-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

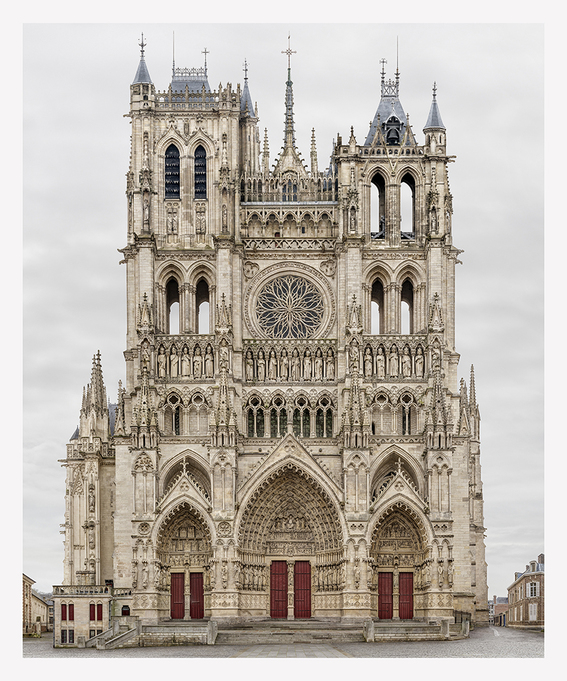

Installation view of MARKUS BRUNETTI’s “Facades” at Axel Vervoordt Gallery, Hong Kong, 2017. Courtesy Axel Vervoordt Gallery.

There was a heightened hush within the pristine premises of Axel Vervoordt Gallery’s Hong Kong space. Lining the walls of the exhibition “Facades” were seven of German artist Markus Brunetti’s hyper-realistic photographic prints of European medieval church and cathedral facades, each rendered in an uncompromising, straight-on perspective, standing at heights ranging from 1 to 1.6 meters. Inspired by their sacred subjects, the works initially emanate a guarded solemnity, but soon awaken a kind of voyeuristic wonderment: as the eye roves each canvas, a riveting wealth of detail unfolds, revealing intricate carvings, colonettes, saints, gargoyles and other minute architectural ornaments in unprecedented precision and textural clarity.

For over a decade, Brunetti and his partner Betty Schöner lived out of a truck as nomads, traveling through Germany, France, Italy and the rest of Europe to photograph churches and cathedrals of numerous periods and styles: Moorish, early Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque. Spending weeks—or in extreme cases, years—shooting each facade, Brunetti documents no more than a few square meters per exposure and then digitally reassembles the hundreds and thousands of high-definition frames into a coherent and monumental whole. The process is laborious and painstaking, involving Brunetti carefully manipulating each image—shot from street level—into one that portrays a central perspective as if shot from mid-air. Extraneous elements such as scaffolding and cables are then digitally erased, and the edited frames are meticulously stitched together in accordance with rigorous studies and calculations in proportion and scale.

Brunetti’s larger works—which can tower at up to two or three meters tall—did not make it into the exhibition in Hong Kong, which featured only his regular-sized editions. The series of facades, encased in plain white frames and hung closely together within the compact white cube space, become defined not so much by stature and grandiosity but a quiet, self-contained integrity stemming from Brunetti’s ongoing journey that has so far spanned over a decade. The serial, typological nature of his art is gently foregrounded, evoking dimensions of time, ritual, process and method.

Brunetti’s works recall and are themselves inspired by the iconic black-and-white documentary photographs by Bernd and Hilla Becher half a century ago, when they used formal, direct, centeredness to convey camera neutrality. Much like the Bechers’ water towers, steel mills and coal furnaces, which were photographed repeatedly and presented in a sequential, analytical manner, Brunetti’s facades are portrayed like specimens of a population, species or archive—singular yet ordinary. There is a clinical, self-effacing anonymity to the images, one that suspends photographic or creative authorship in two ways: its strict fidelity to objective structural reality and a frontal perspective that eschews human perception. In spite of—and because of—Brunetti’s arduous post-production interventions, the facades remain mysterious and remote, untainted by subjective expressionist or existential sensibility.

It is a carefully crafted neutrality that subverts the inherent didacticism of the photographic enterprise. Brunetti’s doing away of perspective “un-frames” the inevitable discriminatory framing exercise of the deceptively objective photographic act, and softens what Susan Sontag called the “aggression implicit in every use of the camera.” Modern photography’s aggression in particular lies in the photographer-auteur-dilettante’s desire to leave a mark, record his perspective, and imprint his own way of seeing into the world—all within an easy instant. In contrast, Brunetti’s painstaking yet dispassionate self-effacement constitutes a genuine homage to both his subject matter and the sanctity of the image—one that takes pleasure not in the technological medium but in the subject for its own sake, as well as in the patient construction and reconstruction of the image.

In an elegant coincidence, Brunetti’s laborious process echoes simultaneously that of the builders and craftsmen who laboured on the buildings centuries ago, as well as the cumbersome and time-consuming technical procedures at the dawn of photography itself. Taking the art form back to its roots, Brunetti’s facades humble the acts of looking, seeing and recording. By cleansing the image of perspective and subjectivity, his works allow the subject’s own pathos, accumulated over time, to shine through.

Markus Brunetti’s “Facades” is on view at Axel Vervoordt Gallery, Hong Kong, until August 26, 2017.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.