-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Datumsoria: The Return of the Real

An electric buzzing sound fittingly accompanied the entrance to the show “Datumsoria: The Return of the Real” at the Centre for Art and Media in Karlsruhe this fall. Bringing together ten artists from Asia and Europe and curated by Chinese-American professor Zhang Ga, the exhibition aimed to investigate today’s digital realities and explore the emotive potential of cyberspace between factual and sensorial knowledge. Key figures of video art as well as younger new-media artists reflected on the role of robotic power as both passive contributor and active producer in artistic practices today.

Lured into the exhibition space by artist Laurent Grasso’s luminous LED screen Solar Wind (2017), which translates solar data, such as fluctuations in radiation emissions and magnetic fields, into flickering waves of color, viewers soon turned toward the source of mechanical humming behind them—Yan Lei’s Rêverie Reset (2016–17). The installation is a gigantic, cylindrical mechanical contraption of monitors that revolve around its central axis, each showing a variety of photographs—of weddings, animals, apartments and more—interspersed with screens displaying short descriptions on a colored background. The machine required viewers’ active participation: By scanning a QR-code, anyone could upload an image from their smartphones to the artist’s system. An algorithm analyzes the image as it is displayed on all monitors for a few seconds, before a textual account of its content is shown over a colored background generated to reflect the image’s average color shade. Finally, the collected data is added to the computer’s image pool, from which pictures are selected at random for display. Yan’s installation encourages viewers to choose and share visual memories that are accessible with the swipe of a finger—which will the public see, while others remain private? The artist’s machine blended myriad narratives, questioning our perception of the images that we encounter and the pictorial footprint we leave behind.

LIU XIAODONG, Weight of Insomnia, 2016, real-time streaming media, three robotic painting machines, canvas, 400 x 500 × 250 cm. Courtesy the artist and Chronus Art Centre, Shanghai.

On the opposite side of the space, Liu Xiaodong incorporated artificial perception of images into contemporary painting. His automated computer system Weight of Insomnia (2016) connected to three live cameras in Germany—one capturing the Brandenburg gate, one inside a BMW factory and the third located near a highway in Karlsruhe. Visitors bore witness as scenes from the live streams were continuously painted in monochrome on three canvases for the entire duration of the exhibition. Instead of clear shapes, Liu’s machine produced a vision of layered moments in time. The flow of visitors to the Berlin landmark are rendered as an undulating mass of crimson red brush strokes, and repetitive motions of the automobile factory’s machines blur in a cluster of bright orange.

Where Yan and Liu’s machines still bear some trace of human programming, artist Wang Yuyang takes the execution of automation to the next level. The artist created Wang Yuyang#, a software suite that conceives artworks on its own. Through an algorithmic search of social media and databases containing 3D models, various historic, literary and art historical references, as well as a collection of algorithms, Wang Yuyang# generates a sculptural or painterly project, which is then produced by the artist and thus given physical form. Suspended from the ceiling was Quarterly (2015), a curious sculpture of a metal object intersecting with the crown of a tree. The material disharmony of the installation and its apparent reference to a brutal, deadly event—a car crash, perhaps—incites the troubling notion of artificial intelligence overtaking human creativity, pronounced here in Wang Yuyang’s virtual doppelganger.

Carsten Nicolai’s mathematical Unitape (2015)—a projection showing a vertical flow of white patterns against a black background—made regular clicking sounds as white pixels passed through a virtual barrier on-screen, and emitted a crackling soundtrack for the space. Elsewhere, other installations provided a less explicit but more cerebral correlation to digital devices. Video art heavyweight Zhang Peili presented his Landscape with Spherical Architecture (2010), which consists of 36 small screens, each paired with an infrared motion sensor. The monitors are activated as visitors walk by, displaying a dynamic view of a desolate construction site that connected from screen to screen. Nearby, the installation Please Empty Your Pockets, Subsculpture 12 (2010) by Mexican artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer offered a humorous approach to the straining experience of airport security checks. Just as requested by the work’s title, visitors placed personal items on the installed conveyor belt moving through a scanning device, only to discover that, with the aid of hardware that shows augmented reality, additional, virtual objects were added to the collection as it reaches the other side.

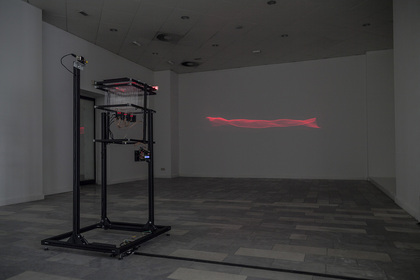

Moving past Ralf Baecker’s abstract laser landscape Mirage (2014) that visualizes Earth’s magnetic energy and George Legrady’s dreary Voice of Sisyphus (2011–17)—a constantly pixelated and de-pixelated study of a black-and-white photograph accompanied by a cacophonic soundscape—the exhibition concluded on a gaudy note in front of Nam June Paik’s psychedelic TV installation Internet Dream (1994). The artist’s idea of visual communication systems was conveyed via 52 screens showing a vibrant choreography of flickering, real-life images and graphic illustrations of people and objects. Just as visitors were guided into the show by chromatic impulses on a screen, Paik’s kaleidoscopic explosions sent viewers back off to reality where fall colors were in full swing, though not quite as lustrous as those rendered on a high-definition computer screen.

“Datumsoria: The Return of the Real” is on view at the Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe, until March 18, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.