-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of LALA RUKH‘s Hieroglyphics (2008, left), VIDYA SAGAR’s Untitled (1992–93, center) and works from FRANCESCO CLEMENTE’s “Evening Raga” series (1992, right), at “Everything We Do is Music,” Drawing Room, London, 2017–18. Photo by Damian Griffiths. Courtesy Drawing Room.

Composer and artist John Cage famously insisted that “everything we do is music.” This principle was in fact appropriated from Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, an Indian philosopher who recognized the holistic, all encompassing and pan-accessible nature of artistic practices. Building on this adage and thought, the group show “Everything We Do is Music” delved into a foundational element of classical Indian music known as raga—melodic modes based on five to seven notes that offer a scale range within which a singer can improvise. Different ragas with their varying motifs and structures have historically been aligned with evoking myriad emotional responses, and for many, including curator Shanay Jhaveri, they are an integral part of family life in Mumbai. Visitors to the exhibition were visually introduced to the longstanding history of this tradition by three 17th to 18th century ragamalas—miniature paintings featuring musicians and dancers performing or that capture a specific melodic group’s character. From there, the show moved into modern and contemporary works, encompassing watercolor drawings, graphite works, animations and videos, providing insight into the multiple ways that Indian classical music has influenced and inspired visual artists.

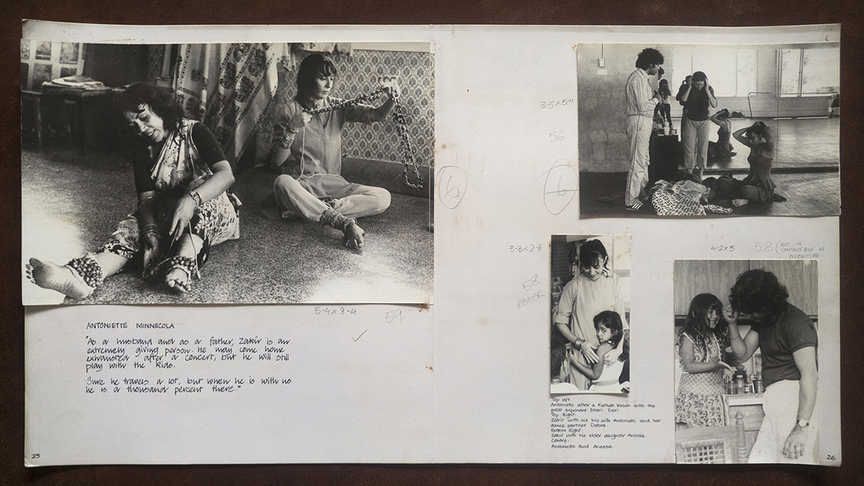

Presented in a room with works embodying diverse approaches to raga and with the soundtrack of Hetain Patel’s video Kanku Raga (2007) providing a steady aural backdrop, Dayanita Singh’s Pages from Zakir Hussain Maquette (1986) was immediately compelling. The work comprises an arrangement of book proofs from Singh’s first publication Zakir Hussain (1986), held in a glass case. Candid photos of Zakir Hussain, one of India’s foremost classical musicians, were interspersed on the pages with handwritten pencil annotations. The experimental composition of the book’s elements reflect Singh’s experience of travelling with raga musicians, which informed her editing process, enabling her to see her photographs akin to notes she could improvise with.

Close by, the intersection between music and visual forms was further consolidated in the repetitive markings of Nasreen Mohamedi and Prabhavathi Meppayil. Clustered in one edge of the main room, the works by the two artists emphasized the capacity for visual art to embody rhythm and to articulate subjective aural experiences. Mohamedi’s pieces, made while the artist listened to Hindustani classical music, captured a melodic essence. Untitled (c.1970), for example, resembles a framed piece of sheet music with a series of fractured staves falling into an abyss created by the central fold of the paper. This sense of a frenetic disorder resonated with Untitled (c.1970), where layers of black ink lines running from left to right appeared to create vibrations of different frequencies, only to be disrupted by a series of fainter marks that emerge from the center and meander down through the composition, ultimately landing at the bottom edge. Meppayil’s white, chalky canvases had a similar sense of movement achieved by repetitive and precise patterning. Twenty Five Seventeen (2017) presented rows of shallow indentations made with Indian goldsmith tools called thinnam. Twenty Six Seventeen (2017), on the other hand, was inlaid with strands of wire that seemed to propel themselves across the gesso panel, surfacing intermittently before fading again under the work’s facade.

A show of this scope and diversity with strong and enthusiastic curatorial execution can allow certain works to get lost. One such work was Matyas Wolter’s interpretation of a raga, made as a response to Michael Müller’s visceral graphite drawings, which was played through headphones hung on the inner wall of a small alcove. The positioning made the relationship between the works covert. Other groupings of works reinforced one another. Lala Rukh’s delicate Hieroglyphics (2008) was placed in a second gallery space with Vidya Sagar’s abstract geometric drawings and Francesco Clemente’s anthropomorphic series of watercolors, titled Evening Raga (1992). Rukh’s drawings, featuring silver forms floating at different heights of a horizontal expanse brought to mind soft chimes of varying pitches. The radical Pakistani artist’s work, seen in the UK for the first time, was a stunning example of how paintings can embody raga melodies while Clemente’s works, depicting human faces merged with animal parts, expressed a personal esoteric account.

Concluding the show was a standalone piece—Shahzia Sikander’s Disruption as Rapture (2016). Themes from the exhibition coalesced in the animation, which opened with the still image of a ragamala painting, overlaid with a musical score composed by musicians Du Yun and Ali Sethi. Slowly, the focal characters of the painting begin to levitate and are submerged by streams of flowers and a constellation of small rotating triangles. As the scenes change and the drawn figures transmorph into abstracted patterns and a tangle of snakes, and then re-emerge in a boat floating across a dark landscape to safety, the music moved too, incorporating choral chants. As with the overall show and its conceptual origins, the piece spoke of music’s ability to be emotionally resonant, dislocating, and very much an active part of life.

“Everything We Do is Music” is on view at the Drawing Room, London, until March 4, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.