-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

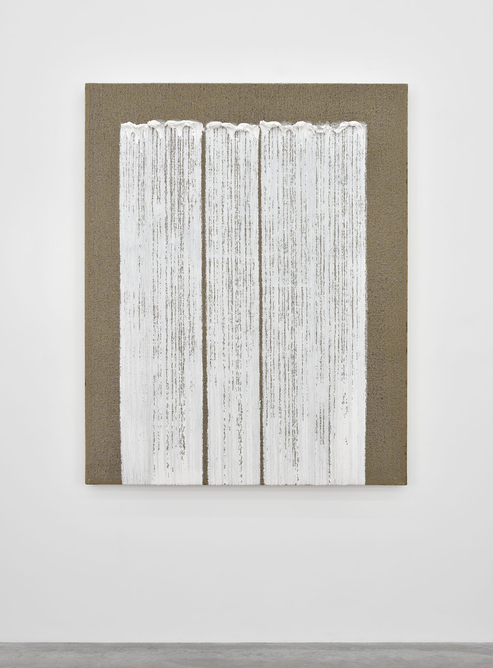

Installation view of HA CHONG-HYUN’s eponymous exhibition at Almine Rech Gallery, Paris, 2017. Courtesy the artist and Almine Rech Gallery.

Dansaekhwa, or “monochrome” painting, coalesced into an artistic movement in 1970s Korea, when President Park Chung-Hee expanded authoritarian power through martial law and ruled the Fourth Republic of South Korea under a dictatorship. Though artists such as Park Seo-Bo and Lee Ufan had begun painting monochromatic, abstract canvases in the 1960s, their creations contrasted with the politically charged performance art of Lee Kun-yong and Sung Neung-kyung, whose emphasis on the body and responses to the restrictions imposed by Park’s regime mobilized artists across social classes. Ha Chong-hyun belongs to the group of loosely affiliated Dansaekhwa practitioners, whose resurgence in the art market in the past several years has been met with great acclaim by collectors and gallerists—and surprise and gratitude by the artists. “I shouldn’t be here,” Ha Chong-hyun said, in a 2015 New Yorker article chronicling the rise of Dansaekhwa artists. “But to have this happen in my lifetime, I can’t be more thankful.”

At Almine Rech Gallery in Paris, 21 of the artist’s paintings, the majority of which were created in the past four years, demonstrated Ha’s ability to imbue paint with the qualities of sculpture. The artist uses a methodical, labor-intensive process to create energetic paintings on hemp cloth, recalling the sacks of aid supplies distributed to South Korea from the United States following the Second World War. Pushing the paint through the rough material’s dense weave results in layered, textural surfaces that are gradually built up to thick surfaces of white, cream and a captivating midnight blue-black. Many of the works are vividly gestural, such as Conjunction 15-164 (2015), whose short, thick strokes of white recall the minimalism of Robert Ryman, albeit in larger scale and with a framing that is more strictly defined. With their decidedly haphazard geometry, works such as Conjunction 15-147 (2015) and Conjunction 14-302 (B) (2014), in which jagged white lines streak across the frame, seem to be playful companions to the staid abstraction of Agnes Martin. That Ha’s work can draw such comparisons while maintaining their unique verve speaks to the appeal of Dansaekhwa artists in the contemporary global market, but also makes a case for Ha’s commitment to a studied, careful craft that he has developed over the past 40 years.

Since his move to abstract painting in the early 1970s, the artist has titled each of his works Conjunction, which are then serially titled alphanumerically. In the 2007 painting Conjunction 07-19 (A), long, even strokes of black oil paint are applied from the bottom of the cloth, terminating in thick impasto curls approximately four-fifths from the rough hemp’s top edge. Framing these black marks are a thin halo of oil that has separated from the pigment, staining the cloth and evoking the processual quality of Ha’s work. Conjunction 07-19 (B), from the same year, repeats this format but with white oil paint. Like many of the paintings in the gallery, it functions as a pendant piece, complementing the painting displayed beside it via color inversion. The 2015 work Conjunction 15-143 presents a dark blue-black surface with lighter areas of blue paint streaking up and folding over as in the 07-19 pair. Its companion is Conjunction 15-144, rendered in white paint on naked hemp. However, the surface of the painting is not purely white nor evenly smooth, and is pockmarked with tiny strains of tan burlap that peek through the glossy paint. These inconsistencies, far from detracting from the work, generate excitement in the viewer; looking up at the egg-and-dart moulding of the gallery space, similar patches of brown wood were visible among the peeling white paint. Perhaps this was a circumstantial effect, but it is evocative of the nature of Ha Chong-hyun’s paintings, where the true pleasure of seeing bubbles up from within and emanates outward. The artist has stated that his art taps into to his philosophy that painting and physicality should be in union—or conjunction. His exhibition proved that the pursuit of this unity is as vivifying for the viewer as it is for the artist.

Ha Chong-hyun’s eponymous exhibition is on view at Almine Rech Gallery, Paris, until June 3, 2017.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.