-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

DIA AL-AZZAWI, Five Children Playing Football, 2015–16, ink on paper mounted on canvas, 3 × 10 m. Courtesy Qatar Museums.

On October 17, 2016, as Iraqi-born, London-based Dia al-Azzawi spoke to visitors at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, a trickle of incoming messages shifted the audience’s attention to their smartphones. News of the Iraq-led military campaign to retake Mosul from the self-described Islamic State was breaking online. Septuagenarian al-Azzawi, a native of Iraq who has resided in London since 1976, would be notified later of yet another painful episode in the history of his home country.

At the time, al-Azzawi was giving a talk with curator Catherine David that accompanied his retrospective, “I Am the Cry, Who Will Give Voice to Me?,” which exhibited over 400 works at both QM Gallery Al Riwaq and Mathaf, including paintings, drawings, sculptures and artist book. The duo locations represented two paths of the artist’s practice—the display at QM Gallery embodied his political candor and that at Mathaf showed his love for the written word and mythology.

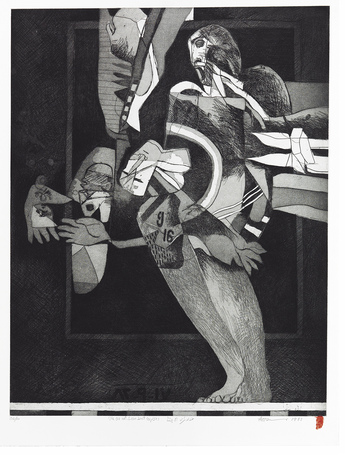

Unsurprisingly, the mural-sized ink-and-crayon drawing Sabra and Shatila Massacre (1982–83)—whose inclusion in the Tate Modern’s permanent collection is a point of pride among the Middle Eastern art world—was lavished with attention by visitors, as was evident in its prominent display, which eclipsed the debut of another drawing entitled Five Children Playing Football (2015–16). The placement of Five Children in a passageway connecting two rooms made it easy to overlook, but the three-by-ten-meter artwork still left a few visitors in awe on opening night as they absorbed the blocks of black and ochre. In the work, two-thirds of its imagery is a mess of abstract forms from which limbs and featureless faces protrude; from the right, three long objects with sharp ends—bayoneted rifles, perhaps—point toward them. A laced boot and muscled calves suggest that soldiers are behind this aggression. The drawing, as the artist stated, depicts the Israeli military’s repeated targeting of Gazan children, and the dread of conflict is palpable even in an abstracted depiction.

Al-Azzawi has long had Palestine on his mind, and has created several large works based on the country’s 68-year discord with Israel. In his triptych painting Jenin (2002), each panel depicts a keffiyeh-donning feminine figure in various postures, who shares the canvas with olive leaves and a dove. Unlike Sabra and Shatila or Five Children, the background in Jenin is sparse; a single figure is the sole focus in each frame. In the left panel, her eyes are closed; as she opens them in the center and right canvases, they are depicted as blank, wide and hollow. She is expressionless across the sequence, which shows her being thrown backward by an explosive blast that has kicked up a black cloud behind her. In otherwise monochromatic panels, al-Azzawi leaves a red handprint over his signature on each: a pointed reminder of the Battle of Jenin in the West Bank in 2002, the casualties of which became the inspiration for this very work.

If Al Riwaq’s portion of the retrospective captured al-Azzawi’s perception of troubling events, then the artworks at Mathaf reflected his thoughtful consideration of Arab identity through literature and history. His painting Dream of an Egyptian Princess (1995) sat within a gilded frame adorned with hieroglyphics and Arabic script, mirroring Cairene mosques’ building blocks, some of which were cut from ancient Egyptian monuments. In the painting, as in Jenin, black hollow eyes are depicted on two human figures standing like monuments before a solid, black background. Their ocular feature is one that is commonly found in Sumerian votive statues, which al-Azzawi encountered frequently when he was an archeologist in Iraq during the 1960s and ’70s. Across his artwork, we see a search for the shared roots that bind together those living in diverse lands that are often assigned a single, catchall label tinged with preconceptions—the “Middle East.”

“I Am the Cry, Who Will Give Voice to Me?” is a line taken from a poem—a painful clarion call—by Iraqi writer Fadhil al-Azzawi. David’s curation covered an incredibly vast scope of al-Azzawi’s artistic progression, one that was overwhelming by virtue of the cornucopia of artwork and information packed into both locales. From room to room, one observed different facets of al-Azzawi’s identity—former soldier, archeologist, voracious reader, creator and exile—and the identities of others he paints. Al-Azzawi is an odd beast, a being of restless energy that taps into timeless legends and unfolding histories to give voice to those who share his blood, bonds and battles.

Dia al-Azzawi’s “I Am the Cry, Who Will Give Voice to Me?” is on view at QM Gallery Al Riwaq and Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, until April 16, 2017.

Brady Ng is reviews editor at ArtAsiaPacific.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.