-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

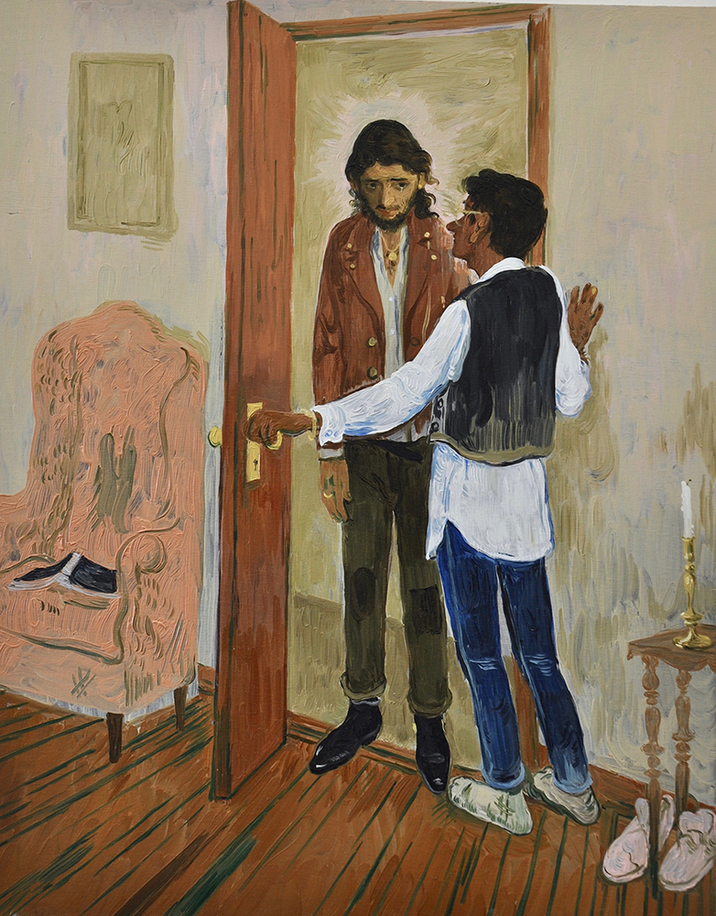

Installation view of SALMAN TOOR’s solo exhibition “I Know a Place,” at Nature Morte, New Delhi, 2019–20. All images courtesy the artist and Nature Morte.

Figurative painter Salman Toor’s protagonists are typically young, urban, queer men of South Asian lineage, with characteristically slight builds and tenaciously performed gaiety. “I Know a Place,” the Lahore-born, New York-based artist’s first solo exhibition in India, featured 17 recent paintings that give us startling access into the lives of Toor’s subjects, sensitively portrayed in scenarios that by turns imply vulnerability, intimacy, and the celebration of hard-won liberties.

Opening the exhibition was Mehfil/Party (all works 2019), depicting a small audience watching a musical performance in a baithak, a parlor with informal floor seating around the musicians. In the center of the canvas are two young men absorbed in conversation, turned away from the spectator as well as the other figures who populate the scene. The composition trains one’s gaze on the pair’s all-consuming delight in one another, casting the viewer as a voyeur. There is undoubtedly a sense of exoticism in the way the scene is set, which recalls 19th-century Western Orientalist paintings. Mehfil/Party thus exemplifies Toor’s strategy of appropriating elements of the classical Western art-historical canon as a means of asserting the postcolonial right for self-representation.

Likewise, Man with Limp Wrist illustrates Toor’s stated desire to paint like the “white Old Masters.” In this painting, a skinny, naked figure with a distended belly and disproportionately large hands and feet stands amid a plain haloed background. The man has an unruly head of black hair with an endearing flyaway curl, and a wispy mustache on his youthful face. The elongated body and downcast eyes bring to mind Parmigianino’s Madonna with the Long Neck (c. 1535–40). The realistic rendering using perspective and chiaroscuro, and the luminous lighting, all meticulously painted in thick strokes of oil, showcase Western techniques that are not part of South Asian miniature painting traditions.

Crafted from a mix of memory and imagination, Toor’s scenes chronicle chance meetings and passionate embraces but also moments of sadness and fear. Funeral, for instance, conveys the loneliness of a young boy standing amid a group of seated men. The child’s isolation is emphasized by his orange shirt and the pool of light surrounding him, in contrast to the adults painted in shadow. All is not joyful in Arrival II as a dejected man, perhaps in the aftermath of a broken relationship, arrives at the door of his friend. Helplessness pervades Ambush II, where two young men are stopped in their car by policemen on a deserted road, as well as The Beating, where a man with a horrified expression is violently attacked outside a house by a stick-wielding bully as three men look on. The aggressors and victims are both ostensibly Brown, locating Toor’s explorations of masculinity and violence in the context of South Asia’s still largely conservative, patriarchal, and homophobic context, as opposed to Toor’s adopted home of New York.

Toor’s subjects rejoice in this freedom throughout paintings of lunch dates and parties. In Late Night Gathering, a man and woman gaze fondly back at the other guests as they exit the room through a narrow door on the left side of the canvas, and three men are engaged in conversation on the right. The middle ground in the center of the painting is occupied by a man seated on a green armchair, delicately twirling a martini glass in his left hand and holding a lit cigarette in his right. He gazes at the screen of the phone held in front of his face by a man leaning tenderly over him. Another man, wearing only pink boxers, lies sleeping on a sofa. The tableau has a casual and naturalistic air. Here, Toor’s protagonists exist comfortably in their own world, without acknowledging or needing validation from the spectator. Depicting non-normative characters with full, complex lives, Toor’s paintings act as an affirmation of his queer, diasporic community.

Salman Toor’s “I Know a Place” was on view at Nature Morte, New Delhi, from December 9, 2019, until January 4, 2020.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.