-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

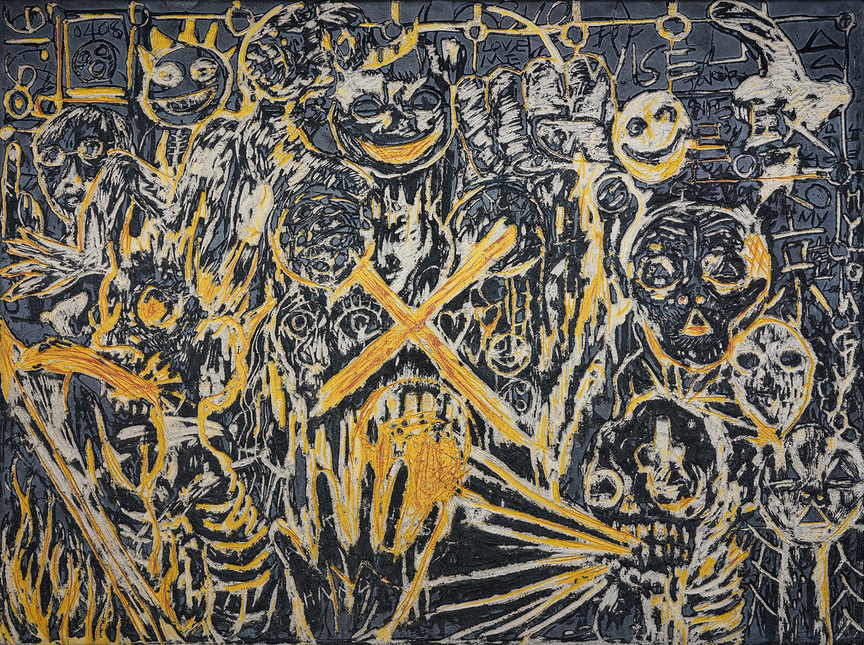

Installation view of HYON GYON’s solo exhibition at Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art, London, 2019. Photo by Benjamin Westoby. Courtesy Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art.

Occasionally, an artist who works on the very edge of experience comes along. They will paint, sculpt or create in such a way that burns holes in the fabric of propriety that veils most of everyday life, and permit us a fleeting glimpse of raw emotional substance. As many of the works in her exhibition at London’s Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art attest, at her best, Hyon Gyon is one such artist.

Undoubtedly the most striking of the works on view was We Were Ugly (2017), a mixed media work that stretches over 20 meters in width and comprises 17 wooden panels. Across the work’s sprawling surface, patches of Styrofoam have been burned away and filled with paint so vivid and shocking it evokes the acrid smoke that this process would have created. Many of the burned holes form the eyes of crudely painted skulls, screaming out from the bottom of the painting, and bold impasto streaks give the impression of bodies—both with and without flesh—amid flames, in reference to the legacy of past violent conflicts in Korea, China and Japan, most notably the dropping of atomic bombs by the United States on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Installation view of HYON GYON’s We Were Ugly, 2017, oil and mixed media on fabrics, Styrofoam and wooden panel, 240 × 2,040 × 12.7 cm, at her solo exhibition, Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art, London, 2019. Photo by Dhiyandra Natalegawa. Courtesy the artist.

In other paintings, such as Flame (2010) and Hello Another Me (2011), there is no less raw power, but considerably more detail. Central to the former work are three cartoonish stuffed animals burning on a pyre. Rainbows shoot forth from tears in their bodies, pooling with the remarkably elaborate fire below them, and a no less detailed mass of black hair that cascades from the top of the painting. The hellish flames lick at a series of small female figures painted against meticulously patterned backgrounds. Several of them are heavily sexualized, while others hang from nooses and one cradles an infant. With such imagery, Hyon Gyon lays bare the psychological burden of the many roles foisted upon women in patriarchal societies.

The bawdy garishness in some of these works tread a fine line. With their clashing colours and forms, unsubtle emotion and outright grotesqueness, they have many of the tropes for which contemporary art is often mocked. However, they are infused with a sincerity and trace of the artist’s hand that makes them compelling. In some of the sculptural works, such as Dear Beloved (2018), this “hand” is literal. A crude mosaic bust of a wide-mouthed figure sits on a plinth, which bears handprints, and the scratched words: “Beloved, don’t believe every spirit, but test the spirits”—a quote from the bible. Although little explanation is provided—as was the case for many of the works at the show—this is one of Hyon Gyon’s subtler and therefore more effective uses of text. Elsewhere, it risks coming across as maudlin, even adolescent. In A Chain of Struggles (2018), for instance, the branches of a steel-spined tree present boxing gloves painted with messages such as “Life is shit and then you die.”

In fact, Hyon Gyon’s artistic language is so intuitively sophisticated, so subtly aware of an overall sense of harmony despite its discordant elements, and so pure in its apparent crudeness, that the introduction of written language, for the most part, detracts from its power. A sculpture such as The Last Man (2017), whose lumpy arms and erect penis are formed from stockings containing stuffed animals, is disturbing and potent enough without any assistance or explanation.

In the upstairs room of the gallery there were, however, some relatively more subtle works. Made with sgraffito—a technique in which the artist scratches through a top layer of lime mortar to reveal a painted surface below—Inner Voice and You Weren’t Supposed to See (both 2018) show, in messy clusters of faces and figures using fewer and slightly more muted colors, that Hyon Gyon is as capable of accessing the visceral with a minimal approach as she is with the drastic, explosive combinations of color and materials she employs elsewhere. No matter the method, underneath it all she shows that same raw, emotional substance.

Ned Carter Miles is ArtAsiaPacific’s London desk editor.

Hyon Gyon’s solo exhibition is on view at the Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art, London, until March 31, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.