-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

Installation view of “Holy Mosses,” at Blindspot Gallery, Hong Kong, 2019–20. All images courtesy the artists and Blindspot Gallery, Hong Kong.

In 2008, blogger Jenna Karvunidis’s “gender reveal” party for her unborn daughter went viral, kicking off a now common social media trend. Even before birth, biological sex becomes a primary factor of how others perceive a person. More than a decade later, a different spectacle of gender unfolded at “Holy Mosses,” curated by Nick Yu at Blindspot Gallery.

At the back of the gallery, hung from a black rail on the center of a large white wall, red velvet curtains frame a monitor showing a lounging figure wearing a shining white wig, heavy makeup, and large silicone breasts in a transparent glitter bikini. They are artist and drag performer Victoria Sin, staring back at us as they languidly narrate our automatic scrutiny of feminized bodies: “Look at her. Look at the way that she’s laying there . . .” Another video depicts a close-up of Sin’s gnashing mouth with a voiceover repeating, “I am not a woman.” Through these works, Sin pulls the curtain on the endless performance of gender, beginning at birth and, if one is objectified through art, extending past death.

Wong Wai Yin also appropriates gendered imagery in three sets of watercolors depicting figures from cheery 1950s-style advertising. Contrasting with the bright colors are the alienating taglines rendered in dated typography, which obscure the figures’ faces: “No one to talk to,” reads the text over two pairs of women’s heads leaning together mid-gossip. Wong’s posters highlight the existential anxiety of men and women who heed the calls of advertisements to strive for gendered, consumer-capitalist ideals, emphasizing the prescriptive desires underlying such commercial messages.

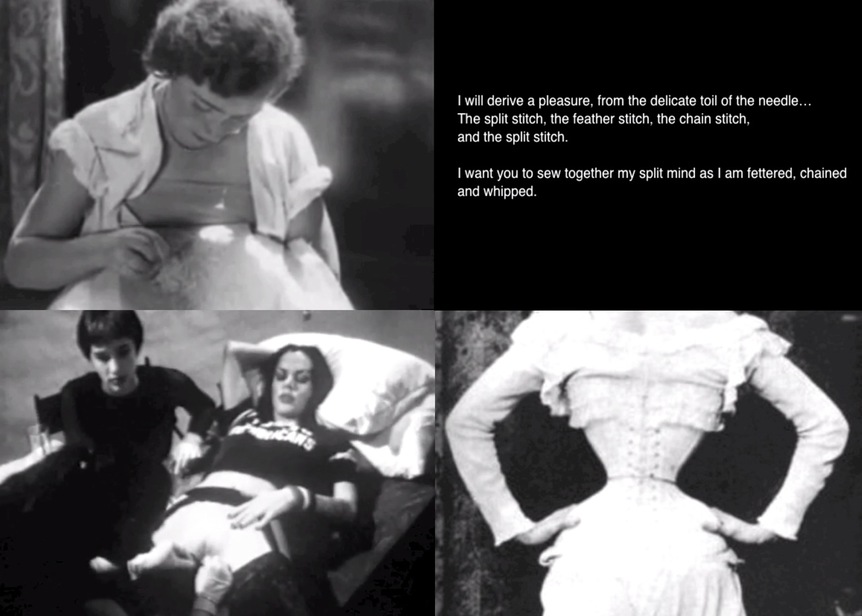

Similarly tackling mid-20th century expressions of gender norms, Angela Su’s video The Sewing Machine (2016) combines both staged and documentary footage of women working in sweatshops, as well as of performance artist Kembra Pfahler having her vagina sewn shut in 1991, all to the tune of the eponymous 1947 song in which the protagonist laments how the machine (“a girl’s best friend”) traps her in a cycle of underpaid labor. Juxtaposed with sewn-hair excerpts of 16th century French poems that simultaneously objectify and revile women’s bodies, Su tackles the interwoven expectations for women to be both sexual objects and productive laborers.

Elsewhere, WangShui’s video From Its Mouth Came a River of High-End Residential Appliances (2017–18) relates to feng shui—the ancient Chinese practice of achieving harmonious balance between built structures and their surroundings—as a symbol of ideological resistance (feng-shui practitioners in China were persecuted during the Cultural Revolution). The cool-toned drone’s-eye-view recording through Hong Kong’s “dragon gates” (feng shui-inspired, architecturally useless holes in luxury high-rises) is coupled with the artist’s voiceover linking feng shui’s emphasis on emptiness and absence with limitations of the body, of gender, and of ethnicity, creating a mesmerizing sensation of being pulled into the voids. The narrator laments a disassociation with the term “male,” outlining their true desires: “What I do want to know . . . is how to push beyond flawed accountabilities, beyond suspiciously stable identities.” Refusing definition amid current mainstream LGBTQ+ pride, WangShui proposes boundless forms instead of fixed monikers.

In keeping with the film’s call to configure bodies beyond gender, Pixy Liao’s Experimental Relationship (2007– ), a series of photographic self-portraits with her male partner, Moro, casually reverses the cliché of woman as muse. Liao instead invites Moro to wear her clothes, pose nude for her, and, in one photo, act as a human table from which Liao eats a papaya. Shot in warm daylight in domestic spaces, her images deftly pair a declaration of her agency with the lightness and ease of two lovers sharing an inside joke.

Other works on view gesture at non-human organisms’ ungendered existences. Wing Po So illuminates algae at a cellular level with reversal film in glass structures, bringing visitors back to the exhibition’s title: moss, like algae, breeds not only through sexual reproduction but also asexually, on its own. “Holy Mosses” was an emboldened challenge to binaries, the reveal being that gender can be as yet, or always, undetermined.

“Holy Mosses” is on view at Blindspot Gallery, Hong Kong, until January 18, 2020.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.