-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

The participants of the 79-day Umbrella Movement in 2014 had but one, simple—even romantic—goal: to achieve democracy for Hong Kong. While this was ultimately unsuccessful, leaving many bitter and jaded about the city’s political future, the protests also fathered a long list of unintended consequences: the mainstream rise of localism, the return of Hong Kong’s presence in international papers, countless documentaries and films, as well as an impressive array of public art with its own dedicated Wikipedia page.

Joining the movement’s list of peripheral outcomes three years later is the shift in Pak Sheung Chuen’s art. Para Site’s catalog describes the artist’s recent show as embodying Pak’s experience of trauma and process of self-healing, but the most prevalent sentiment looming over the space was that of obsession—one that was at times hauntingly beautiful and at others spine-chilling.

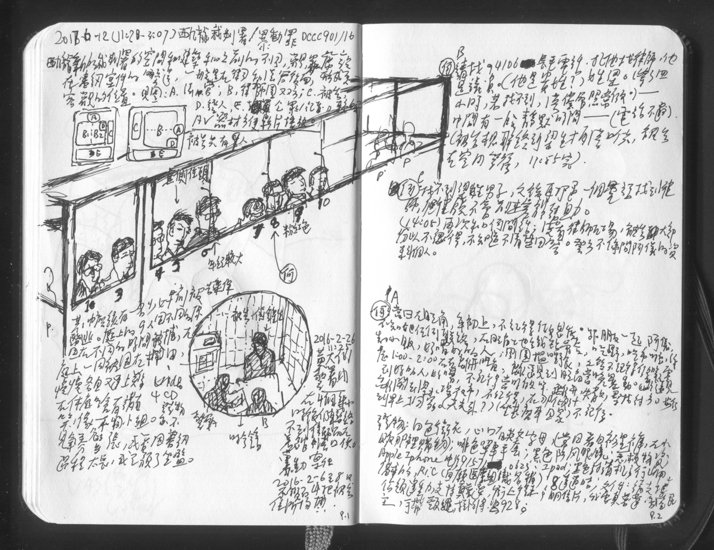

Perhaps Pak is aware of this himself, having named one of the series featured in the exhibition “Nightmare Wallpaper” (2017). These earthy, abstract-patterned wood panels were the first to greet viewers at the entrance. They are the product of sketches that Pak produced when he attended court hearings of political cases with the fervor of a dedicated churchgoer. At the show, the raw drawings—inscribed in the artist’s notebooks alongside squished, illegible writing—were also collected and presented. In “The Seal” (2017), the artist’s scrawls were transformed into black, life-sized abstract figures that jump out at viewers from the clinical white walls, demanding attention and understanding. Another group of artwork concerns what Pak calls “artefacts.” One such memento is a set of three harmless-looking spoons, which Pak collected when he shared meals with a defendant charged with rioting at the “Mong Kok Incident” in February 2016. The defendant noticed that Pak was taking the spoons with him but “it didn’t seem [to] bother him…Spoons in Christianity are a liturgical implement, a medium for sharing the pain of Christ in the Holy Sacrifice,” Pak explained in a printed note next to the items.

Installation view of “Chris Evans, Pak Sheung Chuen: Two Exhibitions” at Para Site, Hong Kong, 2017. Courtesy the artists and Para Site.

Some pieces are less abstract. Photographs from a performance art series about the ease of closing in on a target show Pak stealthily going up to political figures such as Joshua Wong—the Occupy protests’ bespectacled poster boy—and kidnapped bookseller Lam Wing-kee during demonstrations in June, 2016 and July, 2017, respectively. In Liaison Office of CPG Incident (2017) and Mong Kok Incident (2017), two televisions on the floor played scenes of Mong Kok and Sai Ying Pun in daytime, deceptively calm and quiet. Whatever visible scars the heated clashes between protesters and police had left in the two locations were forcefully erased—but with a single brick encased in a glossy glass dome next to one of the televisions, Pak refuses to let visitors forget the desperation that went down on the streets of Mong Kok.

The artworks and sketches—each retelling a specific court case or political incident—were accompanied by lengthy text explanations that served as invaluable background for those who are not from the city. For those who have called Hong Kong home or have no other place to call home, the texts were heart-wrenching stories of those who have fallen victim to the system, including Howard Lam—who mysteriously turned up one morning in August this year with cross-shaped staples on his leg, claiming to be the victim of mainland agents—and young localist Lee Sin-yi, who allegedly fled to Taiwan after being charged with rioting. In a way, Pak is not unlike the young social activists that he portrays: if they could not keep the politics out of their heads or lives, they might as well throw their lives into the political—the only difference being that the activists’ mediums were protests and Pak’s is art.

Taking up the other end of the room was Chris Evans’ exhibition, which—despite being similarly billed as an exploration of the relationship between the public and private domains—dimmed in comparison in its narrative and theme, especially since there were few explanations in the show or the catalog to justify the presence of the soft pastel paintings and sculptural “cowlicks” in the space. Or perhaps, as a Hongkonger myself, it was difficult for me to isolate my verdict of art from the politics that penetrates every aspect of our lives. By crystallizing the state of politics in his artwork, Pak became reborn—and so have the viewers who have been touched by his work.

Installation view of “Chris Evans, Pak Sheung Chuen: Two Exhibitions” at Para Site, Hong Kong, 2017. Courtesy the artists and Para Site.

“Chris Evans, Pak Sheung Chuen: Two Exhibitions” is on view at Para Site, Hong Kong, until December 3, 2017.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.