-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

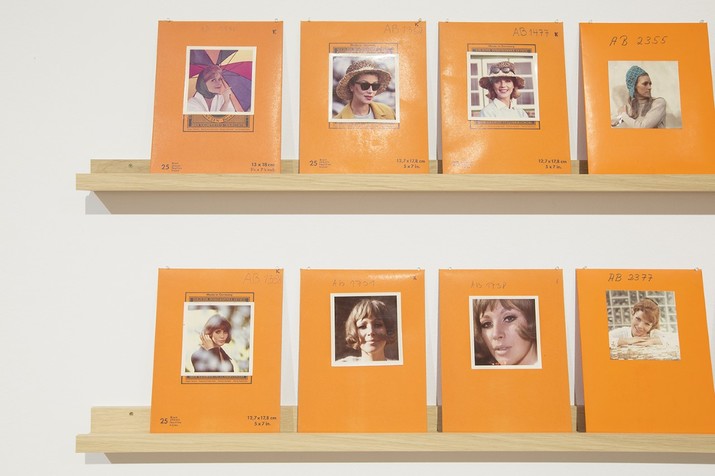

Installation view of FIONA TAN’s “GAAF” at Museum Ludwig, Cologne, 2019. Photo by Nina Siefke / Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln. Copyright the artist. Courtesy Museum Ludwig.

Hardship, privation, and displacement—post-war European society needed fantasy and frivolity and it found it, at least in Germany, in the many vibrant Agfacolor photographs that brightened the pages of countless magazines, advertisements, and brochures. Despite the film products’ past ubiquity, the Agfacolor archives—several thousand 6 × 6 color negatives and photographs taken between 1952 and 1968—have been consigned to storage on rudimentary metal racks in a windowless room within Cologne’s Museum Ludwig for the better part of 40 years. As part of the recent citywide “Artist Meets Archive” series initiated by the Internationale Photoszene Köln, Museum Ludwig invited artist and filmmaker Fiona Tan to realize an exhibition project with its photography collection as the starting point.

The result, “GAAF,” combines a selection of images from the Agfacolor archives with documentary photographs from Cologne’s post-war period, along with a focused selection of Tan’s own photography and videos.

Simultaneously a hiding place and a ruin of sorts, an archive is a bricolage of pictures, thoughts, and facts that marks the past as worthy

of preservation despite the enigma inherent in moments of stopped time. And it is this tension between seeing and reality, staging and authenticity, that confronts visitors as they encounter Tan’s reconstructed archive of boxes, binders, and folders juxtaposed with four horizontal rows of orange-bordered photographs displayed on an adjacent wall. Although the photographs themselves capture perfectly poised, colorfully attired, young and beautiful (white) women, there is a certain impersonal blandness to the subject matter and compositions. “What comes to mind is the word ‘gaaf’—colloquial Dutch for ‘neat’ or ‘perfect’,” Tan writes in the accompanying catalogue, before wondering, “What am I looking at? What is the photograph’s relevance today? And perhaps even more pertinently, what am I not seeing?”

One of the striking things about Tan’s assemblage of Agfacolor photographs is the extent

to which they speak to our present concerns despite their outdated aesthetics. Then, as

now, popular (and therefore pervasive) conceptions of female beauty tend toward the performative, a standardized simulacrum at odds with the complex realities of female identities. What are we not seeing underneath the shiny surfaces of today’s perfectly curated Instagram pictures that trade on irreality as much as the studied artificiality of the Agfacolor photographs, with their scores of carefree women on alpine or beach holidays?

In the adjoining gallery, Heinz Held’s black-and-white photographs of 1950s adolescents playing in Cologne’s war-ravaged streets or Ernst Haas’s compelling photographs of women returning home to post-war Vienna all stand in stark contrast to Agfa’s manufactured utopias. Here Tan follows the bewitching allure of affluence and leisure with the colorless realities of a Europe in ruins, the anguished faces of aging women or the blank expression of a young woman clutching a loaf of bread replacing aspirational and essentializing images with defiance and resilience. Tan has described herself as an “exhibition maker” and such curatorial gestures highlight her abiding interest in museum collections and archives.

Questions of identity, representation, and historicity continue to run through “GAAF,” particularly in Tan’s photographic display Vox Populi London (2012), which finds her negotiating contemporary urban identities in the British capital. Comprising loaned photos from Londoners’ family albums, the kaleidoscopic tapestry of private, authentic images again provides a striking counterpoint to the staged spontaneity of the Agfacolor advertisements. Snaps of weddings, holidays, family gatherings, and birthday parties, baby pictures, photos for their own sake—in Tan’s series, diversity becomes an end in itself, a celebratory invocation of individuality free from the commercializing agenda of mass-media images and the imperative to consume them.

In her concluding remarks in the catalogue, Tan engages with the issue of self-referential idealization once more: “The women portrayed in these Agfa photographs were never real to start with, but perhaps—even today—we somehow, very occasionally, still want them to be.” In today’s age of artificial intelligence assistants, often imbued with female voices, female names and stereotypically female attributes, perhaps the retrograde amnesia that pervades so much of the exhibition’s photographs is becoming a thing of the future. Just what kind of a story about contemporary life are we archiving for subsequent generations?

Fiona Tan’s “GAAF” is on view at Museum Ludwig, Cologne, until August 11, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.