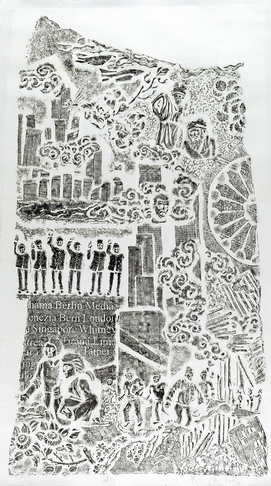

XU BING, Square Word Calligraphy by Khalil Gibran, 2008, ink on paper, 44 × 229 cm. Courtesy Ben Brown Fine Arts, Hong Kong.

“China–A Summer Show 2015,” currently on view at Ben Brown Fine Arts’s Hong Kong space, isn’t exactly an exhibition one might dub “new” or “exciting.” A group show with seemingly little connection between artists or artworks aside from regional heritage, its headliners—Ai Weiwei, Cai Guo-Qiang and Xu Bing—are all names that have become virtually synonymous with “contemporary Chinese art.” At first glance, what Ben Brown presents may seem rather clichéd and unoriginal, but upon closer inspection one realizes that something about it is quite different.

Hung on a dividing wall in front of the gallery’s entrance is Xu Bing’s Square Word Calligraphy by Khalil Gibran (2008). A horizontal ink-on-paper piece that depicts an excerpt from the 1912 novel Broken Wings by Lebanese-American poet Khalil Gibran (1883–1931), the work follows Xu’s original writing method, “Square Word Calligraphy,” which the artist devised 21 years ago. Throughout his career Xu has consistently stretched the limitations of text and language as visual forms, and has used the “Square Word Calligraphy” approach to explore the English language. In the series, what seem like Chinese characters are, in fact, English words that have been shaped to appear that way through dexterous transformations and positioning, creating little puzzles for both readers of Chinese and English. The two-meter-wide calligraphic work is supplemented with an English transcript that helps viewers decipher Xu’s script, which in turn makes the seemingly cryptic work very approachable.

Sharing the gallery are other works that center on Chinese culture. On one wall is Koon Wai Bong’s composite of paintings, which together make a tall group of bamboos evocative of those by literati painter Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322). Meanwhile, in the center of the room sits six of Ai Weiwei’s 1001 Qing dynasty chairs, which faces Cai Guo-Qiang’s “Non-Transparent” (2006) ink-rubbing series. “Non-Transparent” was derived from Cai’s 2006 exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, which featured a monumental piece of limestone carved with various scenes from modern history. Using the limestone sculpture as a base for the ink-rubbing series, Cai created a mesmerizing visual timeline, illustrating key moments from the early 2000s. Non-Trasnparent No.5 focuses on the gay rights movement, with images of same-sex couples surrounded by flowers and birds, while the prints of fireworks and ecstactic people in No.1 shows the Beijing Olympics bid-winning celebrations of 2001. The prints, while visually softer than its source sculputre, is just as captivating.

Turning into the far-right section of the gallery, visitors are introduced to Guo Hongwei, whose work occupies over half of the space. Five paintings from three different sets of work by the young Sichuan artist share an overarching theme of memory, with both oil paint and watercolor carefully manipulated to induce introspection in the viewers. At a normal viewing distance, two ochre monotone pieces from the series “The Temporary Existence” (all works 2011) appear minimal. The Temporary Existence 5 portrays a mundane interior scene, featuring a wall framed with a curtain section on one side and an electrical socket and wall lamp on the other. Narrowing the perspective, The Temporary Existence 8 is a detailed depiction of a set of purple curtains highlighted in parts by the daylight that they are attempting to shield. Exploiting the use of color and light, Guo instantly draws the viewer into the entirety of his works by playing with various vantage points. Despite being vastly different from its adjacent work—Zhang Huan’s Memory Door (Gun)(2007), a piece of wonderfully detailed labor featuring silkscreens mounted on an antique door adorned with bas-relief woodcarvings—Guo’s paintings are presented as a fitting counterpart to the contemporary masters exhibited in the show.

On the opposite side of the gallery is a gray-walled room dedicated exclusively to the work of Chen Wei, a 35-year-old musician-turned-photographer based in Beijing. The focus on this emerging artist comes as no surprise, since Chen has been continuously exhibiting both locally and abroad since his debut solo show at Beijing’s Platform China in 2008. His work is also currently a part of “China 8,” a monumental multi-venue survey of Chinese contemporary art in Germany. The reason for his popularity is evident: reminiscent of Jeff Wall’s cinematographic photographs, Chen’s compositions are carefully arranged, leaving the narrative of each image open-ended for viewers to expand on their own. For example, In the Waves #1 (2013) captures a curious moment inside a nightclub, where colorful lights spotlight a group of people dancing; yet the scene appears lifeless, as the figures appear to be frozen in time. Chen sheds light on the darkness of places that bring about so-called happiness and, as a result, reveals the sense of disillusionment and desire for escapism that permeates modern society.

While “China–A Summer Show” lacks the thrill of the new, its revisiting of time-honored works, as well as its display of young artists who show promise, leaves the viewer inspired by the exhibition. So whether it be to catch up on familiar contemporary works, or to discover new pieces, the show is well worth the visit.

“China–A Summer Show 2015” is on view at Ben Brown Fine Arts until September 10, 2015.