-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

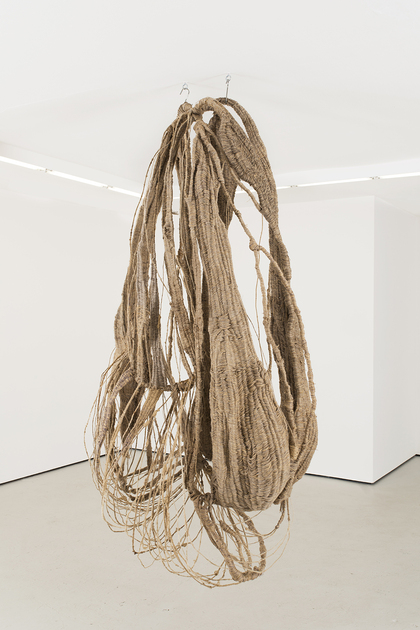

Installation view of SOOJIN KANG’s “Growth” at Unit9, London, 2017. Photo by this happened.xyz. Courtesy Unit9.

Three expansive, incomplete cocoons hung from the ceiling at London’s Unit9 Project Space. Tightly spun in parts and gaping in others, these bulbous hybrid forms discretely rotated, resembling bundles of brittle roots, redundant nests or shed skin. Hand-woven by the artist Soojin Kang, sections of raw linen, wild silk, jute, hemp, cotton and linen run into each other, forming the bodies of these handsome hollow shells. Frayed knots sprout from inside these panels, and spindly single strands grow outward and downward toward the floor.

These “pods” create a post-apocalyptic atmosphere. Installed equidistant from each other in the center of the gallery, Pod 1, 2 and 3 (all 2017) huddled together, offering support against an ambiguous threat. The unity between the forms reflects Kang’s practice. According to the artist, these works grew together and were made in tandem. Driven by intuition and a responsibility to the spools of fabrics she works with, Kang allowed the shades and gradation of the varied threads—all naturally dyed—to create patterns in the weave. En-masse, the mix of compressed and interlocking fibers created subtle patches of darkness and light. These inflections and the changes in tactility between the materials added to the subtle movement of the works. The wrapping motion created an orbit, directing viewers to ambulate and look in through the network of fibers.

Kang was pregnant and gave birth while making and installing these works. The impact of this on her practice was evident: the pieces have a womb-like quality and required gestation. The process of their formation was slow, with each small 20-cm square section taking at least a day. Following a technique learnt from banana leaf weavers during a recent residency in Calicut, India, Kang worked for three months on the pieces. The anxiety felt by the artist during this time was pronounced, for unlike her previous wall- and floor-based works, suspending the weighty dense weave caused sections to collapse. The unknown outcome made her insecure, she said. In recalling the memories of the process of creation, the artist described the unpredictable path that weaving took her down, calling the finished product an enjoyable accident.

These are not however completely without aesthetic precedent. The reference to Louise Bourgeois’s hanging sculptures, particularly Fée Couturière (1963), is evident, and Kang positions herself among a corpus of female artists who have questioned the ability to simultaneously be a mother and a successful artist. She challenges the thesis put forward most prominently by Marina Abramović that motherhood diminishes creative impulse. During our discussion, she repeatedly affirmed that the fulfillment of giving birth gave her strength to move forward: “It was so natural to do this while having a baby,” she explained. The repetitive weaving settled her and made her secure.

Kang respects her work and reiterates its agency, emphasizing that the pods come together of their own volition and develop personalities. The self-asserted distance between the artist and her creations gives the exhibition its edge. The three works appear conscious and in the process of organically repairing and regenerating themselves. The bound arches of wire form a framework, and the unfilled spaces between heavy sections of interlocking materials suggest that there is another cycle of growth to come. Although the artist was resolute in moving on from this scale, it is obvious that with another weaving residency in Nepal planned for this year, it will be a short hiatus.

Soojin Kang’s “Growth” is on view at Unit9 Project Space, London, until July 2, 2017.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.