-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

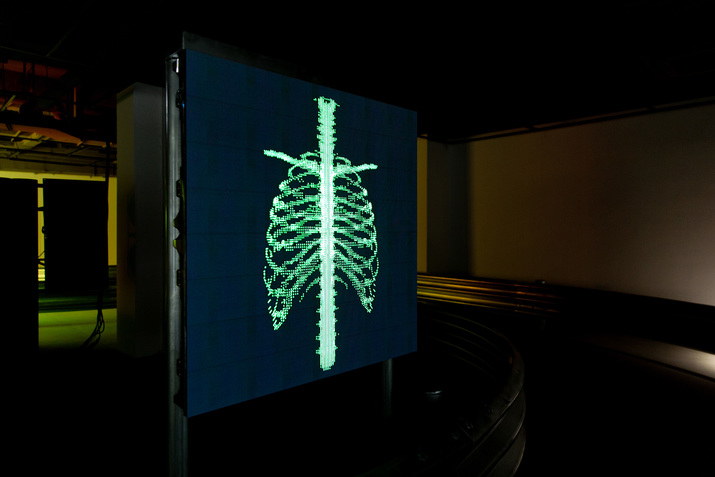

Installation view of ZHANG DING’s solo exhibition “High-Speed Forms,” at OCAT Shanghai, 2019–20. Courtesy the artist.

OCAT’s new Shanghai venue in Jing’an District, around the corner from its previous location, is comprised of interconnected subterranean areas punctuated by concrete columns. This underground car-park like element was celebrated in the inaugural show featuring Zhang Ding (all works 2019). “High-Speed Forms” was an all-encompassing interactive installation of a twisty route of steel motorway barriers snaking into an abyss. The intoxicating experience, meant to be viewed as one entity, entailed a smooth road negotiated by an audience seated in computer-controlled wheelchairs. The effect was part slot car racetrack, and part fairground ghost train, complete with luminous green skeletons on giclée print lining the route, titled High-Speed Forms #7, #8, and #9. Zhang labels these as “the body driving within itself,” referring to society as a whole.

A car seat mounted on a pillar at the entrance, High-Speed Forms #4, was surmounted by a gilded sculpture of copulating rhinoceros, alluding to the “gray rhino,” pertaining to neglected threats with high probability and impact. Gilded too were the limousines seen in photographs that decorated the walls, in High-Speed Forms #6 and #10. Along the exhibition’s artificial roadside, panoramic video screens―High-Speed Forms #3―repeated sequences of zooming vanishing points and converging lanes. Complementing these emblems of power, flamboyance, and a high-octane lifestyle, Zhang made vehement claims for the work’s effects. In the show’s accompanying booklet in discussing the trackside images, he says they “forcefully purge the body out of the speeding vehicle or brutally insert speed . . . in a pseudo-cyborg fashion.” However, while hairpin bends, strobing lights, and cacophony, in the sound and light installation High-Speed Forms #2―as if a Grand Prix race was just next-door―evoked reckless velocity, the actual vehicles trundled slowly, guided by an unseen hand in stuttering automated movement. When fewer visitors appeared, the chairs, like phantoms, drove on without occupants.

Zhang, wearing dark glasses, and with practiced coolness, evoked the work’s antecedents in an introductory video by the entrance, proclaiming, “I like driving at night.” His words resonate with those of pioneering minimalist sculptor Tony Smith, whose poetic description of a drive on the unlit and unfinished New Jersey Turnpike, during a 1966 interview with Artforum, defined an attitude that expanded the possibilities of sculpture. Veering off the main road, Smith took his students through the raw landscape of civil engineering, an event he deemed as a new type of cultural locomotion. Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, and Stephen Izenour echo Smith’s account in their book Learning from Las Vegas (1972), in which they dissect the city’s architecture as reactive to the perceptions of people zooming past in an automobile. For Zhang, like the artists and critics of the 1960s and ’70s, automated movement gives access to an authentic contemporary experience that eludes the static spectator. The drive cannot be broken down into moments with time for reflection; it can only be experienced as change.

Zhang’s overall purpose for the grandiloquent work remains ambiguous, although there were clues. In the exhibition booklet, he writes of “crisis,” but offers no context or details. Correspondingly, the installation featured a substantial amount of small, nearly illegible text on the walls―a 1922 poem by Russian poet Osip Mandelstam. Conventionally titled The Age, the piece reviews Mandelstam’s time in terms of corporal harm, and was rendered by Zhang as “The Century.” Presumably this was a reference to French philosopher Alain Badiou’s titular book that considers the poem in relation to the epoch from the Russian Revolution to the collapse of communism in the country. Badiou addresses the poem as expressive of Soviet people’s nostalgia, forgetting the brutalities of their capitalism-ravished past.

In this context then, does Zhang’s route represent an autocratic system? Do the roadside billboards, determining what is seen, project dynamic progress and improvement? Or, are fools being willingly sucked into an absurd path of fallacious promises; emancipation from the shackles of ponderous robotic wheelchairs, and access to a life of blingy fast cars? Whichever perspective they embrace, participants of Zhang’s project are deposited back where they started, with the possibility to resolve such duality and restore harmony by slowly taking another turn round the circuit.

Zhang Ding’s “High-Speed Forms” is on view at OCAT Shanghai until April 3, 2020.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.