-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

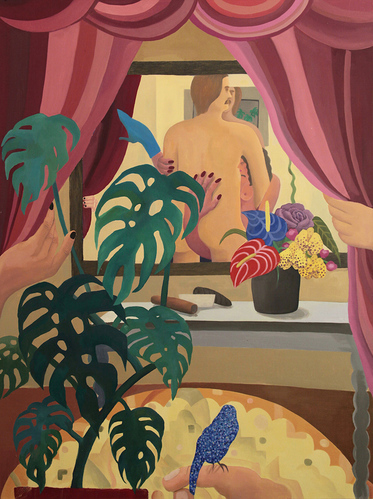

Installation view of GaHee Park’s “Every Day Was Yesterday,” at The Square Gallery, London, 2018. Courtesy Peter Mallett Photography, London.

Not since Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863)—a once sensationally controversial painting in which a woman identifiable as a prostitute stares defiantly from a scene composed after Titian’s coyly titillating Venus of Urbino (1583)—has art been a stranger to the subverted gaze. However, 17 years after Olympia caused outrage at the 1865 Paris salon, Manet played with the gaze in a different way. His A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) is remarkable for its deliberate lack of visual logic. As viewers, we see a barmaid starting directly out at us from the canvas, but it is the mirror behind her that engenders the painting’s strange effect. While the reflected image of the reveling crowd is flush with its mirror’s implied surface, to the right of the barmaid is the incongruously placed image of her back, and of a top-hatted man presumably ordering a drink from her, whose gaze we share while being forced also to look at a projection of ourselves.

The kind of ambiguous mise-en-scène that gives Manet’s canvas its power and subversive quality was prevalent among the paintings in GaHee Park’s “Every Day Was Yesterday,” mounted by Taymour Grahne at The Square Gallery, London. And, complementing the conspicuous voluptuousness in most of these works, it is this and other ambiguities that make them more sophisticated than simple but pleasing scenes of cartoonish erotica.

GAHEE PARK, Every Day Was Yesterday, 2017–18, oil on canvas, 177.8 × 139.7 cm. Courtesy the artist and Taymour Grahne, London.

The eponymous Every Day Was Yesterday (2017–18) is a prime example. The space around the canvas’s central intertwining bodies cannot rightly be described as background or foreground, as, in a cubistic touch, some of its segments appear deliberately confused. A dramatic vertical break in the center of the composition, uncannily bordered by a thin slice of a face in profile, makes one half of the room appear to stand before the other, subverting the viewer’s gaze and sense of location with regard to the picture’s subjects. In addition to this, the canvas is rife with voyeurs and diversions, directing and misdirecting the eye. A dog to the right of the image looks across it, perhaps at the two lovers or perhaps behind them, while another looks through a window directly at them. Even the lovers themselves are composed in a bewildering fashion. Their limbs contort in a way that is only just feasible, and a shadow cast by one of their faces obscures that of the other, prompting us to question the relation between this and the floating profile at the center of the piece. Along with a painting in the top right corner that seems to double and mirror the lovers themselves, this is an image that appears to work in twos. Duplicates of dogs, lovers, limbs and faces all serve to confound the boundaries between exhibitionism and voyeurism.

These same boundaries are questioned in the exhibition’s other pieces by the use of various frames, whether of windows, mirrors or paintings. In House Dance (2018), we are caught in the middle of a mise-en-abîme, viewing a couple having sex potentially from the perspective of one of the participants and, if not, then from a vantage point as defiant of logic as that in A Bar at the Folies-Bergère. In Smoking Room (2018), a cocktail-drinking couple, perhaps a woman and a man, perhaps both men, sit dressed and nonchalant in front of a picture in which a woman kneels, naked, in front of another cocktail-drinker.

Although each of these works engages with an unbalanced, or at least ambiguous, distribution of power as a function of the various acts of looking it involves, there is nonetheless a warmth and roundness to them reminiscent of, for example, Edward Burra’s The Snack Bar (1930). In their constant edging on the uncanny without descending fully into abstraction, they are more complex than Park’s earlier, more direct works, and therefore less immediately gratifying. With their colorful forms, off-kilter perspective and subtly sardonic humour, however, it doesn’t take long for these paintings to pay off.

GaHee Park’s “Every Day Was Yesterday” is on view at The Square Gallery, London, until June 13, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.