-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Japan Society’s atrium was redesigned by HIROSHI SUGIMOTO, and now features his minimalist metal sculptures. Photo by Sugimoto Studio. Courtesy Sugimoto Studio and Japan Society, New York.

Before visitors set foot in Japan Society’s gallery to see Hiroshi Sugimoto’s “Gates of Paradise,” we are offered a glimpse of the Japanese photographer’s meticulously envisioned world: the lobby’s indoor greenery has been transformed into a rock garden, featuring bonsai trees and Sugimoto’s minimalist, metal sculptures. The recent renovations speak to his desire to create an all-encompassing experience not only through photography, but also via architecture, design and a study of global history.

In “Gates of Paradise,” Sugimoto journeys back to end of the 16th century and the height of what’s known as the “Christian Century” in Japan. The East-meets-West moment has been well documented, though it remains largely unknown in the United States. Along with the introduction of gunpowder brought to Japan by the Portuguese during the Age of Discovery, the Jesuits also imported their faith. The Japanese government responded by dispatching their own emissaries—four 13-year-old boys named Mancio Itō, Miguel Chijiwa, Julião Nakaura and Martinão Hara—known as the Tenshō Embassy. A map at the entrance of the gallery detailed the voyagers’ sea journey that eventually landed them in Lisbon two and a half years later. It is here that Sugimoto begins retracing their steps.

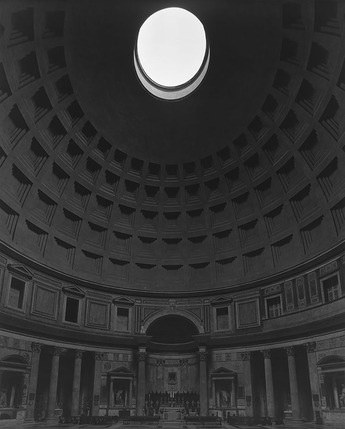

The photographic series opens with a black-and-white image, Mediterranean Sea, Cassis (1993). The horizon blurs into the sky, with no clear indication of where one ends and the other begins. We can imagine what it might have been like to encounter the body of water for the first time, and how it might emerge like a new world shrouded in mystery. Sugimoto’s photo of the Leaning Tower of Pisa (2014) deploys a similar method of obfuscation by keeping its subject out of focus, thereby spurring a feeling of timelessness. The emphasis on light rather than color, sense of place rather than people, can also be observed in his treatment of other sites visited by the Tenshō Embassy—Pantheon, Rome (2015), Pieta by Michelangelo (2016) in Florence, and Teatro Olimpico, Vicenza (2015). It was at the latter, in the old opera house, that the artist first came across a fresco memorializing “four Japanese-looking people.” This encounter with the famed quattro ragazzi ultimately sparked Sugimoto’s desire to see through their eyes.

Using his camera to travel back in time, Sugimoto’s personal narrative emerges through a retelling of the past. His photographs invoke unavoidable parallels between the New York-based artist’s life spent abroad and that of the Japanese individuals who ventured out into the world before him. Providing a biographical tangent to the exhibition, The Last Supper: Acts of God (1999–2012) revisits a piece unearthed from Sugimoto’s Chelsea storeroom, and which had suffered water damage as a result of flooding during Hurricane Sandy’s landfall in 2012. The curious, five-panel print originally captured the likeness of Leonardo da Vinci’s famous painting reproduced as life-size wax figures, which he photographed at a museum in Izu, Japan. After the images’ near destruction by a force beyond human control, the work has been reborn—visible stains and halo-like spots altering the piece’s meaning along with its physical appearance. Perhaps it’s not given a new life so much as it has a half-life, transformed into something ghostly, haunting.

Sugimoto’s photography goes beyond documentation to augment our experience of viewing art. Visiting the Baptistery of St. John in Florence, he photographed the bronze portal known as the Gates of Paradise, created by Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455) in the 15th century. By framing each relief, which highlights a different biblical scene from Adam and Eve through the age of Solomon, Sugimoto recasts those painstakingly crafted bronze panels as individual works of art in his series “Gates of Paradise” (2016). The viewer is offered a more detailed study of the portal than if they were to visit the actual site in Italy. For his diptych Red and White Plum Blossoms Under Moonlight (2014), Sugimoto photographed the Japanese masterpiece Red and White Plum Blossoms by Edo painter Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) by long exposure lit by lunar luminescence, with the resulting images mounted on screens to emulate the original. Sugimoto’s efforts yield something unexpected that echoes the source painting’s reverence for nature.

The nanban screens and artifacts—objects created in a style that was influenced by contact with European traders and missionaries—of which there are two rotations supplementing the exhibition, similarly examine the types of creative mimicry taking place during the period of international trade in the 16th and 17th centuries. There were instances of unintentional absurdity, as evident in Scenes of European Ways of Life (Momoyama period, 16th century), a Japanese attempt to paint in the Netherlandish style that resulted in oddly sized sheep and duplicate faces as if white European people all looked the same. Meanwhile, A Portuguese Trading Ship Arrives in Japan (Momoyama to Edo period, early 17th century) depicts Westerners rendered in traditional Japanese painting techniques. Unfortunately, by the time the Tenshō Embassy returned to Japan, the new leadership that had succeeded the previous daimyō (feudal lord) sought to expel Christianity and ordered the removal of Jesuit missionaries. For the next 250 years, Japan would remain completely isolated from the West. “Gates of Paradise” concluded by contemplating what is lost when open exchange gives way to building walls.

Mimi Wong is a New York desk editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

Hiroshi Sugimoto’s “Gates of Paradise” is on view at the Japan Society, New York, until January 7, 2018. It will travel to MOA Museum of Art, Atami, Japan, from October 5 to November 4, 2018; and the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum from November 23, 2018, until January 30, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.