-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Screenshot of MARAT DILMAN’s Untitled, 2018, object, in “Cybernomadism,” iata-art.org. Image by Peter Chung for ArtAsiaPacific.

“Cybernomadism”: Re-envisioning Futurity in Central Asia

To describe our pandemic-stricken times as “strange” is to cast Covid-19 as a historical outlier. This narrative is the product of beleaguered governments’ efforts at gaslighting the public into accepting that the emergence and spread of the disease is not—as scientists have warned for years—a logical outcome of planetary destruction, the wildlife trade, lack of governmental transparency, and unprepared healthcare systems. Given the systemic failings that have exacerbated this crisis, now is precisely the time to imagine alternative futures, as eight artists convey in the digital show “Cybernomadism,” presented by the Central Asia-focused International Art Development Association.

Curated by artist Anvar Musrepov, the exhibition occupies an awkward contextual position: it was conceived during quarantine soul-searching on life after Covid-19, but all of the works were created pre-pandemic and rooted in a post-Soviet perspective, often focused on dismantling narratives of authoritarian utopias—a disconnect acknowledged in the curatorial statement. Yet, the ease with which certain works translated across contexts attests to their conceptual conciseness, legibility, and relevance. Opening the show, Marat Dilman’s security camera with an “evil eye” amulet covering the lens evokes the pernicious expansion of state surveillance. The work takes on greater urgency as ethical debates surrounding the issue are colored by fears of contagion; countries including China and Russia have already seized on quarantine enforcement as justification for extending their monitoring of civilians.

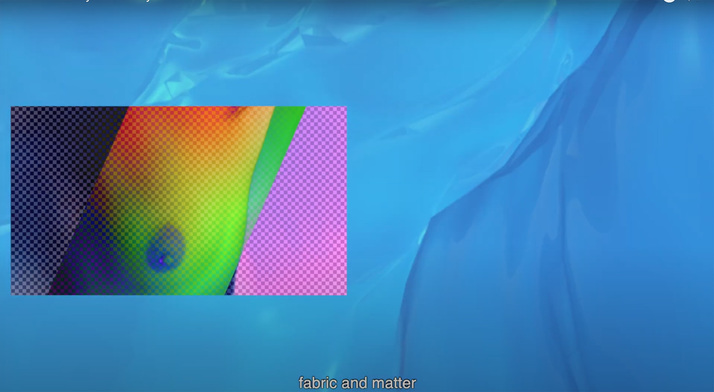

A standout is Nazira Karimi’s video What does my new body smell like (2018), which entrances and disturbs with its exploration of bodily disgust. Superimposing digitally rendered images of lapping waves and a naked female body, the work depicts the laborious process of editing the woman’s physique, from customizing the skin to scrubbing away body hair. The sparse subtitles resound with blunt and machinic simplicity: “fabric and matter / material and texture / zeros and ones.” It is intuitive to interpret Karimi’s work as a critique of the impossible beauty standards to which women are expected to conform, even, or especially, in the digital world. More essentially, the piece lays bare the oppressive underpinnings of ascribing normative value to biology. The leveraging of fear against an othered body, often on the falsified basis of uncleanliness and disease, has long been used to target minorities, and it is this xenophobic disgust that has resurged en force with Covid-19.

KRËLEX ZENTR, Transoxiana. A Tour for Newcomers, 2018, still from video: 17 min 41 sec. Courtesy the artists.

While most of the works raise questions about future conditions and aesthetics, Krëlex Zentr’s densely theoretical video Transoxiana. A Tour for Newcomers (2018) articulates a specific vision of a systemic overhaul spurred by government dysfunction. To a chaotic montage of appropriated news footage, photos of robotic contraptions, and clips from world-building video games, a digitally animated robot explains the emergence of a neotribalist Central Asian society that rejects nationalism and “repressive neoliberalism”—the latest ideologies foisted upon the region following the Soviet Union’s collapse—in favor of more sustainable and democratic governance facilitated by cybernetworks. Krëlex Zentr (Maria Vilkovisky and Ruthie Jenrbekova’s imaginary art institute) dissects the fallacy that Western capitalist modernity is the only viable model, highlighting the radical potential of a decolonial alternative.

There is much to unpack in “Cybernomadism,” and drawbacks in presentation, such as the distractingly disproportionate sizing of certain images and the absence of ancillary text on the works, detract from accessibility. While the forgoing of didactic captions facilitates freer interpretation, the elucidation of richly contextual projects might have been useful given the underrepresentation of Central Asia in global art history. For instance, the late Sergey Maslov’s multimedia series Baikonur 2 (1990–2002)—which employs digitally manipulated images of Kazakh people on the moon, among other extraterrestrial scenarios—may be illegible to audiences unfamiliar with Baikonur’s significance as a launch site for Soviet (and now Russian) space missions, or the broader themes of mythmaking, orientalism, and modernity in Maslov’s oeuvre. Nonetheless, “Cybernomadism” not only opens a window to the region’s contemporary art practices at a time when many borders are shut, but also illuminates the value of a Janus-faced futurism that looks forward while never losing sight of the past, with its myriad failures and near-misses.

Ophelia Lai is ArtAsiaPacific’s associate editor.

“Cybernomadism,” presented by the International Art Development Association, is available online.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.