-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of HO SIN TUNG’s “Icarus Shrugged” at Hanart TZ Gallery, Hong Kong, 2015. Photo by Kitmin Lee. Courtesy Hanart TZ Gallery.

HO SIN TUNG, UA Whampoa, 6th August 1993 (detail), 2015, color pencil and acrylic on paper mounted on board, set of six: 102 × 68 cm each. Courtesy Hanart TZ Gallery, Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s Hanart TZ Gallery is currently hosting a dual solo exhibition of Ho Sin Tung and Agi Chen Yi-Chieh, two emerging artists from Hong Kong and Taiwan, respectively. Ho’s show, entitled “Icarus Shrugged," presents a collection of seven intricate works across a variety of media, including video installation, drawing, ink and acrylic on paper. Her latest artworks trace the depths of human desire through a cast of fictional characters spun from her imagination. In addition, Chen’s exhibition “Encoded Islands” brings together a colorful pyrotechnic display of pop-culture mania. Featuring collagist imagery that reflect on contemporary mass-media aesthetics, Chen showcases a series of five works produced during the last ten years.

Ho Sin Tung: “Icarus Shrugged”

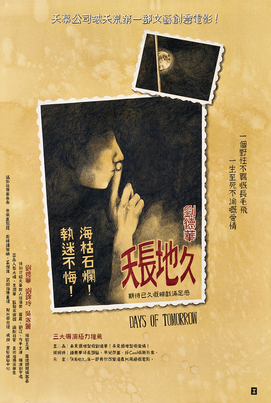

For her most recent works, Ho collates textual references by connecting decades of cultural paraphernalia—from movie posters of the 1993 film Jurassic Park to a display of 33 various editions of the book cover for the novel The End of the Affair (1951) by Graham Greene.

In UA Whampoa, 6th August 1993 (2015), Ho re-envisions an incident of attempted murder that transpired in Hong Kong in the summer of 1993. A 22-year-old serial killer named Lam Kwok-wai, who had intended to pursue his rape victim by setting up a date with her at a movie theatre, was arrested at the scene by undercover police officers. After researching the case, Ho decided to draw a set of six different posters illustrating the films that were screening that night at the UA Whampoa cinema in Kowloon. Created with color pencil and acrylic on paper, Ho conceals and erases key elements of the posters to reveal an encounter that could have unfolded into another one of Lam’s ghastly murders. Twisting a true story of crime into her own narrative framework, Ho’s selective censorship beckons viewers to reimagine the event, and think about which film the murderer and victim may have ultimately watched if they had made it into the theatre.

The display of Ho’s works also includes a more thoroughly abstract set of works, entitled “Miss Dong Quartet” (2014–15). In her artist statement, the artist reveals that she was inspired by the Greek myth of Icarus and his tragic demise upon attempting to escape from the Labyrinth. Ho communicates these ideas of the Labyrinth in her drawings, which depict unfortunate characters trapped in their own self-constructed worlds and their inability to connect with the people they long for. One of the drawings, Miss Dong Quartet: Miss Tung (Tung) (2014), depicts a mysterious, tripedal woman balancing on her hands with her legs arched over her head like a three-tailed scorpion. Wide-eyed and perplexed, a horse adjacent to her sits on its back ensnared by a bundle of fairy lights. Below this imagery, within the same drawing, a transcription of Song Dongye’s folk song Miss Dong (2012) is written verbatim in both English and Chinese.

Agi Chen Yi-Chieh: “Encoded Islands”

The overwhelming cultural kleptomania in Agi Chen Yi-Chieh’s work comes in bathetic contrast to Ho’s installations. Chen’s cryptic chaos manifests in a Superflat veneration, riding the Neo-Pop wave that brought Takashi Murakami’s Japanese kitsch to international spotlight during the 2000s. Her Circle Island (2012) plugs perfectly into the world of “Cool Japan,” constructing allegories by the dozen that salute the insulated otaku subculture of Japanese geekdom. The four-meter-wide diasec-mounted digital print is an explosive inundation of concentric circles, an assortment of colors that draws references from the realms of Japanese anime and American cartoon icons. Here, Chen takes the concept of marketing this “imported” art style to the West quite literally—hauling in everything from the cesspool of consumerism into one gargantuan, digital-art print.

Presented in a Minimalist format, Chen appropriates popular visual media from her childhood as a communicative element that, according to her exhibition statement, draws on society’s “collective visual memories.” Circle Island results in a razzmatazz of giddy youth culture dotted with visual connections to the popular video game Mario Bros., the Japanse anime series One Piece, the animated movie Kiki’s Delivery Service and a cast of other well-known cartoon personalities. This pop-culture pandering is her form of allegorical expression—best described by art critic Craig Owens as a function that “does not invent images but confiscates them,” laying “claim to the culturally significant, [and posing] as interpreter” by reconfiguring the original meaning and supplanting “an anecdotal one” as a mere “supplement.”

Chen’s syncretic play of pop culture engages viewers with her decade-long research on the subconscious function of color, and gestures at the deification of mainstream animated characters and how their representative “color codes” trigger a far-reaching effect on our minds. This somewhat overly ambitious project on memory fragmentation is not so much an “identification system,” but a collaged spectacle of clip-art JPEGs. Still, it is fair to say that Chen’s rainbow scenario can be seen as a distinct graphic language of sorts. Perhaps the historical legacy and lingering influences of Japan’s colonial rule in Taiwan have percolated profoundly into Chen’s Superflat aesthetics. If this is also a question of “cultural proximity,” in terms of Taiwan’s cultural consumption and Japan’s transnational power, then Chen’s creative output reflects that there is no avoiding the deep cultural resonance forged under these historic ties.

“Ho Sin Tung x Agi Chen: Duo Solo Exhibition” is on view at Hanart TZ Gallery, Hong Kong, until August 13, 2015.