-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

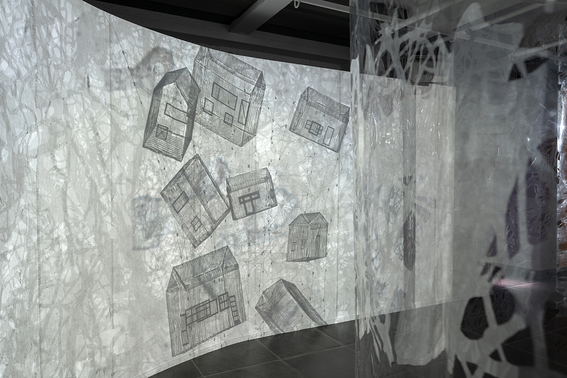

Installation view of ED PIEN’s solo exhibition at 1700 La Poste, Montreal, 2018–19. Photo by Guy L’Heureux. All images courtesy 1700 La Poste.

Toronto-based artist Ed Pien’s work centers on the human condition under the influences of trauma, violence and suffering. Deeply intrigued by what he found during his earlier investigation into the bodily impacts of the 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, his works frequently connect the human with the once-human, and blur the representational with the metaphorical. This is perhaps best illustrated in his visceral, disturbing Drawing on Hell (1997–98), which weaves together a composition of monstrous, contorted, humanoid figures. Pien’s fascination with the ghostly, ephemeral and illusory continues throughout his ouevre, as seen in his latest major solo exhibition at Montreal’s 1700 La Poste gallery, which presented large-scale drawing series and installations from the 1990s to the present.

Pien considers himself a mediator between materials, and often also incorporates different forces that are part of nature and everyday life, such as wind, light, breath and water. Installed above the entrance of the gallery was Psycho (2009), a work first displayed at The Tree Museum in Muskoka, composed of several two-way mirrors that move with the wind. Prefacing the exhibition, this work delves into and expands the sense of place between the seen and the unseen by way of the urban landscape, and its engagement with the human body in a subtle call-and-response.

The grouping of works in the exhibition activated the three-story gallery with a constant and organic flow of movements. The gallery’s basement was entirely taken over by an installation titled Revel (2011), comprised of a hand-cut mylar and plexiglass labyrinth hung from the ceiling, and a video projection featuring a young woman walking through a dingy space while assembling and relocating small mylar houses. The work is situated at a concurrence of changing lighting and wind situations by virtue of a projector and fans installed in different corners of the space. The movement of viewers adds another layer of complexity to the haunting atmosphere and its exploration of the sense of belonging in relation to migration, as it alters the physical presence of the work with a metaphysical effect that goes beyond a static materiality, as if the work could be breathing.

In recent years, Pien has spent time bringing awareness to the history of the Indigenous land on which Canada was brutally built. Through a series of mixed-media installations and works on fabrics, he takes the conversation surrounding land security and ownership back to one of the essential elements in the Canadian landscape: water. The work Sea Change (2017), for instance, a wall-sized cut-out piece that combines reflective film and Shoji paper to trace the silhouettes of sea creatures and humanoid figures, reflects on the unsafe water sources and resultant risk of disease that threaten Indigenous communities in Canada. Sea Change was originally presented at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, accompanied by text projecting a better future for water conservation, rendered in crystals by Merrell-Ann S. Phare, executive director of the Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources Inc., who regularly writes and speaks on water issues concerning Indigenous communities. Through the fictional underwater world depicted in Sea Change, where a variety of imagined and humanoid creatures co-exist, Pien acknowledges the privileges of colonial settlers and addresses how we are all complicit in erasing the existence of Indigenous peoples, a guilt that is bound to come back and haunt us if we treat it with silence.

While one may describe Pien’s work as otherworldly in some ways and culturally specific in others, it is perhaps more precise to view his work as a portal between the imaginary and the real, as attempts to break down the barrier between material reality and the intangible projections of fears and hopes. As Pien has experimented with bigger and more immersive scales in his practice, there has also been more mirroring of the present moment for us to think through who we are and how we are connected to this world that we live in. On the whole, the exhibition epitomized human experiences shaped by fear, loss and suffering, but also, more importantly, resilience, as reflected in the multiple states of being Pien proposes.

Ed Pien’s solo exhibition is on view at 1700 La Poste, Montreal, until January 20, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.