-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

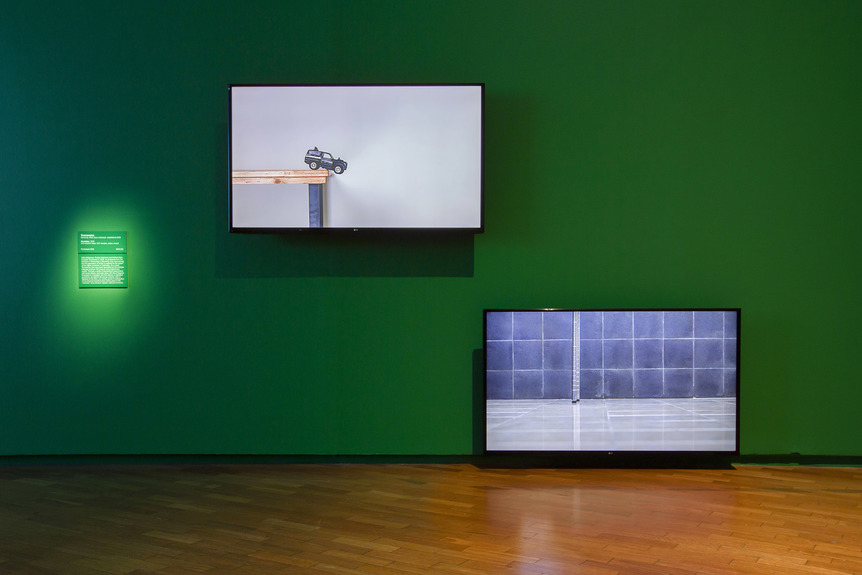

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of TISNA SANJAYA’s Seni penjernih dialog (Art as purifying dialogue), 2019, carved wooden boat, metal structure and horn speakers, spoken word performance, single-channel video, dimensions variable, at “Contemporary Worlds: Indonesia,” National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2019. Courtesy the artist.

In her essay “Suddenly, We Arrived . . . Polarities and Paradoxes of Indonesian Contemporary Art,” Leonor Veiga identified syncretism, the “layering of one culture atop the other, without either being erased,” as “one of the country’s strongest elements.” Considering Indonesia’s complex history and ethnic diversity, how does one go about staging a unified major survey of contemporary Indonesian art? The National Gallery of Australia took on this challenge with “Contemporary Worlds: Indonesia,” focusing on works by 24 Indonesian artists created during the Reformasi period, after the end of President Suharto’s repressive regime in 1998. Spanning a variety of media including painting, installation, sculpture, and performance, the exhibition reflected on Indonesia’s post-colonial identity, tradition, and globalization.

The ambitious exhibition acknowledged this syncretism through works such as Zico Albaiquni’s The stage of earthly delight I, II and III (2018), which consider historical and ideological influences on the development of Indonesian art. The palm trees in the backgrounds reference idyllic Mooi Indie landscapes, yet the 19th century Dutch genre is subverted by the harsh, fluorescent color scheme, exposing the fallacies of these romanticized colonial constructions. In earthly delight III (2018), Albaiquni alludes to a more recent chapter of art history with a rendering of Jim Supangkat’s Ken Dedes (1975) sculpture in the composition’s middle ground. The sculpture had riled the Indonesian public due to its juxtaposition of a traditional Hindu bust of Queen Ken Dedes and a crude painting of a topless female in jeans with her zipper undone—the latter considered by detractors to be a sign of lax Western attitudes to sexuality that were at odds with Indonesian mores. Albaiquni’s series of paintings thus speculate on the tensions between tradition, locality, and foreign influence throughout Indonesian art history. Unfortunately, these works, with their many symbols and allusions, run the risk of losing their historical resonance before Australian audiences, due to the cursory wall text.

Jompet Kuswidananto’s Memanggungkan kebersamaan (Staging collectivism) (2013) is similarly grounded in localism. The installation comprises 15 head coverings and pairs of wooden hands suspended over the back of an open truck. Microphones and loudspeakers lie despondently on the truck’s floor, seemingly abandoned mid-protest. The motorized hands clap slowly, an eerie mockery of the celebratory outburst on the streets of Indonesia following the end of Suharto’s regime, warning of complacency in the face of ostensibly democratic reforms, and calling for vigilance on the part of Indonesian citizens.

Some works benefited from the exhibition’s Australian context, notably Tita Salina’s installation 1001st Island – the most sustainable island in the archipelago (2015), a mass of plastic waste taken out of Jakarta Bay. In itself, the work ostensibly points to Indonesia’s environmental crisis, yet, staged in Australia, its commentary extends to the latter’s exploitation of the former by using it as a waste dump—last year alone, Australia imported 52 million kg of waste to East Java.

Considering, then, the complex relationship between the two countries, the lack of Indonesian-Australian artists such as Jumaadi, Dadang Christanto, Arahmaiani, and Woven Kolektif represented a missed opportunity. These diaspora artists are part of the syncretism that informs the exhibition, and their works reflect both the exodus caused by political and economic struggles outlined in the exhibition, as well as their engagement with their hyphenated identity.

The exhibition’s strength lay in the inclusion of younger artists who deliberately transcend the historical and national boundaries implied in the label “Indonesian.” The Tromarama collective, for instance, humorously investigate the more general idea of the conflation of virtual and physical worlds. Their video installation Quandary (2016) shows anthropomorphized objects split between two screens, with plastic bottles and balls moving across as if controlled by some invisible force. In Intercourse (2015), napkins and pages projected onto the back wall of the space are seemingly blown away by an electric fan displayed on a small screen facing this projection. This surreal set-up readily elicited laughter and astonishment from several visitors, a playful contrast to the sombre tone of preceding sections that had a more political bent. It was in these moments of brief surprise that the exhibition digressed from the trite and hackneyed formula of a blockbuster survey.

“Contemporary Worlds: Indonesia” is on view at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, until October 27, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.