-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

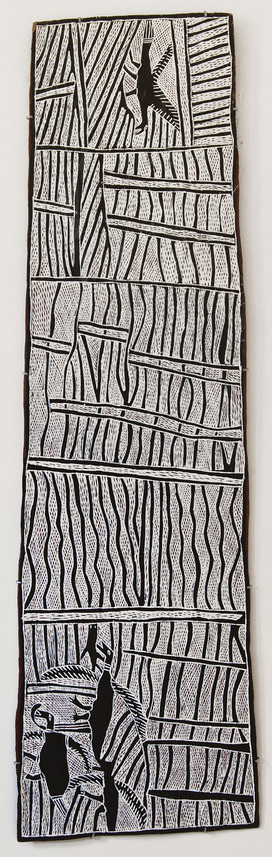

Installation view of NOŊGIRRŊA MARAWILI’s “From My Heart and Mind” at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2018–19. Courtesy the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

The works of Noŋgirrŋa Marawili (born circa 1939) are informed by the artist’s relationship to her ancestral country in northeast Arnhem Land and the Yolgnu lore that she grew up with. However, whereas many artists from this region favor traditional sacred designs, Marawili prefers secular forms, which allow her freedom for experimentation. The results of her unique process can be appreciated individually as beautiful, striking and balanced compositions, which nonetheless evoke her unbreakable connection to the land. In Marawili’s exhibition “From My Heart and Mind” at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, expertly curated by Cara Pinchbeck, viewers were privy to the chronology and major turning points of Marawili’s artistic development, anchored in robust formal inquiries—starting with her collaborations with her late husband Djutadjuta Mununggurr in the early 1990s, which feature gridded designs referencing fish traps and billabongs, followed by her forays into solo painting midway through the same decade.

A focused selection of bark paintings lined the gallery walls, elucidating a timeline. After beginning to create her own work, the first important shift in Marawili’s practice occurred in 2012. For complex cultural reasons, including rules within her clan on which designs and aspects of country can be painted by men and women respectively, Marawili moved from painting her husband’s inland Djapu country to depicting her community’s coastal lands of Madarrpa, exploring her experience of the cyclonic weather and dramatic currents. In a breathtakingly rapid evolution, the delineated segments of dense crosshatching in Frigate birds on the horizon (2012) appear to merge into a delicate freeform diamond net in Yathikpa (2013), and then a looser web of diamonds in the work of the same name, Yathikpa (2013)—diamonds being a design associated with flames in this context of the coastal sea of Yathikpa. In 2014’s Lightning and sea spray, the net disintegrates entirely in the centre of the painting, the gaping hole and delicate, dotted fronds emphasized and balanced compositionally by the strength of two red oblongs on the work’s top and bottom edges.

Though Marawili avoids clan designs and their associated sacrosanct stories, and adapts her practice to incorporate whatever materials are at hand (including painting in enamel on aluminum board when bark is unavailable, or using a broom as a brush), her images are not entirely devoid of traditional cultural significance. Like all good improvisations, they skillfully walk the line between convention and innovation, formally gesturing to what is expected but absent. This was evidenced in the exhibition’s final painting Baratjala – Lightning and the rock (2018), a rendering of delicate antennae emerging from ocher-toned dusty pink forms in natural and polymer pigments—an organic, ethereal composition seemingly aeons away from Frigate birds on the horizon, whose dense lines pay homage to the work of her forebears.

In the center of the room, a display of several prints by Marawili represented an important diversion from the paintings on the wall. When mechanical production was introduced to Yirrkala, elders decreed that “to paint the land you must use the land,” meaning that prints could not include sacred imagery as they could not be produced with natural materials. Works such as the 1998 screenprint Baru show that Marawili used this opportunity to experiment with her own irregular diamond motif, which later played a major role in her paintings.

Additionally, “From My Heart and Mind” included a group of larrakitj (memorial poles). Many of these depict Marawili’s ancestral home, but one 2013 larrakitj is festooned with teacups, the ubiquitous cuppas lined up as if marking time.

The neighboring gallery spaces featured Tony Tuckson’s sublime abstractions, placing Marawili’s show in conversation with the late painter’s retrospective. Tuckson was inspired by, among other things, the time he spent in Arnhem Land and his strong interest in collecting and curating Aboriginal art. While the influence of First Nations art and culture on Western artists like Tuckson have been acknowledged, less common are shows like “From My Heart and Mind,” which uncover the depth and breadth of individual Indigenous artists’ practices, furthering the understanding of their works. As her stunning paintings attest, Noŋgirrŋa Marawili is certainly an artist worthy of such attention.

Noŋgirrŋa Marawili’s “From My Heart and Mind” is on view at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, until February 24, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.