-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

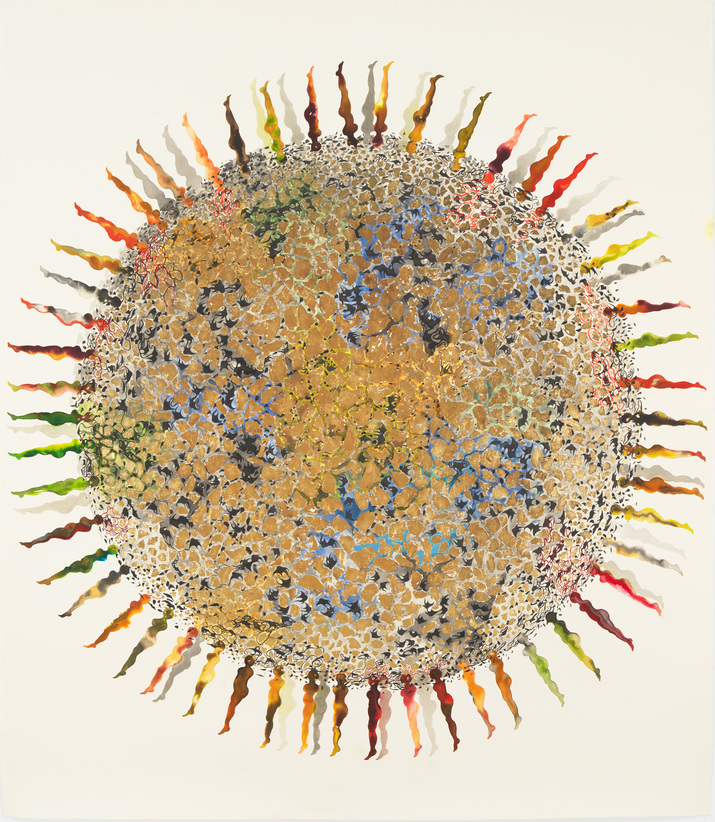

Installation view of SHAHZIA SIKANDER’s “Infinite Woman,” at Pilar Corrias, 2021. All images courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London.

“You’ll believe God is a woman,” or so pop sensation Ariana Grande’s song goes. Such seemed the edict of Pakistani-American multimedia artist Shahzia Sikander’s solo exhibition. In an incisive introduction to “Infinite Woman,” Black art historian Dorothy Price writes how Sikander posits a new kind of “world-forming” following an era of global destruction precipitated by colonialism and a Western neoliberalist agenda—one helmed by the female.

Sikander’s feminist world-forming strategy is one of playful (mis)recognition, unfolding in her cartographic reinventions which flanked the end of the gallery space. In the titular Infinite Woman (2021), gem-colored silhouettes of female figures radiate from a torched Earth-like sphere. But these are not women magnetized to or dependent on the Earth, they are women holding it together. Delicate, curling tendrils evocative of umbilical cords latch them onto the Earth’s surface, nurturing it. Sikander has the Earth suckling its mothers’ teats, as it has been doing across centuries of women’s unquestioned subservience to a patriarchal world-order, and their giving of unpaid domestic labor.

The face of a blue-skinned woman—or goddess—materializes out of sprawling watercolor washes across the surface of another remade Earth in Kindred (2021). This time, she is enveloped by strokes of black ink teeming with the energy of Sikander’s gestural application. Ink and color morph into undecipherable life forms that belong to this femme ecosystem. In traditional mappa mundi, medieval Christians looked to the East, where the sun rises, for imagery of the second coming of Christ. Embodied by these paintings, the second coming in Sikander’s typological system is that of the woman, filled with beauty and terrifying power.

Sikander’s intersectional approach to feminist and postcolonial politics comes through in her depictions of the oppressed “othered” subjects of the woman as well as the colonized. Trained as a miniaturist at the National College of Arts in Lahore, she developed her unique, contemporary approach to this time-honored Indo-Persian medium. European colonialism cut South Asian miniature manuscripts’ lives short, with many dismembered and sold for profit. Touchstone (2021), a mosaic encrusted in glass, depicts a female figure clutching a chalawa, a small, disappearing mythic farm animal, to her chest. Sikander blows-up the miniature to a monumental scale, such that instead of an exoticized totem, Touchstone, with its dominating presence and the fractured impression of its tiles, is an icon that subverts the miniature’s histories of dismemberment and reclaims its colonial (mis)treatment.

Beauty on its own—placid, gentle, and idyllic—can be boring. But in Flared (2020), the aesthetic beauty derived from sleek paint drips and flaring warm colors sours into something terrifying when one realizes this is a world set on fire. Whether it is in the process of renewal or self-destruction, one is not sure. In this apocalyptic wasteland, oil drums are torched and anthropomorphized, wherein their curved rims resemble human skeletons. Sikander stacks them into the vague shape of a Christmas tree, a common motif in her works since she discovered that oil rigs were called “Christmas trees” due to their conical shape, piped branches, and chain garlands in a 1962 British Petroleum magazine. Flared’s message on the colonialist origins of oil extraction is thus admittedly very on-the-nose, but this makes it no less true: global capitalism is built on the bones of the colonized.

Installation view of SHAHZIA SIKANDER’s Reckoning, 2020, digital video animation, sound, color: 4 min 14 sec, in collaboration with DU YUN, featuring ZEB BANGASH, with animation by PATRICK O’ROURKE, at “Infinite Woman,” at Pilar Corrias, 2021.

Reckoning (2020), a video in collaboration with Shanghai-born composer Du Yun, marked the endpoint of “Infinite Woman.” Here, one glimpses a shifting veil of poetic images: petals morph into warrior figures, into ambiguous archetypes of Empire and the oppressed before succumbing to darkness. Sunken into the gallery’s dimly-lit basement, the video room is a kind of ritual site, from which one literally emerges out of and up the stairs enlightened. But Reckoning, in its ambition to tackle the complex meatiness of colonialist and identity politics through vague, diverted metaphors, only leaves one unsatisfied.

Laying out a seductive slippage between fantasy and everyday politics, the utopian and dystopian, domination and subordination, “Infinite Woman” asks of the what-could-be’s: feminized world-formings and neo-colonialism gone too far. Just when the public thought it was safe to enter the gallery to escape the sordid reality of the mundane world, Sikander reminds us why the tales that hit the hardest are so often the ones that hit the closest to home.

Shahzia Sikander’s “Infinite Woman” was on view at Pilar Corrias, London, from October 12 to November 13, 2021.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.